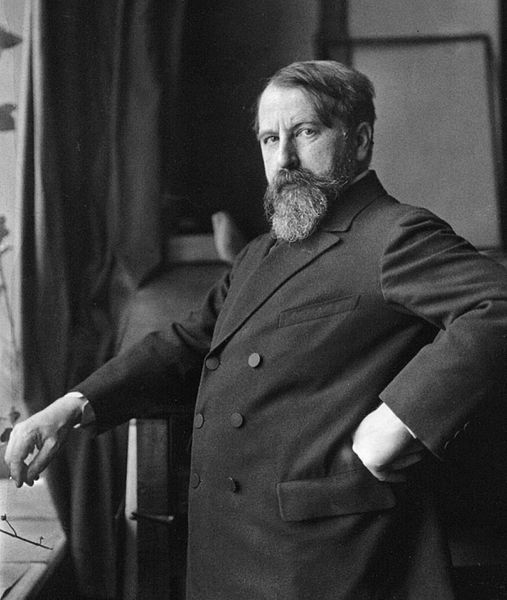

Henry James is one of those authors who it is far more enjoyable to think about reading than actually to read. His reputation precedes him. He is perhaps the greatest sentence writer in the history of the English language. His novels are subtle explorations of the differences between the Old World and the New, and filled with moral murkiness. Who is not attracted by such a description? For anyone interested in writing, how can you justify not studying the sentences of a master?

When you actually read Henry James, though, it’s another story entirely. His sentences are long, and they are certainly complex. In a way, they are terribly beautiful too. But I cannot get pleasure out of reading them. In the same way, his stories, with their endless subtleties, often seem to be missing a soul to be subtle about. There are few writers who so successfully send my gaze away from the page and out towards the window.

Roderick Hudson is the story of a talented, perhaps even genius, American sculptor, the eponymous Hudson, who is taken to Europe by a wealthy patron, Rowland Mallet, to learn from the masters of that continent and their legacies. But Europe, specifically Rome, teaches young Roderick far more than simply how to sculpt brilliantly. In Europe Roderick encounters Christina Light, a young woman of great vitality and changeability, who makes a vivid contrast to the dreary Puritans of Roderick’s New England homeland. Roderick has left in America a fiancée, Mary Garland. Can there really be a danger in his acquaintance with Miss Light?

Roderick Hudson, Genius?

The character of Roderick Hudson is presented through the eyes of his friend Rowland. Though Roderick Hudson uses a narrator, he hangs behind Rowland’s eyes for the course of the novel. Where he comes in is to warn us of events to come, something which happens with some regularity. From early in the book we have a sense of coming tragedy, but what exactly will happen is left only as vague hints about future tears.

Roderick is a young man when we meet him. He is training to work in the legal profession, something one character wittily describes as “reading law, at the rate of a page a day”. The work is not for him. Rowland, who is not old himself and has plenty of money, decides, after seeing an example of Roderick’s work, to take him under his wing and go to Europe. His mother and cousin (soon, fiancée) are at first sceptical, but Rowland assures them that Roderick has real talent, and eventually they relent.

He does have real talent, and we are repeatedly told he is “genius”. But unfortunately, being a genius is not quite enough to be a great sculptor. What one also needs is discipline and hard work. Roderick, perhaps, is capable of these things. But Roderick Hudson is the record of his drifting away from them as other pleasures and other desires occlude his passion for work. For Roderick is a young man from a boring, Puritanical, New England world. It is a far cry from Rome, from unrestraint and luxury and excitement. Rowland worries, as he takes Roderick away, that perhaps he is making a mistake. The world they leave behind is one of “kindness, comfort, safety, the warning voice of duty, the perfect hush of temptation”. The one they enter turns out to be anything but.

Rowland and his Responsibility

Rowland is not a particularly forceful character. He has more money than he has ideas, and no talent whatsoever, which forces him to look to Roderick for anything like success or achievement in this world. Instead of trying to get a job, he goes to a place – Europe – where it does not matter whether he has a job or not. He falls in love with Roderick’s fiancée but spends the novel trying to prevent Roderick and Mary from breaking their engagement. He takes care of Roderick, but more financially than morally. Rowland seems to have an instinctive fear of involvement, of danger, of conflict. So he watches Roderick’s decline without stopping it. It is hard not to dislike him for this, for his unwillingness to get either his own life in order, or that of Roderick. I certainly was ambivalent towards him.

Unless you are Emily Dickinson, it is hard to be a great artist without some degree of experience, of mobility. Rowland is right to take Roderick away, to give him a chance. But he is wrong to think that Europe can only offer positive developments. At the end of the first chapter in Europe, Roderick declares he wants to go off on his own, and Rowland, who bankrolls everything, lets him. The next time we meet our hero, he’s already gravely in debt. “Experience” turns out to be women and gambling. “I possess an almost unlimited susceptibility to the influence of a beautiful woman,” Roderick declares. Rowland, who forgives his protégé everything, does not admit to himself the danger of the words. Instead, he thinks that Roderick’s engagement to his cousin, Mary Garland, is a sufficient guarantee of good behaviour. How wrong he is.

Christina Light

Christina Light is the woman who provides the danger at the heart of Roderick Hudson. She is an American, but has lived her twenty years of life on the Continent. Compared to the Puritans that Roderick leaves behind, Christina is a breath of fresh air. But even Roderick perceives, at least vaguely, that she might prove a problem. If “Beauty is immoral”, he says upon first seeing her, echoing the views of his family back home, then Christina is “the incarnation of evil”. He does not seem to realise that in the words of the New Englanders there may be more than just a grain of truth.

Christina is extremely beautiful, but capricious. Her mother tries to control her, with partial success, and Christina makes use of scandal and flirtation as her one source of freedom. Roderick appeals to her, and they begin a long will-they-or-won’t-they that runs the length of Roderick Hudson. Roderick thinks of the young woman as his Muse, but it doesn’t take long for his feelings of jealousy and frustration to turn his Muse into the opposite, and for his inspiration’s flow to run dry. Christina’s mother is obsessed with finding a rich prince for her daughter, and Roderick is neither of noble blood nor in possession of a positive balance at the bank. But he is unable to see the impossibility of the situation, or that in some way Christina might be using him for her own ends. Alas, his love leaves him blind to the truth.

A Backdrop of Stability: the Artists and Puritans of Roderick Hudson

Roderick and Christina have stormy emotions but also a great deal of vitality. Roderick Hudson, however, by its end seems to pronounce judgement on their style of living, and that judgement is not a positive one. In our search for positive characters we must look at the Puritans of the novel, and the artists of Rowland’s circle. Mary Garland, Roderick’s fiancée, is the main representative of the former group. She is intelligent, which we see by her constant reading and questioning, and she is also natural and unaffected in style. This is in contrast to Christina, who is always described as playing a role or being “dramatic”. Mary is honest too, which leaves her less vulnerable to her imagination. She faces the world, instead of trying to flee it like her fiancé.

Of the artists, a group made of Rowland’s friends in Rome, Sam Singleton stands out as a heroic figure. He is a painter of small talent, but of hard work. We know that he does not produce masterpieces, but whenever we see him, he is training, learning, and active. Instead of waiting idly for inspiration to come as does Roderick, Singleton goes out to hone his skills to be ready for it when it does. Roderick describes him as “a watch that never runs down. If one listens hard one hears you always – tic-tic, tic-tic.” We know that if Roderick had even an ounce of Singleton’s work ethic, he would be a far better sculptor, but it is also true that he would be a better person.

Singleton is happy, calm, at peace, where Roderick is prey to the full force of his emotions. A great artist is the one who can master their emotions and set them upon the page or marble, not simply experience them. Singleton’s weakness is a lack of torrential emotions, but it is an artistic weakness, not a human one. By the end of Roderick Hudson it was clear which of the two artists I would prefer to be, however boring my choice is.

Conclusion

I confess that by about the half-way point I was rather keen to get Roderick Hudson over and done with. That’s not to say that I didn’t like the book – it was thoroughly okay – but there are many other books, waiting on my shelf, which I’m quite certain I will enjoy more. By the end, reading Roderick Hudson felt like a kind of penance, a sign of deference to the Master, but certainly not an act of love or pleasure. There are various reasons for this, and in his preface James notes several of them for us.

For one, the story is rather too determined by “developments”, events that seem rather forced. The novel’s final section, in Switzerland, is particularly weak in this regard – suddenly all the characters from Rome meet again, and James simply expects us to take this on faith. When James has his characters exclaim “it’s like something in a novel” this is no excuse. In fact, this spoils the impression still further. Rather than drawing our attention to the artificiality of the structure, the structure itself ought to have been altered.

I’m also not a great fan of the characters. Perhaps the women of the late 19th century were all as flighty as Christina Light or as sombre and serious as Mary Garland, but I struggle to believe that people were that simple. Being changeable does not make for a great or believable character. And beauty is not a character trait – it is laziness. The men come off only slightly better, but overall, I found myself disliking most of the characters, which made it hard to care about any of them or their fates. Rowland is ineffectual; Roderick is just an idiot.

Roderick Hudson was James’s first serious novel. Though he revised it later, it still bears the marks of his youth. Whatever technical genius he already displays here – and there are some awe-inspiring sentences – his feeling for people still has a way to go. I had planned to read all of James’s novels one-after-another as a kind of project. Unfortunately, for now I feel like I’d rather just think about reading them all instead.