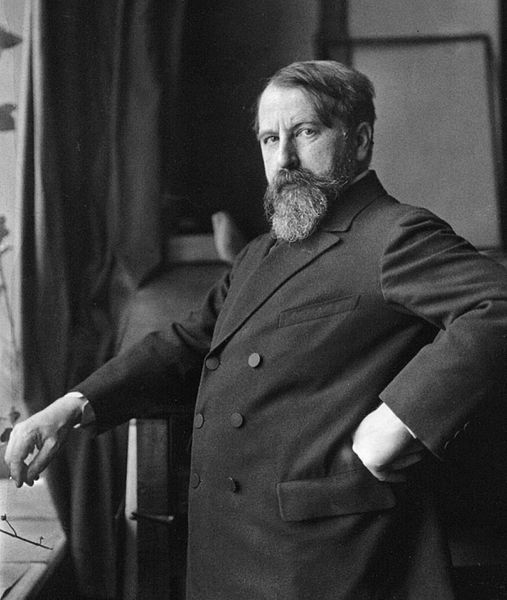

Fräulein Else is a surprising novella of sex and desire that retains its power to shock even now, almost a hundred years after it was published in 1924. Its Austrian-Jewish author, Arthur Schnitzler, was rather notorious in his day for his works’ frank depictions of sexuality, especially – in the case of Fräulein Else – of female sexuality. Taking us inside his characters’ heads, in a stream of consciousness style reminiscent of Molly Bloom’s in Ulysses, Schnitzler in Fräulein Else and elsewhere shows us what, under the respectable veneer of 19th century literary realism, was lurking all along – real and violent passion.

Fräulein Else is the story of a young girl whose life falls apart over the course of one evening. A playful and young nature comes against forces she is unable to withstand – forces of power, both masculine and monetary. Else’s story is that of an attempt to live against a world that is unwilling to let her do so, and the results are ultimately fatal.

Setting the Scene – the beginning of Fräulein Else

We are introduced in Fräulein Else to our protagonist in her natural state – at play. She has just finished a round of tennis with her cousin and his lover and she has decided to go back to her hotel. Else is in Italy, in the Trentino resort of San Martino di Castrozza. Whether the action takes place before or after the First World War is hard to make out – the hotel is full of international guests, just as in a Henry James novel – but we have a sense that for the likes of Else, the time doesn’t matter. She plays games, flirts endlessly in her head, imagines herself with many lovers, pictures a wonderful villa by the beach, and obsesses over her naked figure. All is well in the world.

But then a letter comes from home in Vienna. Her father, a lawyer, has fallen on hard times and there is no way for the family to keep itself afloat without Else’s help. Every friend has already lent him money, and there is now no choice but for Else to ask an acquaintance of her father’s at the hotel, Herr Dorsday, whether he would pay off the 30000 Guilder debt within the next two days. Otherwise the debtors’ prison awaits him. Else eventually asks Dorsday for her help, but he sets a condition – Else must show herself to him, naked, at midnight. After all her sexual imaginings, the idea repulses her, and she is sent spiralling into confusion. On the one hand, the demands of her father, of maintaining her social position; on the other, her desire for sexual autonomy.

One moment she seems to condemn her father to either shooting himself or being locked up; the next, she wants it to be herself who dies.

Else herself – a successful free spirit?

Coming from the 19th century as I more or less do, Else’s clearly articulated sexuality is surprising, if not quite as shocking as it would once have been. Her pleasure in her young and naked body shows the pure desire to live that she embodies:

“Ah, how wonderful it is to walk naked up and down one’s room. Am I really as beautiful as the mirror makes me look? Ah, come a little closer, my young lady. I want to kiss your blood-red lips. I want to press your breasts to mine. What a shame it is, that glass, cold glass, separates the two of us. Oh how good we would be together. Isn’t it so? We need nobody else. Not a single other human being.”

But for all her sexual confidence, the text also reveals a kind of solipsism on Else’s part. Without any love for those in the world, she ultimately turns inward. She is free spirited, imagining herself with hundreds of lovers, but she has no respect for any of them. I liked her because of her wilfulness, not because she is in any way a good person. But this lack of love for others is also, it seems, the result of a lack of love from them too. After dismissing the French and piano lessons she concludes of her upbringing: “But what goes on in my heart and what digs at me and makes me afraid, has anyone ever cared about that?” We have a sense that, even disregarding the stream of consciousness, Else is not only unhappy, she is also terribly alone.

A Woman’s Lot

Thoughts of suicide circle around Else like flies. She has several capsules of Veronal, a popular sleeping pill, and even before the letter arrives she considers taking them all. For all her spiritedness, what stands out about Else is just how unhappy she is. In spite of her attempts to maintain autonomy in this world, it’s clear that she’s trapped in it. Even though she pretends that all is well at the novel’s beginning, the very fact that she has the pills on hand suggests that this is not exactly the case.

She is not talented. She admits as much. “I’m not made for a bourgeois life. I possess no talent”. She speaks several languages and plays the piano, but in the end, there’s nothing she can do with her life except waft about hotels. Her choice is either a sensible marriage, or a “nurse or telephone operator”. For a woman at the time, there were few other choices. When she tries to assert herself, her only option is to be a “Luden” – a slut, as opposed to the whore Dorsday wants her to be, or a passive wife. But even this assertion is imperilled by her dependence on Dorsday’s money. In the end, she can barely assert herself at all.

Else hatches an insane plan involving going to Dorsday, who is listening to music, naked but for a coat and shoes. She is successful, but the intensity of the moment leads to her fainting and being carried back to her room by her cousin and her aunt while they wait for a doctor. Here again we have a sense of Else’s powerlessness as a woman. Her problems and mental state are immediately dismissed as hysteria and – what is more – her aunt thinks the best course of action is simply to lock Else away in an institution. Even among women, the pressure to conform is paralysing, and the punishments for non-conformity are terrifying. Else, who has shown her sexuality in public via her nakedness, now must be hidden away.

Decline and Fall: Money and Society

But the greatest pressures on Else are financial. One key tension of Fräulein Else lies between one’s place in society, and where one ought to be. As Else remarks, she’s not fit for the bourgeois life. Alongside her own thoughts of suicide, she mentions that her father’s brother killed himself when he was young too. Her father is desperately, and failingly, trying to maintain his position in society through money that he doesn’t have. Else herself can only enjoy the hotel because of the good graces of her aunt, who is paying for her stay. Wherever she looks, she is dependent on others because she has no money for herself. Dorsday can control her because he has money, and because he is an older man. Even if Else were to go against him Dorsday can dismiss her as being hysterical. She is doubly trapped.

Stream of Consciousness, Loss of Consciousness

In fact, the very form and style of Fräulein Else plays into its suggestions about female sexuality and suffocating society. Else is free – to flirt, to imagine a beautiful future – but only within her own mind. Whenever she comes into contact with external forces, whether they be a telegram from Vienna or a chance encounter with friends, she is unable to control herself – social and familial obligations suddenly take over. At the novella’s end, when Else lies dying after a sudden faint, the situation is particularly acute. She is conscious – she hears what others are saying all around her – but she is unable to get up to act or speak for herself. In dying, she has become even more fully the object, open to the control of others, than she ever was before. The sense of being locked in is only the culmination of an entire novella’s worth of powerlessness.

Conclusion

I liked Fräulein Else. Else herself, with her divided nature and conflicting loyalties, is described well – I really felt she was alive, and though I knew what was coming it was awful to watch it happening through her eyes. I really had a sense of how much she wanted to live, and yet how hard it was for her to do so in the society she lived in. But all the same, and as much as I liked the stream of consciousness style, I felt a sense of relief when I finished the story. A feeling of claustrophobia from the style suits the plot, but it’s not something I would want to see extended into a novel-length project. Fräulein Else is good because it doesn’t overstay its welcome. Any longer and we might lose our patience with our young and foolish protagonist, or the tragedy might be blunted.

Fräulein Else is the first thing I’ve read by Schnitzler and will probably not be the last – if for no other reason than my edition also contains his “Lieutenant Gustl”, and because the German was surprisingly easy to read. For more Austro-Hungarian tales of declines and falls, Hofmannsthal, Márai, and Zweig are your “friends”.

Have I completely misread Else? Why not leave a comment below?