Alfred Döblin’s The Murder of a Buttercup is a collection of short stories written by the German writer during his early career, from 1904-11, and published in English in the book Bright Magic. I read them largely because they all fall within the time period of the German paper I’m taking next year – is there any other reason to read anything? – and because unlike, say, Robert Musil’s stories of this period, the stories collected in The Murder of a Buttercup are rather more straightforward and approachable. They are, that is, stories as well as experiments, however full they are of modernist flourishes. Döblin himself is one of the better-known German modernists, albeit one whose lifetime’s work has been reduced down to a single book – Berlin Alexanderplatz – just as Ivan Goncharov in Russia or William Makepeace Thackery in Britain have been reduced to Oblomov and Vanity Fair for the casual reader.

Whether or not that seems fair in Döblin’s case I hope to venture an early answer to at the end of this review. Before then I’ll go over a few of the stories themselves, alongside their general themes. For, whether good or not, they are certainly interesting for their modernist impulses. All translations are by Damion Searls.

The Rejection of the World – “The Sailboat Ride”

The first story in The Murder of a Buttercup is the plainly titled “The Sailboat Ride” and it is itself one of the most straightforward tales here. It details a relationship between a Brazilian man, Copetta, and a woman he meets at the beach at Ostend in Belgium. Copetta is, at forty-eight, already conscious of his age. In Paris, before the story begins, he’s spent weeks in hospital, expecting to die only to ultimately recover. Far away from home, he hopes to sample European culture. But his attention is taken by a woman he meets. After seeing her three times in one day he begins to question the assumptions underlying his life. He sends her a note before destroying both his wedding ring and his pictures of his children.

When they meet, they go for a ride into the sea on a sailboat. They are wild and restless in their passion, but in time Copetta’s mood worsens. She tries to comfort him, but without success. At last a wave comes that bears him away. She is found by the authorities, drifting on the sea – Copetta’s suicide was premeditated, and he had already sent them a telegram to warn them. But the story does not end here. Now we follow the woman as she heads to Paris and tries to stave off her grief through sexual liberation. “She denied herself to no one”. But this does not bring her the deep pleasure she is after. A year later she sends a message to Ostend: “To Mr Copetta Ostend Hotel Estrada expect me tomorrow noon. Wire reply requested.”

She returns. Her mother has died in the interim, but the news has no effect on the woman. She is filled with bliss – her madness is complete. She pretends that Copetta is alive and writes him a message, then one morning she steals a rowboat and heads into the sea. There she meets “Copetta” again. From out of the waves “a dark shape” appears. He joins her on the boat, but his body is crusted with shells and ruined. He tries to ward her off with an ambiguous wave of his arm, but she does not retreat. As they are united in intoxication and pleasure, they turn young once more, and in that moment they are both at last swept under the waves.

Meanings and Themes in “The Sailboat Ride”

“The Sailboat Ride” is a good introduction to many of the general themes of The Murder of a Buttercup. First among these is a turning away from the world. In the Modernist period many artists rejected the stodgy social conditions of the environment in which they worked. Emotions and characters that otherwise would not grace the printed page now rose to prominence and without condemnation on the part of their creators. In “The Sailboat Ride” we have Copetta’s infidelity and also the open female sexuality of the woman. Döblin’s narration in The Murder of a Buttercup is at timeshighly sensual, and this story is filled with hip-on-hip contact, mussels, and other overt and covert sexually charged emotions and symbols.

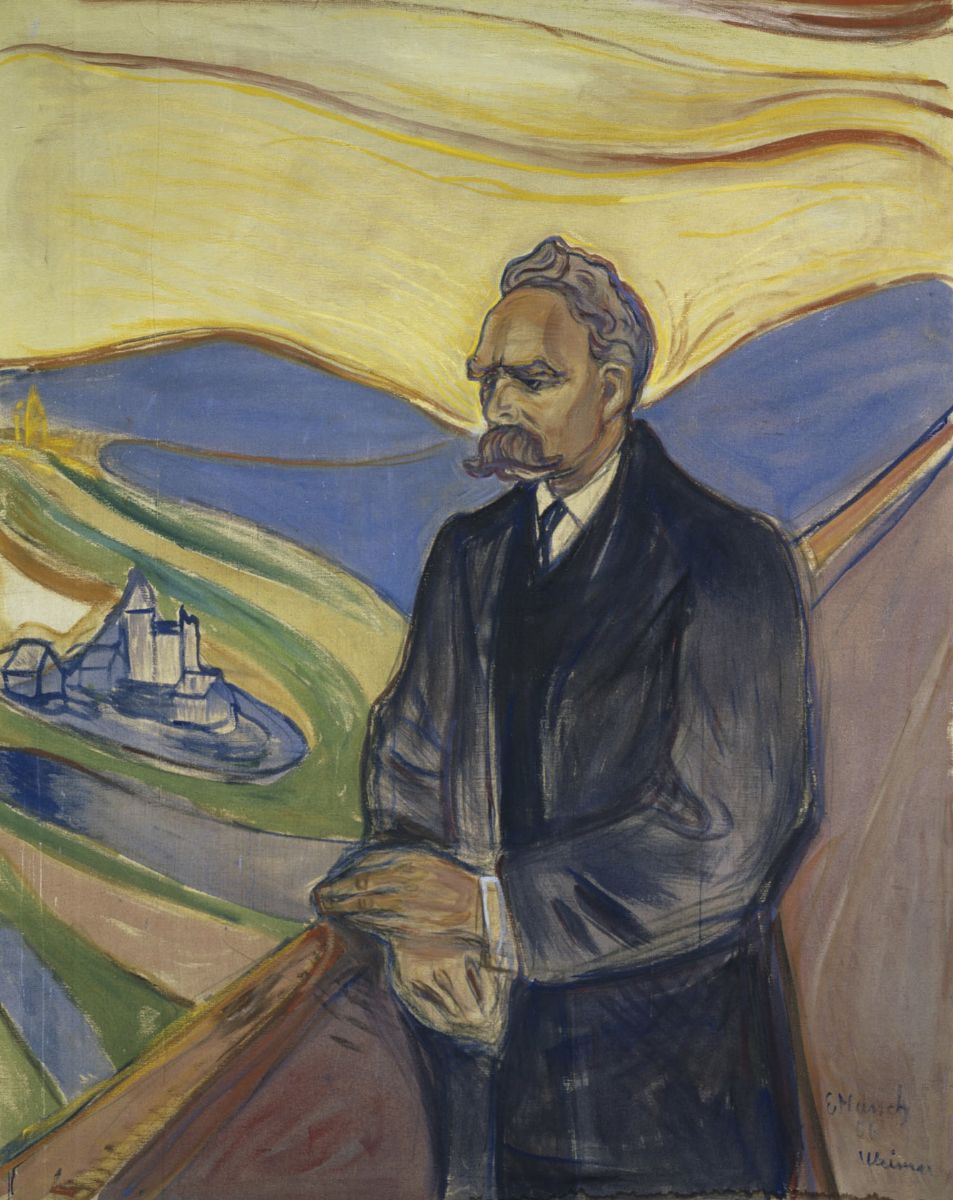

Of course, within the story both man and women are punished for their desires – Copetta’s inability to deal with socially-conditioned guilt no doubt leads to his suicide, while the woman faces condemnation for forgetting her mother and dancing with so many men. But what matters is that that at the story’s conclusion they turn their backs on society and find bliss. The sea, intoxication (a motif that directly speaks to Nietzsche’s Dionysian world in The Birth of Tragedy), allows them to come together at last, at the cost of their demise. And it’s hard to read the final moments as anything other than triumphant.

“Astralia”: Another Retreat from the World

A rejection of the world can come in many forms, and though death and suicide are common in The Murder of a Buttercup there are other retreats here. In Astralia we find a scholar, Adolf Götting, whose escape comes in the form of mysticism. As the fin-de-siècle mood in Europe worsened towards the outbreak of the First World War, and with organised religion dying, many turned to cults and mysticism to try to find a suitable faith.

The scholar of Astralia has his own mystic group, convinced that the Redeemer will soon return. They meet and drink, and drink a lot. When Götting leaves the tavern one evening he has no boots, nor hat nor coat. He thinks he is transformed into some kind of prophet, and the mockery he receives on the street only confirms his delusions. When he returns home, he treats his wife badly for not being part of his group, but when she continues to fuss about his dress and state of dishevelment he eventually breaks down: “Oh, don’t laugh…. Please, please don’t laugh. Oh, I beg you, I’m begging, beg-ging….”. The retreat fails, Götting is left a fool. Society has been too strong for him to escape.

“The Murder of a Buttercup” – Religion and Rationality

There is a tension in The Murder of a Buttercup not only between society and the self, but also between an extreme rationality and irrationality. Both Nietzsche (e.g. Beyond Good and Evil) and Max Weber (in his lecture “Science as Vocation”) warn against adopting a hyper rationalist viewpoint of the sort that was at the time coming into vogue. While on the surface science offers a lot of explanations, Nietzsche saw a wholehearted belief in science as just a continuation of the Christian world view, and as such one ultimately tending towards nihilism and a devaluation of all things. Meanwhile, Weber added that although science answers a lot of questions, nonetheless its answers are very often based on presuppositions (even today), meaning that most “facts” are nonetheless ultimately contingent. Once we start questioning what underpins them we can devalue the world that way too.

What matters, then, is to leave a little bit of irrationality in yourself instead of veering between hyper-rationalism and irrationalism. There are many characters in The Murder of a Buttercup who seem unable to do this. The most memorable on is Michael Fischer, the hero of “The Murder of a Buttercup” itself. This is an extraordinarily strange tale. On a walk in the mountains Fischer, the head of a firm in the city, attacks and dismembers a buttercup that had managed to slow him down. Fischer is a rational man, if cruel. But the murder of a buttercup is all that is necessary to lead him down the road to madness. A few moments after killing the flower he sees himself, committing the act again. A dislocation has taken place between the old Fischer and the new.

As he continues walking, guilt for the “murder” begins to eat away at him, including a fear of social repercussions – “What if someone saw him, one of his business colleagues or a lady?”. Fischer tries to control himself the same way he controls his firm. In his mind he even seems to refer to himself as a “firm”. But he is unable to win out, and images of death and decay, of the “plant corpse”, continue to eat at him. Alongside another emotion – pleasure. A kind of sexual enjoyment was to be had in murdering the plant, a “gentle lasciviousness”.

Once Fischer gets over his guilt he feels “liberated”. But back in the city this guilt returns. He finds himself crediting the buttercup money to try to buy back his peace, he makes offerings to it. He is unable to win out – he ends up crying at all the beauty in the world, beauty that his guilt is ruining. He only moves on when he takes a new buttercup home from the mountains. He lavishes attention on this one out of spite for the old one. “Never had his life passed so cheerfully” we are told. Eventually, he disappears into the forest, “laughing and snorting loudly”. His madness is complete.

Modern Anxieties in The Murder of a Buttercup

Döblin’s Berlin grew extremely rapidly in the final years of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The city and business underpin Fischer’s power and confidence. But the foundations are flimsy. There is a moment in the story where he thinks “Nobody would make a fool out of him, nobody”. Though he tries to live rationally, he gains more enjoyment from an imaginary war with a buttercup than from his entire business career. His final retreat into the forest, like Copetta and the woman’s in “The Sailboat Ride”, is a firm rejection of society and social constraints. And like theirs, it is marked by a feeling that illicit, sexual pleasures and desires and more valuable than socially constrained ones, even as those same desires have fatal consequences. Fischer’s story is also similar to “Astralia” by means of its preoccupation with religious concerns.

In “Astralia” there was an attempt to replace organised religion with a kind of mystical cult; in “The Murder of a Buttercup”, however, it is the absence of religion that is the focus. Without a god to turn to, the question of how to expiate his guilt torments Fischer incessantly and seems to be a great contributor to his eventual madness. Looking at the story through Nietzsche seems like a good approach. Guilt, of course, is a Christian emotion in Nietzsche’s view. It makes us uncomfortable acting in a way that benefits ourselves by encouraging us to think about others and external, heavenly, judgement. It is thus the hallmark of a slave-morality. Fischer lives in a godless world, but he is still hamstrung by a Christian moral system, leaving him in the double bind of feeling a bad emotion but being unable to deal with it.

He doesn’t know he is free, and that ignorance comes to destroy him.

Conclusions

There are a few other interesting stories here, including “The Wrong Door”, with its amusing play on our ideas of fate, and the coldly rational and brutally misogynistic “Memoirs of a Jaded Man”. But space and attention are at a premium and I had better wrap things up. I liked a lot of the ideas and concerns that Döblin voices in The Murder of a Buttercup. In some sense his stories, with their mix of the supernatural and irrational alongside the rational and concrete, reminded me of Borges’ work. But Borges manages in three or four pages what Döblin needs several more to do, and I’m not sure the latter’s work is better for the extra space.

It doesn’t help that his stories are rarely gripping, and there were a few times when I was left confused about what was actually happening. These aren’t instances of modernist flourishes – when Döblin’s language gets weird, it can be fantastic and beautiful – instead, these are times when he could probably simply have done with an editor. In the end, I’m left with mixed feelings. These tales are the work not of a talented author, but of someone who has everything they need to become one given time and the right circumstances. As with Isaac Babel’s Red Army Cavalry, and Platonov’s Soul and Other Stories, I can’t help but feel that the intellectual side of Döblin’s stories overpower their weaker and less gripping plots. And unfortunately, while it makes him easy to write essays about, it doesn’t really make him enjoyable to read.

But I hope his mature work, when I get around to it, will change my mind.

Have you read any Döblin? Does he get better? Leave a comment and let me know.