The Fowler Snared is a short story by the German-language writer Stefan Zweig. Though it is short, it nonetheless reflects a lot of the key preoccupations of the German “Novelle” form while putting its own spin on them. There is a tension in this short tale between our desire for power and control, and our ability to achieve that same control. As in a work of tragic drama the characters of The Fowler Snared discover that there are forces – luck, fate, whatever – that act upon them even as they try to give order to their own world.

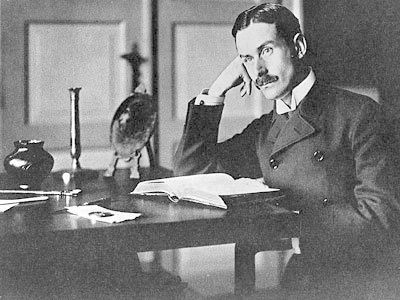

Zweig’s story, taking place on the banks of Lake Como in Northern Italy and detailing something akin to a failed romance, is typical of the highly cosmopolitan writer that Zweig was. Indeed, its setting and language reminded me somewhat of the opening of Henry James’s Daisy Miller, another work from a transnational talent. Born in Vienna 1881 to a family of wealthy but nonreligious Jews, Zweig was a pacifist and internationalist. Following Hitler’s rise to power in Germany Zweig fled first to the UK, then the United States, and finally Brazil. There, overwhelmed by Hitler’s early successes in the Second World War, he and his wife jointly committed suicide in 1942.

The Fowler Snared is from 1906 and contains none of that fear or anxiety about the world that Zweig’s later works, such as The Royal Game/Chess Story/Schachnovelle do, even though the story does acknowledge some of the darker sides of human character. But anyway, to the story.

Introduction: Plot and Form in The Fowler Snared

What’s in a story? I’ve spoken about the Novelle form in my piece on Walter Benjamin’s “The Storyteller”, and also in my thoughts on Theodor Storm’s “Aquis Submersus”. Generally we have a frame narrative, a small cast of characters, leitmotifs or recurring symbols, and a moment of crisis around the middle or else a twist. The Fowler Snared has all of these. The story begins in Cadenabbia, a place of “white villas” and “dark trees” on the banks of Lake Como. A place that is full of potential romance. But already something is slightly off, because it is August, and the narrator finds his hotel almost empty – those people looking for crowds, for adventure, would have been better off coming in the spring.

But still there are guests. The narrator singles one out, an elderly gentleman, and approaches him in search of a story. “Why, I wondered, did he not go away to some seaside resort?” the narrator asks himself. In approaching him the narrator makes us aware of the artificiality of stories, the way that they often need to be constructed out of forced experience that may often prove unrewarding. The man, however, rewards the narrator’s curiosity with a story just as he had hoped.

The Old Man’s Story: Experience and Memory

The old man, who had “never had either a fixed occupation or a fixed place of abode”, is always described in pairs of adjectives to indicate his lack of stable existence. The narrator remarks that with the end of his life his accumulated experiences would be scattered and lost. “I have no interest in memories. Experience is experienced once for all; then it is over and done with” is the man’s reply, but he agrees to tell his story all the same. And here, as we enter the second narrative layer, we first encounter the tension that will be the man’s undoing – the tension between what he says and what, ultimately, he does.

The Old Man’s Story: The Girl

A year ago the old man was staying at the same hotel, and there he came to be aware of certain guests – a family of Germans. He is intrigued by the youngest of them, a plain girl of about sixteen or seventeen. He sits watching her, unable to work out why he finds her interesting. He admits to himself that she is nothing more than a teenager, “gazing dreamily across the lake”. And already there comes a natural impulse for control – he begins to imagine her personality, where he can only see her outward appearance. “She must be dreaming”, he thinks, of romantic tales.

And so he decides to create such a tale for her and be the author of her own story – “I made up my mind to find her a lover”. He writes her a love letter without signing it, leaves it for her to find the next morning. He does not consider the risk – he has a low opinion of women and thinks the girl is much too meek and quiet to tell anybody about the letter. There is certainly a sense that the man is living out a masculine power fantasy by controlling her.

His first letter is a success and he writes another, and another. The “sport” and “game” of his “imaginary passion” brings him an immense pleasure. But it also brings the girl pleasure. She “seemed to dance as she walked”, and her previous plainness disappears now that she pays attention to her appearance. For the moment all is well, “the marionette danced, and I pulled the strings skilfully”. But our control over the world is not so permanent as the old man might have hoped.

The Old Man’s Story: Control’s Failure

There are two mistakes, two things that the old man doesn’t anticipate. In his letters, to avoid the possibility that the girl might realise it is him who is writing them, he now suggests that he comes from another resort each morning to look at her. The girl begins to sit watching the steamer. And one morning, a “handsome young fellow arrives”. Their eyes meet, and although they do not know each other they both succumb to the illusion that they were destined to meet. For the old man, this comes as a shock. “He had almost caught up with her, and I was feeling in my alarm that the edifice I had been building was about to be shattered”. At the final moment, however, the girl’s mother arrives and the two are unable to meet. But this has already revealed the fragility of the man’s overall control.

The next morning the second instance of the man’s inability to control fate is revealed. He comes across the girl in “disorder”. “The charming restlessness had been replaced by an incomprehensible misery”. He only understands when he sees that the family’s table is not laid – they have left the resort. She has been unable to meet her imagined lover. Not only that, but the man’s manipulation, which at first had brought her pleasure, is now the cause of her despair. The moral aspect of the story grows harder to avoid.

Two Moments of Conflict

The old man’s story ends. But as the narrator points out, this is not a good story. The novella form itself demands neatness, a tying up that is absent here. “A story needs an ending”, he says. And so he himself takes a more active role again, asking questions and leading the conversation. He says how he imagines the story ends: the old man was incapable of feigning passion like that forever. In the end, the passion became real. He came back to the same place a year later, hoping to find the girl and declare his love.

And here the man interrupts him with a denial that is as good as a confession. A novella often has a moment of crisis as its high point. This crisis, where the old man’s secret is revealed, is two-parted. There is of course the revelation of his secret, but more importantly there is also his failure. The girl is not here. He returned, “wooing fortune’s favour only to find fortune pitiless”. In a sense, the crisis has already taken place before the story begins. And that makes its impact, the sense of the old man’s powerlessness before fate, all the greater. He tried to control the girl, only to find another force, a more powerful force, controlling him. It is a pleasant irony and gives a nice symmetry to the story.

Stories and the Language of Control

I read The Fowler Snared in an English translation by Eden and Cedar Paul, and the translation seems to be a fine one. It didn’t get in the way of the story, and most importantly it was clear, letting the uncertainties of Zweig’s own dialogues and descriptions come to the forefront. For after all, alongside the controlling impulse of the man himself towards the girl, the act of speaking and telling a story is also one that involves giving order and control to something that is essentially boundless and untransferable – personal experience.

First, we have story itself. It is created when the narrator approaches the old man at the beginning of The Fowler Snared, then is given an ending when the narrator pressures the old man to explain his return to the resort. Even the old man himself is aware of the ways that stories are constructed. “The old fellows… would rather talk of their successes than of their failures”. He makes us aware of the inevitable gap between what we hear and what could be said. He was comfortable ending the story without acknowledging that although he had successfully manipulated the girl, he had failed to meet her this time. In the same way, it’s hard to avoid considering that the girl herself never gets a chance to speak in The Fowler Snared. Language and form control her throughout. Even the letter itself is language, weaponised as a tool for power.

Stories are a way of controlling the past. The old man, so long as he himself is speaking, is calm. But when the narrator guesses his secret, he is forced to shout over him and deny the truth. Once he has taken control again, to finish the story, he once again tries to control what we as readers learn. He quotes Balzac to describe his predicament, distancing himself by means of literature from his reality. But ultimately we are left with the knowledge that language is a double-edged sword. The very language he uses to avoid his fate is the language that got him into it. The passionate letters lead to his own ruin just as much as they lead to the girl’s.

Conclusion

I really liked The Fowler Snared. Though it is short, I felt that the way it combined its form and content was interesting. As with many novellas it presents the conflict between order and disorder, but here it shows how we humans are responsible for creating both sides of that coin, first building up systems of control, and then watching as they collapse. Really though, I liked it because it was clearly written, short enough to get through in an evening, and will be good for answering essays on. What more could I possibly want?

For more writers of this period, there’s Hofmannsthal, Trakl, and Sandor Marai to consider.