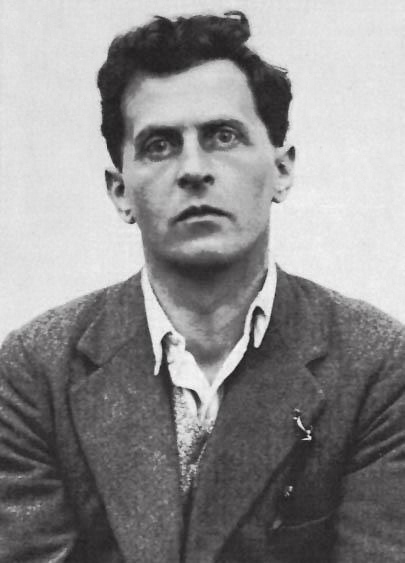

Ludwig Wittgenstein was an enigma: a radical philosopher with an overriding impulse to understand how the world worked, whether that be the mechanics of aeroplane engines or the logic of language itself. He had a mind of ice, pure and clean. In 1913 he went to Norway to be alone in the mountains and focus entirely on his philosophy. He gave away all his inheritance (billions in today’s money), wore the same clothes, and ate more or less the same food, whenever he could. It seems plausible that he had autism.

Yet for all his coolness, in 1914 he enlisted voluntarily in the Austro-Hungarian army and faced combat on the Eastern front against the Russian army, where he was awarded for bravery. This same steely logician also had the habit of coming to Bertrand Russell’s rooms in Cambridge and pacing for hours into the early morning, declaring he would end his life as soon as he left, and then thinking and thinking before the exhausted Russell until he found a solution or scrap of progress that meant he returned to his rooms only to sleep.

These two Wittgensteins seem in conflict with one another, and I previously wrote about them while reviewing the excellent Wittgenstein’s Vienna, which paints a far more hot and fiery cultural and intellectual milieu for Ludwig to grow up in than his philosophy reflects at first glance. Really, though, Wittgenstein seems to me a thinker who was utterly obsessed, tormented, and battered relentlessly, by questions of meaning and action. What must we do, and why. Suddenly, every word he wrote seems to reflect the attempt to build a logical scaffolding from which better to consider and resolve these problems of action and meaning.

A Man at War

It is the Wittgenstein at war who is the topic of the piece. What happened between 1914 and the completion of the Tractatus in a prisoner-of-war camp in Italy in 1918 is fascinating. For while much of the logic of the book had been written previously, in Norway, it is here, with death a regular companion, that the sixth section of the Tractatus took shape. The “mystical”, the “higher”, all those things that so alarmed Russell when the two met after the war was over, yet which seem to have been utterly vital in the most literal sense of that word, were added during this time.

In Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Meaning of Life, edited by Joaquin Jareno-Alarcon and published earlier this year (the piece was written in late 2023), we have an incredible treasure trove of material to work with. The book aims to gather together all of Wittgenstein’s comments on ethics and religion, whether in diaries or letters, notebooks or second-hand through the memoirs of others. It gives us an incredible insight into the man, the sort that would only be available otherwise to a specialist. I keep coming back to things in it, over and over. It is here, in Wittgenstein’s most private moments, that he seems willing to fill in the gaps of the Tractatus.

The Diary

There is a curious feature to Wittgenstein’s diary of this period. On the left-hand side, we have the mundane, and on the right, he wrote his philosophy. At first, there was no link. The extracts Jareno-Alarcon selects describe Wittgenstein’s army work and his feelings. To give an example: “In post from 1-3. Slept very little.” What merits their inclusion in the collection is Wittgenstein’s inevitable referral to God and the Devil, who emerge as very real forces within Wittgenstein’s life: “It is enormously difficult to resist the Devil all the time. It is difficult to serve the Spirit on an empty stomach and when suffering from lack of sleep!” The philosopher G.E.M. Anscombe said that Wittgenstein told her he lost his faith when still a child. So how then do we explain such utterances, which are extremely regular and indeed run right through to his death?

It seems a cop-out to say merely that God is the world, i.e. the totality of facts, as it is defined in the Tractatus. Certainly it is. But these extracts show a man who is having a very real, very challenging relationship with two forces – I won’t say beings. They seem constantly on his mind. Many readers would be bored to death by the strangeness of the text if that was all there was to it. On the other side of the page, from 1914 to 1916, logic plods along and the Tractatus takes further shape. The two halves of Wittgenstein’s life, the clean precision of logic and the messiness of human reality, are separated by an impermeable barrier.

And then, on the 11th of June 1916, as the Russians conduct a major offensive on the battlefield, they not only punch through Austrian defences – they also punch through this barrier in Wittgenstein’s own world. Here is the diary entry for that day, in the philosophy column:

What do I know about God and the purpose of life?

I know that this world exists.

That I am placed in it like my eye in its visual field.

That something about it is problematic, which we call its meaning.

That this meaning does not lie in it but outside it.

That life is the world.

That my will penetrates the world.

That my will is good or evil.

Therefore that good and evil are somehow connected with the meaning of the world.

The meaning of life, i.e. the meaning of the world, we can call God. And connect with this the comparison of God to a father.

To pray is to think about the meaning of life.

I cannot bend the happenings of the world to my will: I am completely powerless.

I can only make myself independent of the world – and so in a certain sense master it – by renouncing any influence on happenings.

This is, as far as I am concerned, real philosophy. This is a person with a phenomenal mind trying, very hard and for themselves, to think about big questions. When I read this for the first time I felt elated, giddy. This is the kind of thing that is exciting. It was like someone was for the first time pointing at a stain that only I seemed able to see and saying “there, there it is!” And he was standing beside me. In a way, it’s probably the most serious, most personal thing I have ever read.

Another entry soon after it runs:

To believe in a God means to understand the question about the meaning of life.

To believe in a God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter.

To believe in a God means to see that life has a meaning.

The world is given me, i.e. my will enters into the world completely from outside as into something that is already there.

(As for what my will is, I don’t know yet.)

That is why we have the feeling of being dependent on an alien will.

However this may be, at any rate we are in a certain sense dependent, and what we are dependent on we can call God.

In this sense God would simply be fate, or, what is the same thing: The world – which is independent of our will.

I can make myself independent of fate.

There are two godheads: the world and my independent I.

I am either happy or unhappy, that is all. It can be said: good or evil do not exist.

A man who is happy must have no fear. Not even in face of death.

Only a man who lives not in time but in the present is happy.

For life in the present there is no death.

Death is not an event in life. It is not a fact of the world.

If by eternity is understood not as infinite temporal duration but non-temporality, then it can be said that a man lives eternally if he lives in the present.

In order to live happily I must be in agreement with the world. And that is what “being happy” means.

I am then, so to speak, in agreement with that alien will on which I appear dependent. That is to say: “I am doing the will of God.”

Fear in face of death is the best sign of a false, i.e. a bad, life.

When my conscience upsets my equilibrium, then I am not in agreement with Something. But what is this? Is it the world?

Certainly it is correct to say: Conscience is the voice of God.

For example: it makes me unhappy to think that I have offended such and such a man. Is that my conscience?

Can one say: “Act according to your conscience whatever it may be”?

Live happy!

In the Tractatus, we have only a little to go on. Wittgenstein does not attempt to talk about that “about which we should be silent”, as he does here. But still, there are moments that are tantalising, which these two extracts and the others in the book explore in greater detail. Like the moment when he says, in 6.43, that “the world of the happy is a different one from that of the unhappy”, or, in 6.521, that “the solution to the problem of life is found in the vanishing of the problem.”

The ethics that we discover Wittgenstein as having during the First World War are actually not at all complex. They are, in fact, undoubtedly influenced by Tolstoy, whose Gospel in Brief Wittgenstein carried with him all through the war. Tolstoy, like Wittgenstein, came to value the conscience highly. Both men struggled, throughout their lives, with an overpowering sense of guilt, which partly explains it.

Thinking about life as a stage

Yet what does Wittgenstein actually say? What is his vision of the world here? With the help of an influential essay by Eddy Zemach on “Wittgenstein’s philosophy of the mystical” and an extended metaphor, we can perhaps summarise. The facts of the world are as they are. We arrive upon a stage which has been set out already, ready for us to play out our role. God is not a person – God is the stage, we can say. God is the world, is the arrangement of all things that we have to make use of while we perform – “we are dependent on what we can call God.” If there were no world, there would be nothing at all to stand on.

It is mysterious that there is a world at all. How things are, that’s not a problem. (6.52, “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions were answered, the problems of life would remain completely untouched”). Science can explain the world just fine – its composition, its creation even back at the Big Bang. The world, the entire universe and all the things in it, are again this stage, or perhaps an entire theatre. But we cannot see beyond the stage. No matter what discoveries we make, we are limited in this. Yet we may have a sense that there is something more, something that cannot be explained – why there is a stage at all. Indeed, on stages people perform. Yet what are we to perform and why?

“There are two godheads: the world and my independent I.” We come into the world and like it, or have a problem with it. If we have a problem, we are not happy. Our unhappiness can be reconsidered as a feeling that if we were to die, we would be upset as death approached. “Fear in face of death is the best sign of a false, i.e. a bad, life.” This fear is the result of a bad conscience, and bad conscience is finding that we are not living in a way that is harmonious with things. We go around the stage, frustrated at the chairs and tables placed on it. We constantly stub our toes on the world as it merely is.

The way to be happy is to accept the world. To use the chairs as chairs, to sit at the table, to play a role that the stage allows. Wittgenstein’s idea in this period is that we must follow our conscience, while also accepting the world as it comes to us. It is obvious that such a view comes easily from the experience of war, where we come face to face with evil and death and pointless suffering with a monotonous regularity. If we accept this state of things, then that’s part of the way to happiness cleared up – the world does not upset us.

The next stage is to follow our conscience. Once we accept things, we need to know how to act. Also, just as we can get the world to stop upsetting us by accepting it, we can get ourselves to stop upsetting us, by aligning ourselves with our conscience. Asking our conscience what to do will let us act in a way that is right to us, so that if we were to face death we could not say to ourselves that we had done something wrong. There can be no guilt to expiate if we were true to our own obligations, as we felt them.

In entries both before and after the war, Wittgenstein struggles with the voice of his own conscience, because it places great demands on him. For example, he feels he must write a confession of his sins and give it to all his friends. He does not do this, and so he makes himself miserable. But unlike with one’s attitude to the world, our conscience seems harder to change. And so, we are better off following it.

“I am conscious of the complete unclarity of all these sentences.” What we have here are just ideas that Wittgenstein toyed with as he faced the Russians’, and then the Italians’ bullets and bombs. We can see stoicism, but more than that we will recognise the influence of Schopenhauer, whose ethics consists simply of extinguishing one’s own desires while trying to reduce the suffering of others. Wittgenstein’s ethics shares the idea that one should not desire for things to be other than they are, while emphasising the importance of one’s conscience in inevitably leading us to help others, presuming our souls retain the ability to see and mourn their sufferings.

We can and should ask whether these ideas survive the battlefield. By the time the war ends, it seems that Wittgenstein has indeed stopped thinking philosophically about God and wills. “Let’s cut out the transcendental twaddle when the whole thing is as plain as a sock on the jaw”, he writes to a friend, Paul Engelmann, in 1918. And there must be a reason why the Tractatus itself is so quiet on these things. (Because we are not supposed to talk about them, perhaps). Yet as we read beyond the bounds of this post’s timeframe, we find that Wittgenstein the individual does not move on. He is still coming back to overwhelming feelings of guilt, to the falsity and baseness of his desires, and he is still talking about “God” and the “Devil” in ways that seem to go beyond just considering these two synonyms for words like “fate”.

Now, as a way of living, we might find plenty of problems with this worldview. It may not seem true to our experience. We may note that war, in fact, can easily warp and ruin the conscience, in a way that seems unacceptable to those who haven’t experienced it, but which does not matter to those who have. (Someone with a ruined conscience cannot really understand what they’ve lost). Yet enough of these ideas appeal to me that I keep coming back to them. Though he does seem to have had a life of torment and personal struggle, given his conscience and sense of guilt I doubt Wittgenstein could have survived existence any other way. Perhaps we should take him at his word when, dying, he said “tell my friends I’ve had a wonderful life.”

Conclusion

I spend a lot of time myself in conflict with my own conscience. Most of my wasted and hence ultimately saddest moments come from ineffectual attempts to avoid my conscience, numbing it in various ways. If I were to face death now, I am not sure I would manage it well. Not primarily because I would be upset for those I leave behind – for like Wittgenstein, your blogger is on a certain spectrum – but because I know that there are falsities in my life that require remedy. I would regret, and regret much.

A friend of the family is a doctor in Switzerland, the sort whose patients are extremely wealthy and mostly on their way out. According to them, most of their patients scream on their deathbed, a little like Ivan Ilyich. I tend to see this as an indication that the kind of life that leads to you dying wealthy in Switzerland is often incompatible with the Last Judgement (another phrase Wittgenstein used wholly seriously, funnily enough) you make of yourself and your life. It is certainly something to consider as we make decisions about careers, families, and related matters.

There are other explanations, of course. If we truly love life, we will be loathe to part with it. We may be upset for our loved ones, losing us. But in any case, considering whether we have a bad conscience, or whether we would scream and scream if death came suddenly to us in the near future, is probably a good rule-of-thumb when assessing our own lives. Given it’s almost the New Year as I finish this post, it’s the perfect time to audit ourselves.