Report to Greco was pretty much the last thing the great Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis wrote, and though it is complete in and of itself, it was only really a first draft. It is an autobiography, but not of the sort that most of us are used to. In spite of a fascinating life full of adventure and travels, in Report to Greco the focus is very much on the internal adventures of the mind. Kazantzakis explores the spiritual discoveries, challenges, and epiphanies that made him who he was as a person and, equally importantly, as a writer. It is a beautifully written book, challenging and rewarding in equal measure, and easy to recommend to one tormented by those accursed questions: what must we believe, and what must we do?

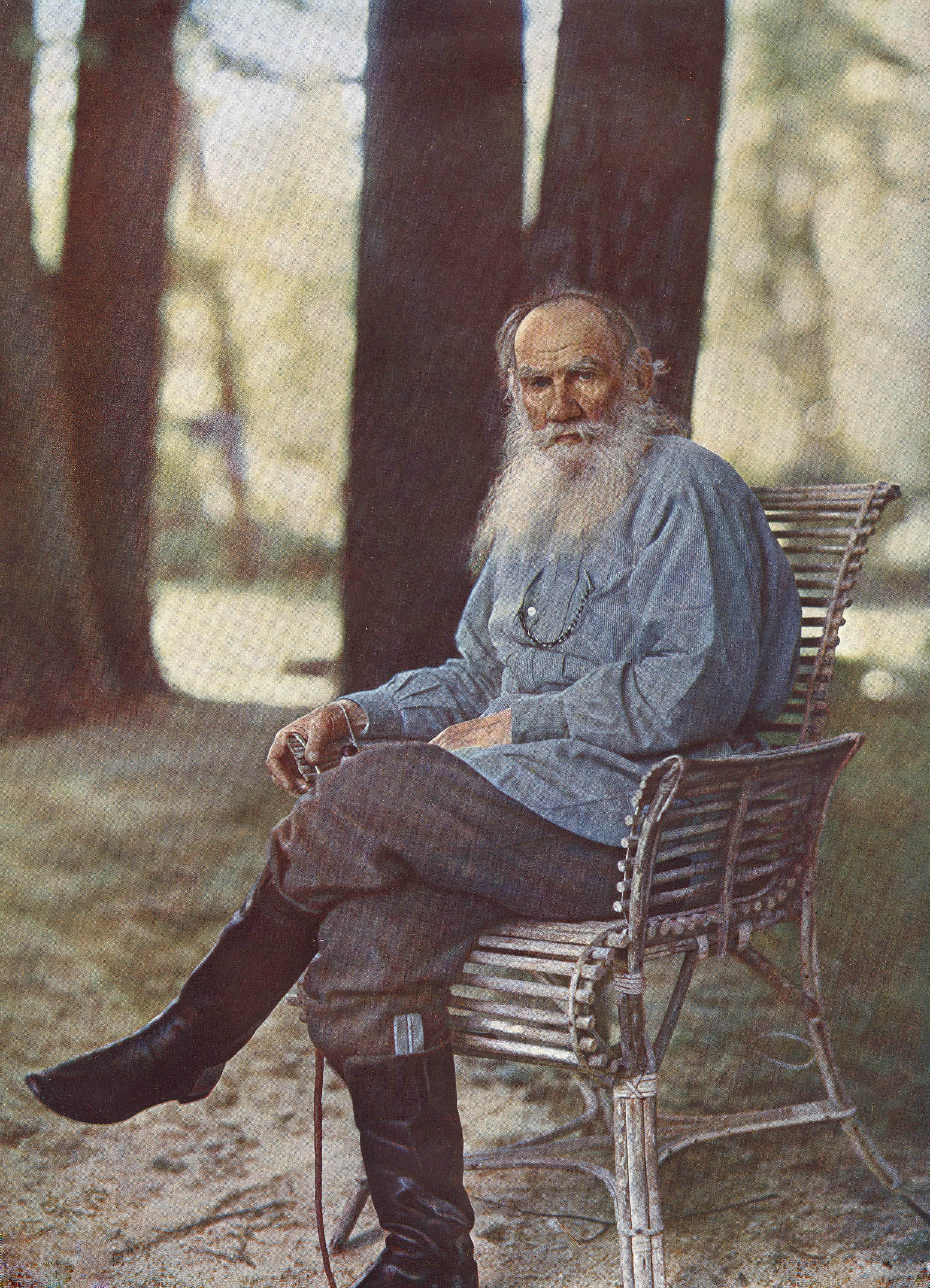

I loved it. For the truth is, except for the pressures of reading lists and friends’ recommendations, I read for the same reasons I live – to find a justification for my life, and a way of looking at the world that redeems it and all its suffering. In this journey many writers have helped me – Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Whitman, and Rilke come to mind – but no author of fiction, in a single book, has been so determined to find answers as Nikos Kazantzakis in Report to Greco.

“My life’s greatest benefactors have been journeys and dreams. Very few people, living or dead, have aided my struggle.”

At times the dominant force is Nietzsche, at times Homer or Bergson or Buddha or Lenin. To go through Report to Greco trying to plot the exact nature of Kazantzakis’ growth is a fool’s errand. He contradicts himself, forgets himself, and repeats himself. As we ourselves do, in our own development through life. To read this book is to be bourn along a river whose current and banks are ever-changing. The journey is more important than the specifics precisely because it is Kazantzakis’ attitude that is most memorable here. In Report to Greco he demonstrates how life can truly be lived according to the injunction memorably stated by the dying Tolstoy “Search, always keep on searching”.

It is not enough to know that Kazantzakis had engraved on his gravestone: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free”. It is not even enough to know his intellectual forebears. It is necessary to know the attitude that could guide a man’s life such that at the end of his days he truly could believe in those words and rest. That story of a life is Report to Greco’s gift to us.

The Structure and Messages

Report to Greco is not really an autobiography, and trying to read it as one is a little foolish. Comparing it even to Kazantzakis’s Wikipedia page is going to lead to a lot of confusion. In spite of the book’s length and variety, it seems that there remained a huge amount of Kazantzakis that he nonetheless conceals, or else thinks is not worth writing about – “rinds they were. You tossed them into the garbage of the abyss and I did the same”. The book’s introduction by Kazantzakis’s widow, Helen, explains that as Kazantzakis lay dying he was nonetheless remembering still more events, still more travels, which would have made it into a second draft. These passed away with him. But so much is here that we have little to complain about.

Report to Greco begins in Kazantzakis’ home in Crete. It talks of his quiet mother and warlike father, and of ancestors on both sides. The teachers who influenced him, the schoolfellows who first accompanied him, and later disappointed him, are all described lavishly. I have not been to Crete or even Greece, but after Report to Greco and Zorba the Greek I feel like I need to go soon. Still, Kazantzakis doesn’t stay long in his homeland. Soon he begins the travels that make up the majority of the book. To Italy, to France, to Germany, Austria, Russia, the Caucasus, Jerusalem… the list is almost endless. And certainly, if Kazantzakis had lived longer, no doubt it would have been. His companions are monks and priests and poets and thinkers. Their conversations range widely, but always reflect Kazantzakis’s occupation with the big questions. What must we do, and what must we believe?

From everyone he gets a different answer. From the monks on Mt Athos he gets one, from the monks on Mt Sinai another. The revolutionaries of Russia give him faith in humankind – at other moments it disappears. At times God exists, at times a void. And when we reach the end of the book I’m not sure we’re all the wiser as to what Kazantzakis actually believes, except for in those big ideas that would seem cheap without the whole of Report to Greco to serve as their explanation and justification.

Of freedom he writes:

“love of liberty, the refusal to accept your soul’s enslavement, not even in exchange for paradise; stalwart games over and above love and pain, over and above death; smashing even the most sacrosanct of the old moulds when they are unable to contain you any longer”

And then of his own life there is this cryptic message:

“I was becoming a sea, an endless voyage full of distant adventures, a proud despairing poem sailing with black and red sails over the abyss.”

God is not important, because “the very act of ascending, for us, was happiness, salvation, and paradise.” But God, perhaps, lurks at the end. The achievement of Report to Greco is to make God irrelevant by showing how much of His creation can be enjoyed and savoured by us while we are still among the living. Affirmation requires a creator, but it doesn’t require a Beyond at all.

Travel and the Language of Affirmation

Report to Greco is a journey of the body as well as of the spirit. In some way, the journey of the latter needs the journey of the former. Through different people, and through different books, Kazantzakis comes to flourish. But as I reader I loved the places too, and though this is not a travel book, Report to Greco still has a lot to say about the locations Kazantzakis passed through during his life. We get the sense that places were inhabited by their ideas and beliefs just as much as they were by people. As he heads towards Mt Sinai Kazantzakis writes of the place: “This arid, treeless, inhuman ravine we were traversing had been Jehovah’s fearsome sheath. Through here He had passed, bellowing.” I too have had the experience, in the Himalayas and the desolate Pamir mountains of Tajikistan, of feeling a spirit passing in the wind.

Kazantzakis’ language also contributes to the feeling in Report to Greco of being closer to these big questions. His prose is always straightforward, and his images are influenced by his upbringing on Crete and his love of the Classics. These images reflect the rawness of his passion in searching for answers, and drag us after him. Our own images are often cliched and soulless and keep listeners and readers from truly feeling the truth of our own feelings, our own spiritual upheavals.

Meanwhile, who can read something like this without feeling its power, even if you do not believe it? – “Away, away! To the wilderness! There God blows like a scorching wind; I shall undress and have Him burn me.” Or his words on a statue: “Just as a hawk when it hesitates at the zenith of its flight, its wings beat and yet to us it appears immobile, so in the same way the ancient statue moves imperceptibly and lives”. I myself can scarcely differentiate a hawk from any other such bird, or the trees in the forest. I lack that knowledge, that experience.

On his own style Kazantzakis writes “In vain I toiled to find a simple idiom without a patchwork of adornments, the idiom which would not overload my emotion with riches and deform it.” Kazantzakis’s regular use of such natural images is part, I think, of the whole thread of affirmation in Report to Greco. He lives in this world more closely than I do, and by using the world in his images he shows the value he finds in it. The riches are in the world, not in the virtuosity of the language he uses to describe it. As a result, the language is breath-taking because it’s the product both of love and of experience. Few modern writers have both, at least where nature is concerned.

A Few Complaints

There are problems here, and things that are out of date. The contradictions and repetitions in Kazantzakis’s spiritual development would probably be cut by a harsher editor, even though they likely reflect what he actually experienced. The fact is, a repeated epiphany loses much of its value to a reader. Still, I like the way that the current structure demonstrates just how we can reach the same conclusions from many different circumstances. In some way that reinforces what I feel to be one of the book’s underlying messages: it is the attitude we take to things rather than the specific experiences we have that count for becoming who we are.

Less easily looked past are the instances of old-school sexism, which is really just a little boring. (“Women are simply ornaments for men, and more often a sickness than a necessity”) This is a man’s spiritual journey, and it often feels like women are excluded from the peak Kazantzakis is climbing towards. All the same, the sexism here isn’t as bad as it is in Zorba. Much worse, however, is the tacit defence of Stalin. Report to Greco was written in the years immediately after Stalin’s death so there’s really no reason for Kazantzakis to be so silent on Stalin’s atrocities – in the Soviet Union Khrushchev hadn’t exactly kept quiet himself. I also cannot believe that Kazantzakis wasn’t aware of them either, since he travelled so widely in the Soviet Union. All he has to say, however, is these words, given to his female companion at the time.

“Lenin is the light, Trotsky the flame, but Stalin is the soil, the heavy Russian soil. He received the seed, a grain of wheat. Now, no matter what happens, no matter how much it rains or snows, no matter how much it fails to rain or snow, he will hold that seed, will not abandon it, until finally he turns it into an ear of wheat.”

Well, this, and a little story about Stalin’s bravery while he was a revolutionary in Tbilisi. Isn’t that great? The irony, probably not deliberate, is that Stalin might have had a much easier time growing his seed if he didn’t actively cause huge famines in modern-day Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Genocide doesn’t grow fruits, and I’m disappointed Kazantzakis leaves any dark from his portrayal of Stalin. It would be better not to mention him at all if this bad taste in the mouth is all we’re offered. Kazantzakis’ love of the Revolution’s ideals is perfectly understandable – the chapter taking place in Russia has a particularly memorable moment where Kazantzakis witnesses a large parade and feels a great unity with his fellows. But it’s a real shame he didn’t think Stalin could be separated from his revolutionary origins.

Conclusion

There are many reasons to read Report to Greco, but enjoying it demands an open mind. The book rewards those who are willing to let themselves be bourn across time and space through Kazantzakis’s life. If we ourselves are not searching for answers, Kazantzakis’s desire to find them will no doubt seem somewhat foolish. But if we are, then even if we don’t agree with his conclusions – and why should we? – we will appreciate the spirit that drove him to reach them. Kazantzakis’s attitude towards life is what inspires me most of all. The German-language poet Rilke wrote in his Letters to a Young Poet that we must “live the questions for now”; Kazantzakis shows what such a life can look like. This is the great gift of Report to Greco. The task now, for all of us searchers, is to go out filled with the same faith that animated him and find our own.

And then perhaps, we may come to have upon our headstones the same words that lie on his. “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free”.

Have you read Report for Greco? What did you think of it? Let me know in the comments below.

For more Kazantzakis, look at Zorba the Greek here. For more affirmation of human existence, look at Platonov, Shalamov, and Rasputin. If you want more old school beauty and simple living, look at Satta’s Day of Judgement.