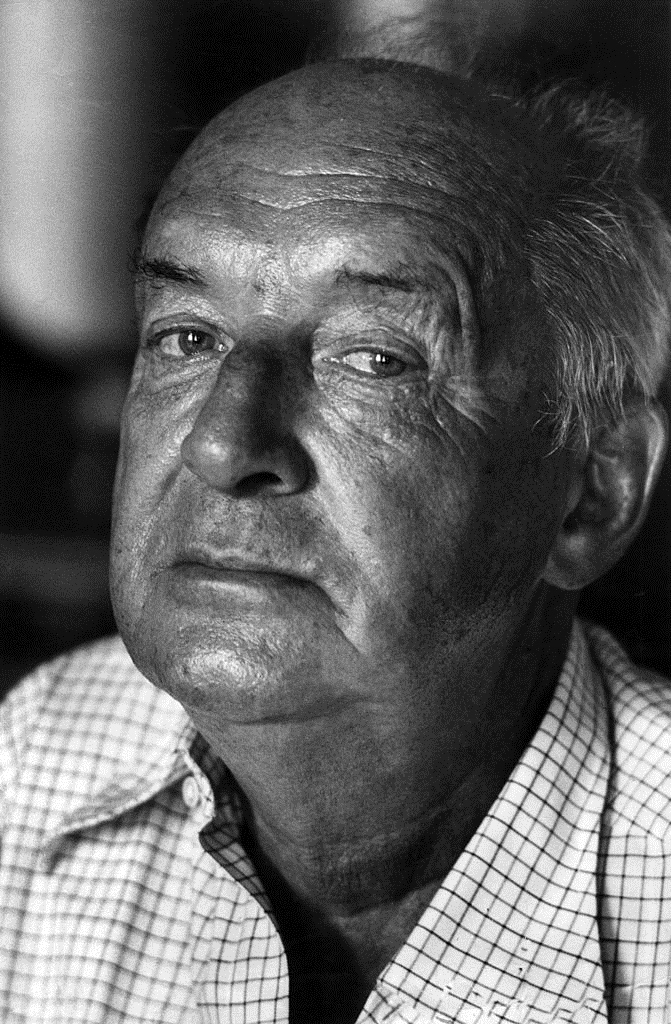

Introduction: Isaac Babel and his World

War is a time and space of rapid change, of unrivalled destruction but also of the creation and recreation that comes in its aftermath. In 1920 a young Russian Jew of Odessa accompanied the newly formed armies of the Soviet Union in their war against Poland. Isaac Babel, friend of Maxim Gorky, had been given the role of war correspondent through his connections to the other writer. Gorky saw Babel as needing first-hand experience to improve the quality of his writing. What came out of this time was a cycle of short stories, Red Army Cavalry (Konarmiia), a work of both beauty and brutality. Babel’s stories, published separately in the 1920s before being collected together, showed a new revolutionary world being born, and all the ambiguity it brought.

Babel’s work in these stories is of vital importance to understanding Soviet culture because it contains within itself the two trends that were later to become dominant in it. The first, in works lying outside of state approval and published only clandestinely if at all, criticised the state for claiming to have made a utopia reality when in practice they had made a lie leading only to suffering; the second view, however, which developed into Socialist Realism, was one that promoted the Russian Revolution as creating a new and better world, which saw bright hopes and the chances to put them into action, and a new type of heroism, accessible to all.

Babel expressed both views with equal care, and for this his collection is important in a world where views of the Soviet Union tend to be particularly black-or-white. But these stories are also intellectually challenging, extremely well-written, and even at times entertaining. And that doesn’t hurt them either.

War and its Representation: The Structure of Red Army Cavalry

The great Russian war novel is the aptly titled War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy. At well over a thousand pages it conveys the totality of war by describing everything Tolstoy can think of that is connected with it. Red Army Cavalry is, by contrast, tiny. The stories themselves are only ever a few pages long, and the whole book in my edition is just over 150 pages. But Babel was a huge admirer of Tolstoy’s, and his influence is felt here, albeit in a sublimated form. Whereas Tolstoy aimed to write about everything, Babel felt that such an option was no longer open to him.

Faced with the horrors of war, and aware of his own limits as a witness, he wrote what comes together to be a fragmented novel rather than a short story collection. Characters recur, and each story chronologically follows on from the previous one, as the cheerful optimism of the Soviets is replaced by concern as they begin to suffer losses, and then fear as they are routed. The narrator is a man called Liutov, which was Babel’s own name while he was working as the war correspondent, and the two men share other similarities that blur together fact and fiction. Babel made liberal use of his diary for creating these stories, so that it is hard to tell where Babel ends and Liutov begins.

By showing an individual’s challenges during war, Babel can focus on the reality of suffering rather than the abstractions that are inevitable when trying to paint a bigger picture. Liutov encounters many of those affected by the warring armies, from Catholic priests in Poland to smaller Jewish communities in modern-day Belarus, to simple peasant men and women. Even as an individual there is enough material to bear witness to. And whenever Babel wants to expand beyond this, he uses the Russian technique known as skaz, similar to free indirect speech it is where characters speak in language and styles clearly distinct from those of the author. For example, in the story “The Letter”, a young boy, Kurdyukov, dictates a letter for his mother to Liutov. In this letter he reveals the extent of his own, personal suffering in the war in a way that Liutov himself cannot express on his own, except by recording it.

The Prose of Sympathy and Absent Judgements

What Babel takes from Tolstoy is not a grandiose scale so much as a sense of sympathy towards the world and its inhabitants, and a lack of direct judgement on them. He takes time to focus on the specific and concrete casualties of the fighting in ways that challenge the simplistic metanarratives of war being merely a tug-of-war between opponents.

The first story, “Crossing the River Zbruch”, is representative of this. It begins “The leader of the Sixth Division reported that Novograd-Volynsk was taken today at dawn” (translations mine unless otherwise noted) – the tone here is formal and military. But by the second paragraph there is a shift from the objective towards a more subjective and poetic appraisal of the landscape: “Fields of purple poppies are blossoming around us, the midday wind plays in the yellowy rye, and on the horizon the buckwheat rises like the wall of a far-off monastery”. Death, hidden in official reports under mere statistics, breaks through in images like that of the orange sun that “rides across the sky like a decapitated head”.

After these lyrical moments the bulk of the narrative takes place. Liutov enters Novograd and is billeted in a flat with a pregnant woman and three Jewish men, one of whom lies on the floor and sleeps. The descriptions of the poverty within the flat indicate more than the narrator’s frustration ever could what suffering the war has caused. The floors are covered with human faeces, while the pregnant woman’s very existence demands the question – by whom is she pregnant? The lack of judgement by Liutov encourages the reader to search the text carefully to determine for themselves what it might indicate.

This lack of narratorial judgement, analogous to the conclusions of Chekhov’s stories, is made even more glaring by the often horrific contents of the stories. At the end of “Crossing the River Zbruch” Liutov discovers that the pregnant woman’s father, who he’d thought was sleeping, is actually dead. “His throat was torn, his face was chopped in half, and dark blue blood lay in his beard, like a piece of lead.” This description of death is so different to numb cliché that we are forced to pay attention to it, to face the terrifying reality of war. Its presence invites judgement but does not make it. The pregnant woman has the final words of the story, explaining how the Poles killed him because it was “necessary”. Through his sacrifice she finds “a terrible strength” and pride in spite of her surroundings. Only in “terrible” is there hinted Liutov’s own reaction.

Culture Wars: Introduction

The world after the Russian Revolution was changing culturally just as much as it was technologically and politically. In some sense the change was a positive one, bringing art and artistic production down to the masses from being almost exclusively the domain of Russian elites in the capitals. Religion was dismissed as mere delusion, “the opium of the people” in Marx’s eyes, and science and rational thought were promoted as the alternative. Social progress on a grand scale, by the most forward thinking (in its own eyes) states ever to have existed, was the order of the day. A new type of hope was born, one that saw agency transferred from a mysterious God above into the hands of individual men and women.

But with all that there comes a question – what have we lost? Red Army Cavalry presents the two sides of progress’s coin through the times of the day, contrasting in daytime stories those who represent the new world with the characters of stories set at night, who represent an old world that, however irrevocably tainted it is, still retains something intangible and important for human life.

Culture Wars: Night and the Old Culture

Who are the people who lose out in the face of the Revolution and its consequences? Primarily it is the Jewish characters and the Catholics. Liutov himself is like Babel, Jewish, and thus as vulnerable as these others to the cataclysmic changes taking place. Within the stories the great representative of the old culture is the Jew, Gedali, from the story of the same name. In his story Liutov, late on the evening of the Sabbath goes out among the Jews of his current village, looking at the little stalls where they sell items like chalk to survive. The destitution makes him think of Dickens, and it is such appeals to an established literary tradition that reveal how culturally bound up in it he is.

Eventually he comes across the bench of an old man, Gedali, and sits down for a chat. At Gedali’s bench there are dead butterflies and other objects of fragile beauty. Yet with these symbols of culture there is a sense of its own negation, when Liutov smells “decay” underneath it all. Gedali is an educated man, and the two discuss the Revolution together. Gedali says he loves music and the Sabbath, but the Revolution tells him he doesn’t know what he loves. He talks of the violence the Revolution has led to and comments “The Revolution is the good act of good people. But good people don’t kill. That means that the Revolution makes people bad”. For all the idealism motivating the Soviets in this period, Gedali is concerned with its failed reality of it. In pain he famously asks Liutov “Which is the revolution and which the counterrevolution?”

Liutov has no real answers. His responses are pithy, thoughtless, as though plucked from a handbook on propaganda. “The Revolution has to shoot, Gedali… for it is the Revolution”, he says, obviously playing a different role to the one he plays in other stories. Soon enough he gets tired of his self-deception and asks where he can get some Jewish food and tea. Then he sets off to take part in the culture he was born into and cannot, though he tries to pretend otherwise with Gedali, escape. Meanwhile, Gedali goes to pray.

Closed indoor spaces, filled with decay and dust – these are the domains of the old culture. It is dying, certainly. There is a distinct sense of infertility in them, an absence of women and children. But for Liutov, and for other intellectual characters, it is absolutely necessary. It is a part of themselves that they cannot afford to lose.

Culture Wars: Sunshine and Cossacks in Red Army Cavalry

Loud and proud and colourful, the Cossacks stand out among the characters encountered during the day. They do not think beyond the present – neither past regrets nor the future hopes hold sway with them. They embody upheaval and joyous chaos. One of them is Dyakov, who was formerly a circus manager, and now is a soldier. He is described as “red-faced, silver-whiskered, in a black cloak”, as though he had never abandoned his roots as a performer. Colour is one way that the day-people stand out compared to the dull souls of the night. In their huge, larger-than-life poses and actions they are more than a little reminiscent of epic heroes.

They have no culture of the sort comprehensible to Liutov. Instead, they sing and one of them, Afonka Bida, at one point tries drunkenly playing a church organ in an act clearly symbolic of the usurpation of old culture’s place by the new. Their vitality is overpowering, and is usually marked by connecting them to their horses. They are often shown having sex or seducing women, demonstrating the sheer magnetic attractiveness of their love of life. They do not care whether they live or die, so long as in every moment they are living to the full. In this sense, it is hard not to wish to be like them and similarly free from restraint and concern.

But their freedom and joy is only one side of them. They come at a cost – their violence and unpredictability sets them outside of society and civilization, and for all their heroism, such as squadron commander Trunov valiantly facing down a biplane on his own like a modern day Don Quixote, under its surface Red Army Cavalry questions what good these people will be able to do once the war has ended and it is time to settle down. These are people who, thinking back to Gedali’s words, have made the Revolution and made it in their own image. The violence with which they carry out the Revolution also shapes it, and hardly in a good way.

Liutov’s Among his Comrades

Liutov, of course, fits in uneasily among his comrades. Two stories illustrate this. “My First Goose” is one of Babel’s most famous ones. In it Liutov is first mocked by the Cossacks for his appearance – like Babel he wears glasses – and for his education. Savitskii, one of them, suggests he defile a woman in order to be respected by the rest of them. Instead, he goes and kills a chicken with a sword in a mockery of his own hopes of being heroic before giving it to its owner, an old woman, to cook. The woman repeatedly says that she wants to kill herself, but Liutov ignores her, returning to his comrades. Now that he has killed he is accepted by them and addressed as “mate”. But the act leaves him feeling guilty, and during the night he dreams of the blood he has spilled.

The second story, “The Death of Dolgushov”, further demonstrates his failure to fit in. Dolgushov, a Cossack, is injured and dying from his wounds, which are described just as horribly as they are in “Crossing the River Zburch”. He asks Liutov to kill him, so that the Poles don’t find him alive to torture him further. But Liutov, filled with compassion and the humanist values common among the night characters, is unable to do it – his care paralyses him. Instead Afonka Bida has to finish the other Cossack’s life. As he does so, he says to Liutov: “Get away or I’ll kill you! You, four eyes, pity our brother like a cat does a mouse”. Values that seem so effective in books fail Liutov the moment he has to put them into practice. By the end of the story he has lost the little all the respect he had gained.

Pan Apolek and the New Culture

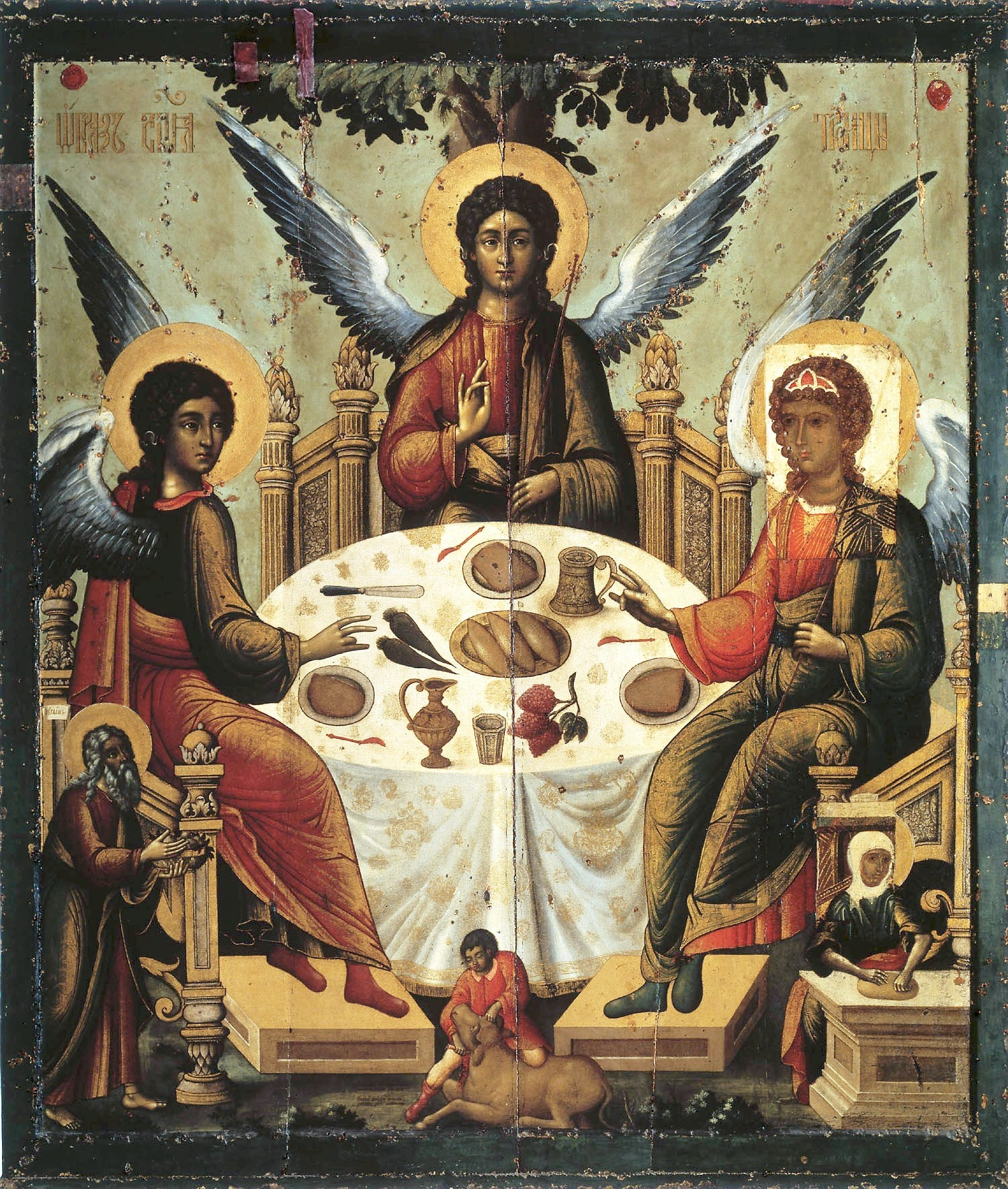

Pan Apolek is not a Cossack, but rather a Polish Catholic. Yet where the Cossacks fail to create a new culture out of the ruins of the old, Pan Apolek in his own story shows one way in which a potential synthesis of the old culture and the new is possible. Liutov first meets him at night, while he is having tea with his hostess, and then learns about his work. Apolek is a church painter, but with a difference. Traditionally such a person would go around trying to paint according to the strict rules of icon paintings, deviating as little as possible from an original image. Yet though Apolek paints Mary Magdalene, Jesus, and other Biblical figures, they are not modelled on originals but rather on local people. In this way he mixes high, religious culture with the low culture of normal people.

Though he is branded a heretic, he continues painting. His subjects include such blasphemous pairings as having Mary Magdalene be Yelka, a local woman who has given birth to many illegitimate children. What Apolek does is bring the high culture of religion down into the world, and in doing so make it more accessible. More than the revolutionaries themselves, he brings their ideals into practice.

Conclusion: Writing and Synthesis

Liutov is not the only writer here. In the story “Evening” several other war correspondents are depicted, each of them marked by illnesses, with Liutov’s being his poor sight. In vain one of them tries to convince a girl in the camp to sleep with him, but she instead joins one of the Cossack soldiers, unattracted by statistics and historical figures. But the very existence of Red Army Cavalry is itself an argument about writing and its use. As much as the Cossacks see little need for fancy metaphors and complex structures, Babel still gives them to us. He gives us stories of night and day, evening and the dawn. By writing about so many people, those who suffer from the Revolution and those who are made great by it, he encourages us to consider it not as good or evil, but as a mixture of the two.

A great deal of culture was lost, a strain of humanism of value seemingly disappeared, but in its place was a new world, filled with hopes and vitality. Liutov may be scrawny and bespectacled, but in writing this book Babel has made him, too, a kind of hero, because through these stories their emerges an attempt to shape the direction of cultural production within the Soviet Union, and with it an entire society, for the better. Like Pan Apolek, in the stories of Red Army Cavalry Babel syntheses two worlds, instead of letting one or the other get the better of him. If only his work had found more success instead of repression, perhaps the Soviet Union could have been a different place.

For more early Soviet literature filled with ambiguity, have a look at my piece on Andrei Platonov’s Soul and Other Stories. Alternatively, if you’d rather look at the dark side of the Soviet system directly, Varlam Shalamov writes wonderfully and grimly about the Gulag here.

picture of Babel, picture of Kalinin and Trotsky surveying the Red Army, picture of Chekhov, picture of a Cossack, and picture of an icon are all in the public domain