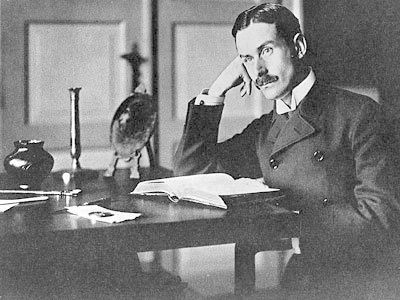

I confess I’ve never really gotten the hype with Thomas Mann. Or rather, the moment I start reading him I’m usually left either disappointed or confused. I blame his reputation. German students like me flock to read him but soon find they spend more time in the dictionary than the stories themselves. Death in Venice is a particular pain to understand the language of, and that’s not even half the battle of making sense of that tale. Nonetheless, once I read it in English (the poor Cambridge academics who supervise me are doubtless shaking their heads in disappointment) I found it rather enjoyable, and intellectually challenging too. Nevertheless, due to the arcane rules of Cambridge examinations I can’t talk about Death in Venice next year, though Mann himself remains on the syllabus. Looking for alternatives, I turned to “Gladius Dei”, hoping it would have something interesting to say.

“Gladius Dei” – I was attracted by the title, meaning “the sword of God” – is not nearly as action-packed as its title suggests. And nor is it as focused on the past as the Latin hints at either. Instead, it shows the clash between modern art and the sensibility that drove it with the older ideas that once justified artistic creation but which, in 1902 (the time of the novella’s composition), had very much fallen out of fashion. It is the tale of one man, Hieronymus, and his struggle against modernism as a whole.

Translations are from David Luke’s Death in Venice and Other Stories.

Introduction: Munich, the Fallen City

“Munich was resplendent.” “Gladius Dei” begins with a description of Munich, and Munich in some way is the main character of the novella. The German Jugendstil, their Art Nouveau, was at the height of its popularity in the city at the time the novella was written. From the very first paragraph, listing “festive squares” and “colonnades” and “fountains” we are immersed into this world of art. We meet the people, particularly women, who live in the city – as types, rather than as people. They are all relaxed and indolent. There is no rush about them.

Then we are taken into “the elaborate beauty-emporium of Herr M. Blüthenzweig”, where artistic reproductions and books are all on display, ranging in topic from the very modern to the classical. And here there is the first sense that art and its creation are not done in isolation, but influenced by consumers and their tastes – “among all this the portraits of artists, musicians, philosophers, actors and writers are displayed to gratify the inquisitive public’s taste for personal details.”

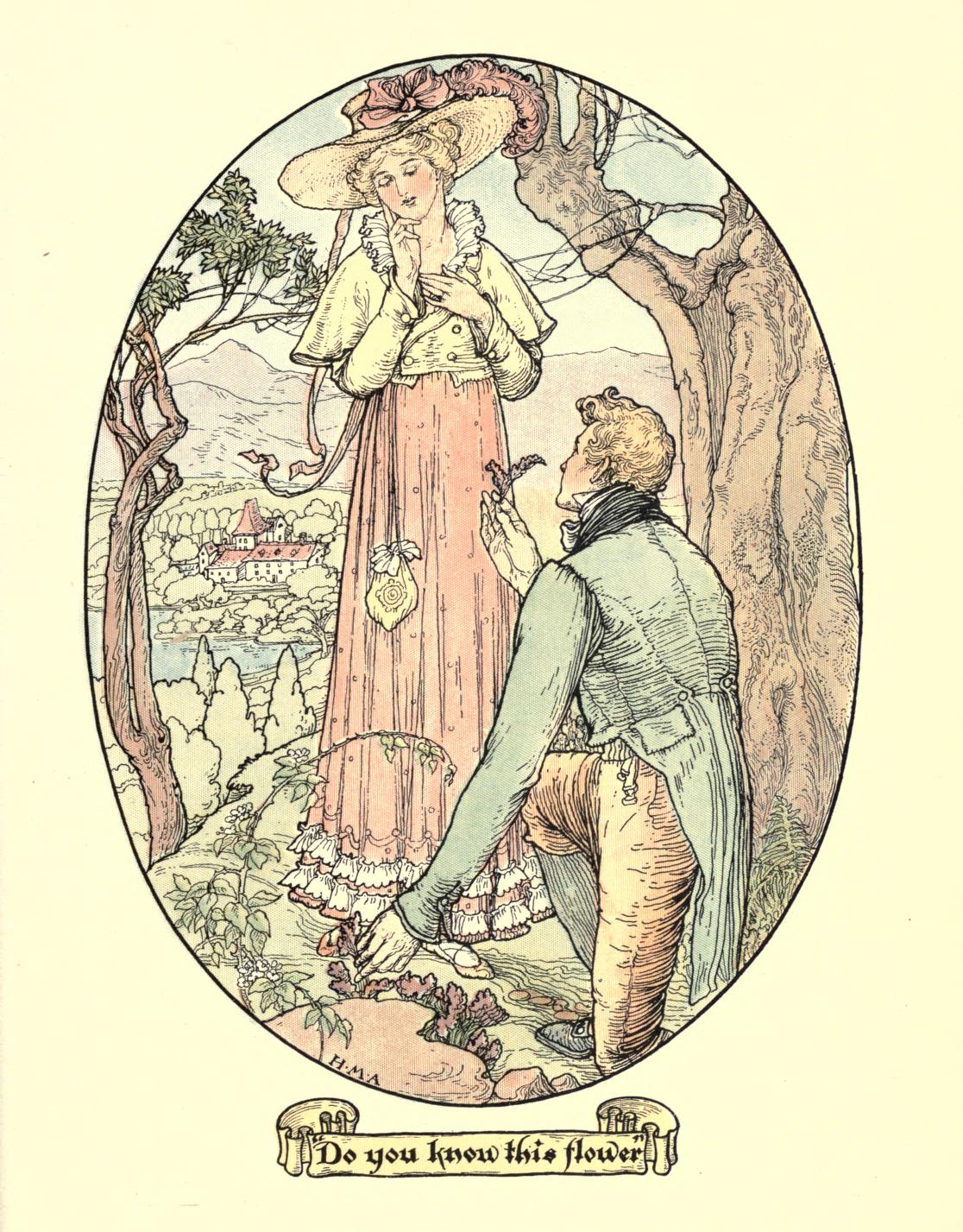

Next, we meet the key reproduction, which forms the focal point of the novella – but we don’t learn what it is in the novella’s first part. Instead, we are introduced to it through (literal) framing – “there is a large picture which particularly attracts the crowd: an excellent sepia photograph in a massive old-gold frame”. The frame is significant – its age contrasts with the contents, which are “sensational” and highly modern, promoted by “quaintly printed placards” and “this year’s great international exhibition”. Ironically, like the citizens of the novella, we are shown modern art by means of its popular reputation rather than its particular contents.

The narrative then moves back onto the street from its focus, completing the framing of the central picture. The final paragraph discusses the popularity of the art while returning to the novella’s opening words. “That it should continue so to thrive is a matter of general and reverent concern; on all sides diligent work and propaganda are devoted to its service; everywhere there is a pious cult of line, of ornament, of form, of the sense, of beauty… Munich is resplendent.” Though “Gladius Dei” ends its first part with the same words that begun it, here the tone is changed. From the purely celebratory beginning, now there is something seedy about the art – hinted at by words like “propaganda” and “cult”. It is this tension and seediness that the centre of Mann’s tale hinges upon.

Hieronymus and the Madonna

With the second section of “Gladius Dei” we are introduced to Hieronymus, whose name, reminding me of the artist Bosch, immediately conjures up images of the past. Against the brightness of resplendent Munich we are told that “when one looked at him, a shadow seemed to pass across the sun or a memory of dark hours across the soul”. He is inscrutable, but we are told he resembles a portrait in Florence of a monk who also raged against the world. In this way, Mann connects the present anger of Hieronymus with a historical precedent, that of the priest, Girolamo Savonarola. The two of them also share the same name.

Hieronymus first goes to a church on the Ludwigstrasse to pray, and then he comes across the art house of Blüthenzweig. Going inside, he sees the reproduction first mentioned in part 1 of “Gladius Dei”:

“It was a Madonna, painted in a wholly modern and entirely unconventional manner. The sacred figure was ravishingly feminine, naked and beautiful. Her great sultry eyes were rimmed with shadow, and her lips were half parted in a strange and delicate smile. Her slender figures were grouped rather nervously and convulsively round the waist of the Child, a nude boy of aristocratic, almost archaic slimness, who was playing with her breast and simultaneously casting a knowing sidelong glance at the spectator.”

This is sacrilege. A holy image turned lustful – “ravishing”, “sultry”, and the “knowing sidelong glance” all suggest that the glorification inherent in such a choice of subject has taken a back seat. Hieronymus overhears two young men discussing the painting, neither of whom respects its religious subject matter. “She does make one a bit doubtful about the dogma of the Immaculate Conception” one says. But they inform the reader that the painting has been bought by the Pinakothek Gallery and that its artist is being feted around the city. Their language is almost comically cultural, as if – to use the modern phrase – they are a bunch of posers. I would be surprised if this was not exactly what Mann has in mind. Hieronymus, meanwhile, finishes looking at the painting, and leaves, ending part 2.

Part 3 is only a page long, but it describes Hieronymus’ struggles to rid himself of the image of the sexualised Madonna. At last, however, “on the third night” he receives what he perceives to be a command from God, and decides that he must go and protest the display of such a work of art. And now the story approaches its climax.

Action and Inaction – the Bloodless Climax of Gladius Dei

Part 4 begins as Hieronymus heads onto the street, filled with righteous rage. “It is God’s will”, he thinks to himself, echoing the cries of “Deus Vult” that launched the first crusades. Outside the weather has begun to worsen, and a storm appears to be approaching. He reaches Blüthenzweig’s shop and goes inside, seeing evidence all around him for the spiritual decay of humankind. For example, there is a “gentleman in a yellow suit with a black goatee” who has a “bleating laugh” – both the laugh and the goatee suggest something animalistic about him. Coming across Blüthenzweig as he’s finalizing a transaction Hieronymus hears him call it “most attractive and seductive”.

Blüthenzweig is a capitalist, an art dealer with little appreciation for art itself. That is Hieronymus’ interpretation anyway, as he claims the dealer despises him “because I am not able to buy anything from you.” Meanwhile, Hieronymus is entirely concerned with the non-monetary value that art has. Is it good for the spirit, or not? In the case of the Madonna, he sees it as actively pernicious – “vice itself.” Blüthenzweig rejects this immediately – “The picture is a work of art… and as such it must be judged by the appropriate standards”. The painting has been bought by the gallery and is universally acclaimed. Both Blüthenzweig and Hieronymus have their own idea of what the “appropriate standards” are, but Blüthenzweig’s idea is marked by a focus on the external – acclaim – while Hieronymus’ is internal – “the spiritual enrichment of mankind”.

Hieronymus does not let Blüthenzweig convince him. He cries of hell, of the torments of purgatory. Beauty is a lie used by the representatives of Jugendstil to avoid considering the health of the soul. Instead, art ought to be “the sacred torch that must shed its merciful light into all life’s terrible depths, into every shameful and sorrowful abyss”. It must be about compassion, not beauty. Hieronymus demands that Blüthenzweig burns the reproduction, which naturally he does not have any interest in doing. He calls in Krauthuber, one of his workers, to throw Hieronymus out of the shop. Krauthuber is “a son of the people, malt-nourished, herculean and awe-inspiring” and with “heroic arms.” He represents, it seems to me, a sidestepping of the Christian view of art that Hieronymus represents towards the Classical, where art, especially if one takes Nietzsche’s view, was all about advancing the spirit and glorifying it.

Just not in the Christian sense of the spirit or glorification. Alone on the street, Hieronymus falls into madness, surrounded by the markers of a depraved age – “carnival costumes”, “naked statues”, and “the busts of women”. He sees them all piled into a pyramid and set to flames. It is here, as the novella ends, that he quotes Savonarola, who had had a similar vision of God’s vengeance, “Gladius Dei super terram… Cito et velociter” – “behold there is the sword of God above the Earth, fast and swift”. He has achieved nothing for his madness, but perhaps Hieronymus succeeded in saving his soul. Who can say?

Theories of Art and the Modernism of “Gladius Dei”

By the time that Mann is writing “Gladius Dei” Hieronymus’ view of art was well out of date. Even in the 19th century, art had already become popular, its form and content determined by market forces – think of Dickens in England during that time, or Dumas in France. That’s not to say that lofty goals had departed from artistic endeavours, but rather that they were often secondary to the need to feed oneself and one’s family, especially as artistic production became democratised and a new generation of writers and artists who were not aristocratic in background came to prominence.

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to see where Mann sits in all this. Though in “Gladius Dei” he shows the vapid banality of Blüthenzweig and his customers, Hieronymus is a ridiculous figure too. The contrast between the violence of the novella’s title and the ultimate lack of action and change seems to mock Hieronymus’ hopes to change society’s relation to art for the better. Likely, Mann sits somewhere in the middle – he respects Hieronymus’ love for the spiritual mission for art, while acknowledging the historical forces that make this view secondary, and indeed challenging to hold. The old values, in a world where “God is dead”, simply aren’t reliable anymore.

It’s also worth considering how the form of “Gladius Dei” reflects modernism in its composition. For one, there’s Mann’s ambivalence towards all of his characters, so that it’s not clear who is worth supporting, if anybody. Then there is also the satirical use of religion (just like the Madonna itself) and its language when Hieronymus thinks God is commanding him to defeat Blüthenzweig and the reproduction. It’s clear that Mann doesn’t think Hieronymus is really hearing God or want the reader to think so either. The inconclusiveness of the novella’s conclusion is also, in its own way, modernistic. We are given no guidance – it’s not even clear if we should pity Hieronymus. All, I think, that is clear is that the Jugendstil movement and the Christian artistic sensibility of Hieronymus are both inadequate in Mann’s view. But what is good art – Mann’s ideas on that are impossible to work out.

Conclusion

Personally, I’m closer to Hieronymus than Mann is. Not in the sense that I think literature and art should be about fulfilling a Christian message, but rather that I do think there should be a strong message in them about the value of humanity. A literature must be affirmative, glorifying our lives and life itself in all their complexity, whether good or bad. This is the secret to Tolstoy’s greatness. Mann doesn’t care enough about people for that. In this, he reminds me a little bit of Isaac Babel, another writer who is much more intellectual than emotional. It can make stories that are thought provoking, but terribly cold…

I thought “Gladius Dei” was ok. I mean, it’ll be easy to write about it next year once I’m back at Cambridge. But the measure of a book’s value isn’t how easily I’ll be able to ram it into an essay. I’ll keep reading Mann, but I hope one day I’ll understand where he keeps his heart locked away. Irony just doesn’t cut it for me – our own world is too ironic, too dispassionate, already. The solution to an ironic and dead world isn’t acceptance, but a conscious search for meaning and value, like Kazantzakis managed in Report to Greco. But perhaps I’m asking too much.

If you’ve read “Gladius Dei” and have an opinion on it, why not drop by the comments and let me know what you thought?