Joseph Roth’s novel The Radetzky March is a story of decline. On one level, it describes the rotting of an Empire, Austria-Hungary; on another, it is a much more personal story, telling the tale of three generations of the Trotta family, a family whose own rise and decline are both the result of their country’s decay, and in a way partly responsible for it. In dealing with the fortunes of a family, it is in some way comparable to Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, but The Radetzky March is a much tighter book, thanks to its focus on only three characters – grandfather Joseph Trotta, father Franz Trotta, and son Carl Joseph Trotta. As men, they are the administrators and soldiers of the great empire. As a result, their fates are inevitably bound with its own.

There is a lot to like about the novel. For me, above and beyond Roth’s talent for description and portraiture, what I loved most about The Radetzky March was its description of family and the shifting of the generations. My great grandfather became the world leader in his field and a household name; my grandfather became a famous and influential politician. But my father and his brother, the heirs, both found it difficult to live up to the expectations of the past and in some sense their lives can be read as an attempt to cope. It is now my turn, like Carl Joseph under the gaze of his grandfather’s painted eyes, to face the pressure to be someone I may not be.

The Radetzky March is not a source of guidance on this topic, but it is a picture of a world that is now lost, and we would do well to sift through the ashes in search of what might be worth holding on to.

The Birth of a Dynasty – The Opening of The Radetzky March

The first chapter of The Radetzky March is enough to decide whether the novel is for you. Detailing the life of grandfather Trotta, it works perfectly as a short story. We meet him in the army at the Battle of Solferino of 1859, where he saves the life of the young Austrian Kaiser, Franz Joseph. Joseph Trotta, who is the son of simple Slovene peasants, is ennobled for his deed. No longer is he a Slovene, now he is an Austrian – “a new dynasty began with him”. He receives a promotion, becoming a captain, and now is not merely Trotta, but “Trotta von Sipolje”. We might expect him to be happy, but instead the honour is more of a curse than a blessing. We feel his pain as his identity becomes uncertain, fragmented. “He felt he had been sentenced to wear another man’s boots for life”.

But he cannot return to the past either. When he meets his father again the conversation is stilted, awkward. The only thing for him is to try to become the aristocrat he supposedly is. Grandfather Trotta marries “his colonel’s not-quite-young well-off niece” – a lovely description conveying all the delicacy of aristocratic reasoning – and raises his only son with military constriction. “Never was the son given a toy, never an allowance, never a book, aside from the required schoolbooks. He did not seem deprived. His mind was neat, sober, and honest.” The son is not damaged by the life of discipline. These were different times, when individuality was less important than service. But things will change.

In the end, the father dies soon after the son comes of age. “Now little was left of the dead man but this stone, a faded glory, and the portrait. That is how a farmer walks across the soil in spring – and later, in summer, the traces of his steps are obscured by the billowing richness of the wheat he once sowed.” The rest of The Radetzky March concerns the wheat – his son and grandson, and their fates.

Fathers and Sons

Time changes. The father Franz Trotta grows up and now raises his own only son, Carl Joseph. He raises him in just the same way as his own father did. In these early chapters the only thing Carl Joseph seems to say to Franz (who is almost always referred to by his role, district captain) is “Yessir, Papa”, which indicates the degree of independence of thought the young lad has. There is no intimacy between them. They write each other letters, just as the grandfather wrote his own father letters, out of a kind of obligation and without any heart in them. When, later in the book, there are moments that put father and son together, they are unable to speak to each other.

Always he wanted to say, Don’t cause me any grief, I love you, my son! All he said was, “Stay well!”

Honour, of a sort

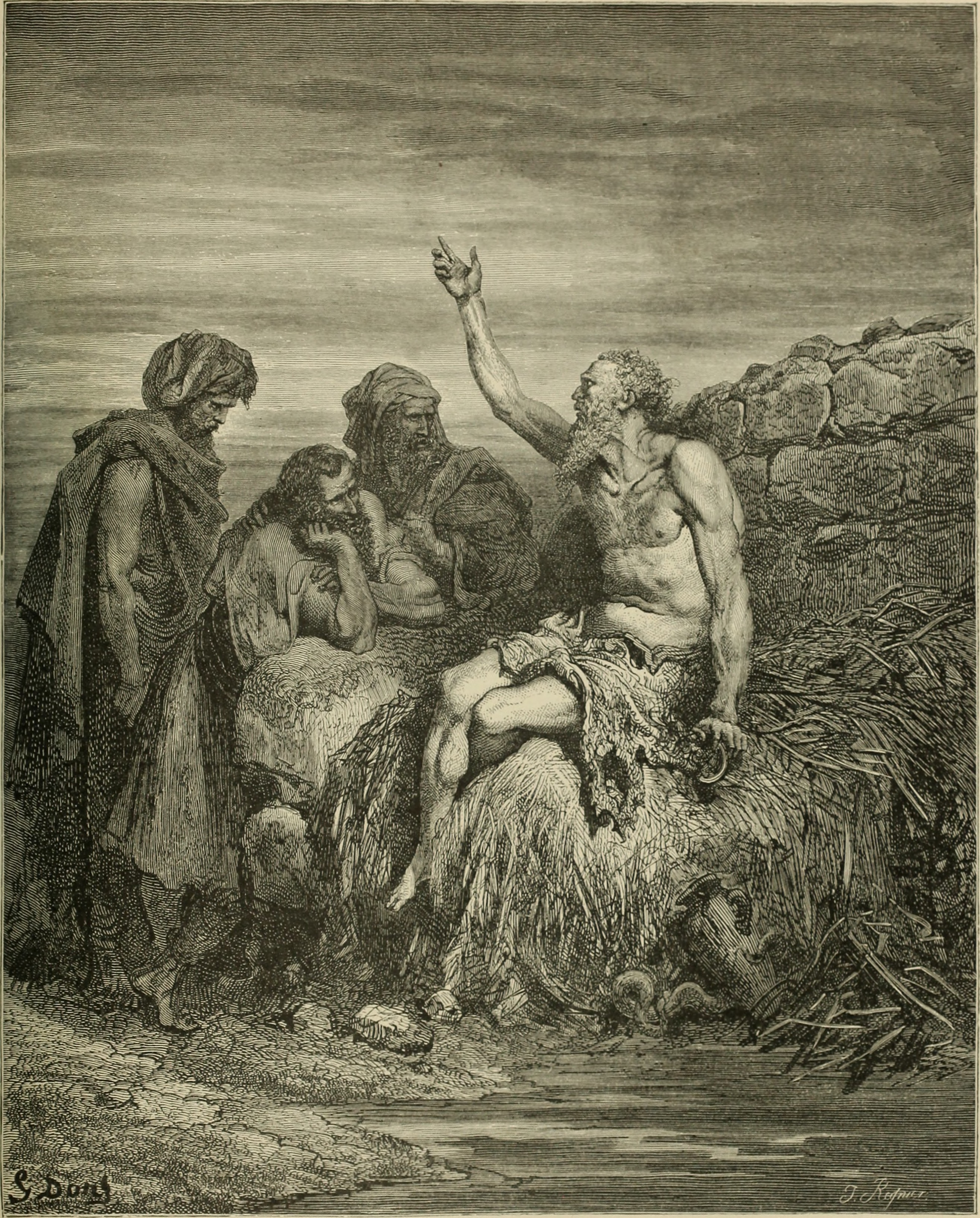

It is honour, that mysterious network of social rules and regulations, that binds both mouths shut. Honour is not all bad – it was, after all, a great source of dignity, and it bound together members of the upper classes with its common behavioural language. Nevertheless, honour places all of the characters of The Radetzky March in chains, whether they notice them or not. We see this most tragically with a young man, Max Demant, who Carl Joseph befriends early in his military career. He is in many ways a double of Carl Joseph – he, too, finds himself in a social position unthinkable to his ancestors. Demant is a Jew – his grandfather was a tavern keeper, his father a postal official. He is no soldier, no cavalryman, and his wife doesn’t love him. As he puts it, his is “a life with snags”.

One evening Demant departs a theatre performance early, leaving his wife alone. Trotta offers to escort her back, but they are seen by the other officers. The next time they are all together, the other officers drink heavily, leading one of them ultimately to start yelling “Yid, Yid, Yid!” Demant has no choice but to challenge the speaker to a duel. No choice? Demant knows that he has a choice – he knows there are ways to disappear, for example to flee to America. But he is unable to make that decision. “A contemptible, shameful, stupid, powerful iron-clad law was fettering him, sending him fettered to a stupid death.” In spite of honour’s stupidity, if he wants to remain a part of the community, he has no choice but to submit to it.

The ordinary citizens, who live outside the officers’ world, see things as perhaps they really are. “The officers went about like incomprehensible worshippers of some remote and pitiless deity, but also like its gaudily clad and splendidly adorned sacrificial animals.” We do not even see the duel, we only hear its result as Trotta does – second hand. Just as did Effi Briest, The Radetzky March makes duelling into something pointless, depriving it of its romance. Roth skilfully weaves both hope and despair into the final hours before the fight, and even with that the final result still surprised and shocked me. Honour, Roth shows, is something insidious as well as something obvious. It can lead to duels and avoidable deaths, but it can also be responsible for a coldness between family, where really there should be warmth.

Decay

Is honour the source of the decline of the Hapsburg monarchy? I don’t think that Roth suggests that here. Things are more complicated than that. After the duel, Carl Joseph is forced from his prestigious cavalry regiment into the infantry and posted to the Austro-Hungarian border with Russia. I loved the description of the nature there, of how the Austro-Hungarians “sacrificed” gravel year by year in trying to force the swampland into roads and solid ground. Here Carl Joseph meets a Polish Count, Chojnicki, whose pessimism about the Empire’s prospects is unconcealed. Chojnicki, however, sees a solution to the decline, and that solution is violence. He is a dark prophet of reaction. In killing its rebellious elements, there’s a chance the Empire may yet survive.

Back in Moravia, the district captain also witnesses changes as The Radetzky March progresses:

“At first he had merely belittled the nations that demanded autonomy and the “working people” who demanded “more rights.” But gradually he was getting to hate them – the carpenters, the arsonists, the electioneers.”

He does not think that the Empire is ending, but he knows that it has enemies. His transition, as the novel goes on, from benign governance to hatred, is perhaps a better starting point for thinking about the Empire’s decline. Like many others, he is unable to understand why Hapsburg subjects would have any loyalty to anyone other than the Empire and Emperor. His closemindedness, which has made him an excellent bureaucrat, leaves him unable to read his times.

Chojnicki is the borderland society’s leader, and Carl Joseph visits him regularly. With nothing else to do, and grieving for his friend, Carl Joseph takes up drinking. And now the Empire’s decay is coupled with his physical decay.

Blood

We have a chance to see Chojnicki’s theories in action. Carl Joseph is tasked with putting down some striking workers, with violence if necessary. He does not question his orders. “It had not yet occurred to the lieutenant that the workers were poor wretches who could be right.” Carl Joseph’s mind, like his father’s, has been conditioned to serve without questioning. But shooting civilians, even unruly ones, is far less noble than the fate he had once believed would be his. As he prepares to give the order to fire, he tries to imagine what his grandfather would have done. But he cannot. He is living in an unheroic age, and he no help comes to him. Instead,

he saw the times rolling toward one another like two rocks, and he himself, the lieutenant, was smashed between them.

The incident needs to be hushed up. People have died. But for Trotta the memory of that day remains with him as a time when he was powerful. It is a dangerous memory. As Carl Joseph’s decline continues, he gets drawn into gambling debts as a co-signatory to friends, and when the original debtors are unable to pay for various reasons, the creditor, Kaputrak, comes to Carl Joseph instead. Carl Joseph feels powerless before the man, even though he is an officer and the other a mere civilian. Unable to control himself, he grabs his sabre and forces the other out of the room with it, nearly stabbing him in the process. But there is a witness, and all Carl Joseph achieves is a little more time before he has to pay. Without war to give an outlet to his trained violence, Carl Joseph ultimately turns it against others.

The Little Things

What makes The Radetzky March so good is its subtlety. Little things, little ironies, pile up throughout the novel. Towards the end, there are more and more images of clocks and watches, pointing to the limited time left for Austria-Hungary. Then there is the use of music. The “Radetzky March” was a kind of unofficial anthem for the Empire, a tune the boy Carl Joseph used to hear each Sunday, is replaced by the “Internationale” as the workers begin fighting for their own corner, instead of blindly submitting. And then we have the use of portraits. Carl Joseph is haunted by the image of his grandfather, hanging in his father’s house. It represents his obligations to live up to the family name, and he comes back to it again and again.

But there are also portraits of the Emperor too. Early in The Radetzky March Carl Joseph removes one such portrait from a brothel, ashamed to see it there. By the end of the novel, however, the portraits, which once hung all over the Empire, have disappeared, stowed away now that other causes have grown in popularity. The situation with the portraits, as with the Trottas themselves, represents the state of the Empire. When they are taken down, the end is not far off.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed The Radetzky March. It is an extremely rich book, filled with irony and thoughtfulness. Roth treats Austria-Hungary neither as an ideal world, nor as a complete disaster. Within the all-encompassing idea of honour, he finds both good and bad. When he writes that, “all in all, Lieutenant Trotta’s experiences amounted to very little”, there is more than a hint of sympathy in the condemnation. Carl Joseph has been brought up rigidly, in a rigid world, and when he is forced to face things he hasn’t been prepared for he (understandably) falls apart into drinking and violence. If the Empire had not been heading for collapse, perhaps all would have been alright. He would have found a place in the world for himself. But history did not give him that choice.

In some way The Radetzky March contains a lot of what makes Tolstoy so good. Roth describes a wide range of characters from various social strata, giving the impression that he understands the entire world. In The Radetzky March even the Emperor himself is a character, which was pretty cool (Tolstoy does the same in Hadji Murat). But Roth is not quite as good as Tolstoy at making characters, and this is especially obvious with the female characters. For the most part they were boring seductresses, serving to demonstrate the Empire’s moral decline. Of course, given the story is mostly about officers, there’s little space for women to have a big role. All the same, I’d have liked to see a bit more variety. Tolstoy, for all his views on women, was definitely a lot better at writing them.

The Radetzky March is a great book in spite of both the women and Roth’s occasionally confusing chronological signposting of events (Roth doesn’t always link the chapters very clearly). It is an insider’s account of the decline of an empire, and a timeless story of the way the generations can fail to connect with one another.

For more about the tension between honour and practice, Effi Briest is worth reading. To look at another world that has faded away, read my review of Salvatore Satta’s novel, The Day of Judgement. For more Roth, I’ve written about Job: The Story of a Simple Man, here.