Oh, how wonderful it is to be young and happy, rich and idle. Such is, in some sense, the first impression I got from the French writer Boris Vian’s novel, Mood Indigo (after one of its film adaptations), originally translated as Froth on the Daydream. The work is absurd, and at first glance meaningless – people hop on clouds, the sunlight makes pleasant sounds. For the first third of the book I had thoughts of dropping it and getting on with something serious. Who actually likes to read about happy people? Certainly not me. And especially when that happiness is located in a world of absurdity, where nothing seems to matter or have a connection to our own world… in short, the book started to annoy me.

But Vian is playing a game in Mood Indigo. His characters are indeed happy, their world is indeed absurd. But this is just the setup. Because soon enough, a rot appears under the joyous façade, and all that was wonderfully absurd now becomes terrifyingly absurd, and the initial messages the book trumpeted now struggle to sustain themselves once things have started going wrong. And they go very wrong in this book. In the end, Mood Indigo moves on from its silly initial impression to become a brilliant reflection on mental health and more.

Our Colourful Cast of Characters

The silliness of Mood Indigo is in evidence from the very first words – “Colin finished his bath”. It is a meaningless phrase; its lack of drama subverts our expectations for what an opening line normally looks like. Our hero, Colin, is joined by Nicholas the butler and cook, Chip his friend, and Alyssum and Chloe to make up our main characters in Mood Indigo. They have silly names and lead silly lives. Colin has a lot of money and does nothing all day except enjoy himself. His world is yellow – the colour of positivity, of energy. Sunbeams flood his house with joyous sounds (as part of the way everything is connected in Mood Indigo, even normally soundless things all make noises).

The overall impression, come to think of it, is similar to a children’s television show. Colin not only eats strange things, such as an eel found in his sink, but he also has a huge store of Rube Goldberg machines, including a drinks mixer that doubles as a piano. Everything is possible in this world, and everything is positive. Colin’s great anxiety is over finding himself a girlfriend – both he and Chip are in their early twenties. Other than that, we might say that “life is but a dream”.

Things Go Wrong

Until it isn’t. At a party Colin meets a young lady, Chloe, and falls in love with her. His courtship of her is, as with everything else, an extreme affair – the world reforms itself to suit his new mood of infatuation. He finds that a “street led straight to Chloe”, and when they are together they can literally step onto clouds to enjoy themselves. In a moment of kindness Colin gives Chip part of his fortune – Chip doesn’t have money of his own – so that Chip can, in his turn, marry Alyssum, another friend of theirs. In the meantime, Colin and Chloe celebrate their marriage. It’s a wonderful, expensive, lavish affair – Vian enjoys describing everyone’s clothes in Mood Indigo – marred only by the sudden death of a music conductor when he falls from his perch in the church. But we don’t pay such things any mind. Death doesn’t bother us.

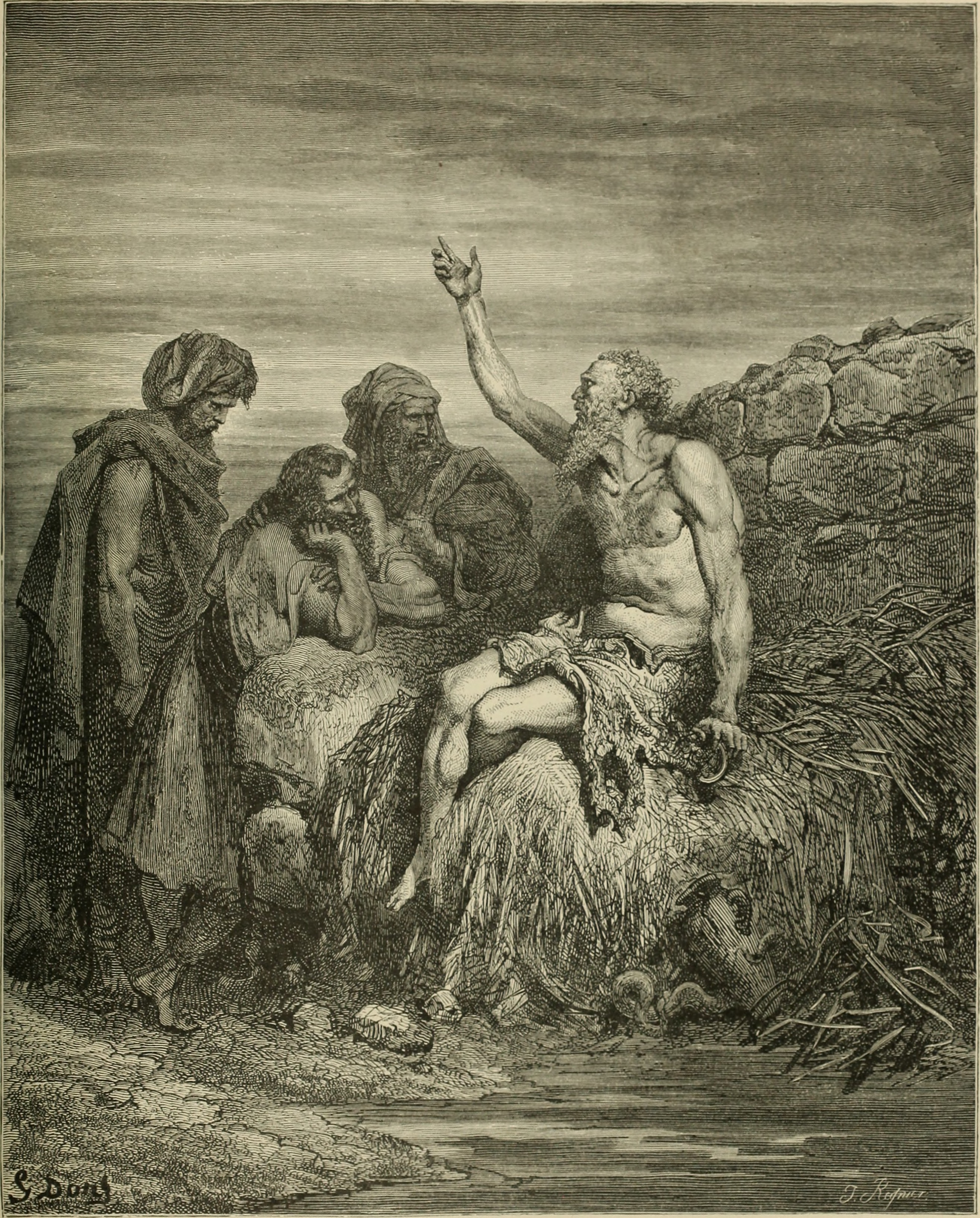

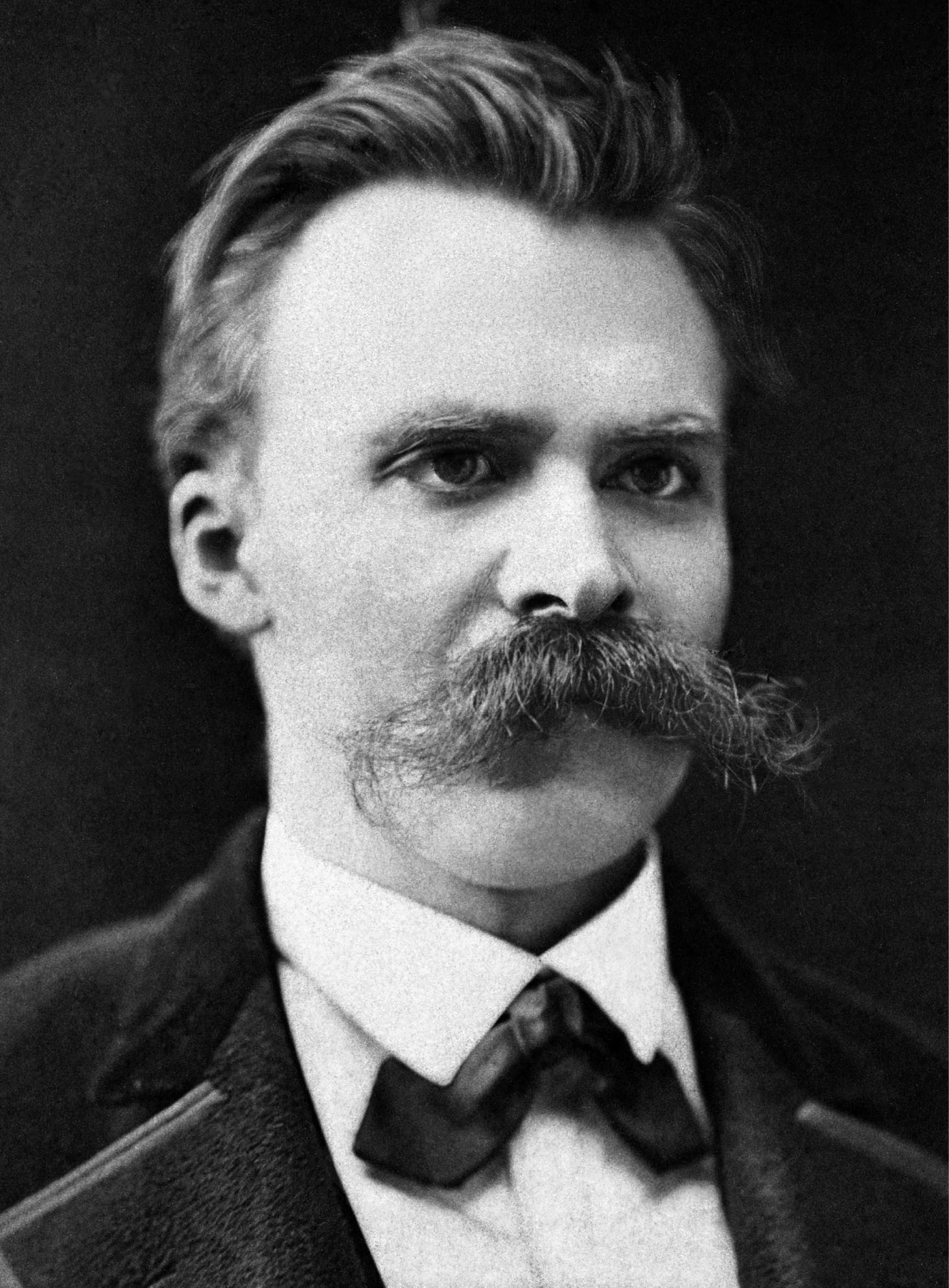

On their honeymoon Chloe begins to get sick, and it is here where Mood Indigo becomes really interesting. At first it’s a sickly, overly happy story about young love – but now darkness begins to creep in. Chloe has a disease of the lungs. There is a waterlily in her right lung, and the only way to save Chloe is to surround her by other flowers in the hope that they will scare the waterlily away. It is not a cheap affair, and Colin spends more and more of his money in trying to save Chloe from her illness. But nothing seems to have any effect, and soon Colin finds himself running low on funds and forced to find work for himself. Meanwhile, Chip and Alyssum’s relationship is also under strain – Chip hasn’t used Colin’s money on the wedding, as planned, but on his obsession with the writer, Jean Pulse Heartre, instead.

Objects and Objectification

Chloe’s illness, and Chip’s increasing obsession – he spends his money on everything possibly connected to Heartre, from books to old clothes the writer might once have worn – both mark the novel’s decline from its cheery beginning into gloom. Both of these events are also important because the decline in Mood Indigo can be partly explained as stemming from its treatment of people and objects. What I mean, is that in some way the novel is an argument against objectification, overt and covert. We can think about this through the example of Chloe’s illness. Chloe’s personality is pretty non-existent in Mood Indigo. She is simple, concerned only with objects – at one point she says she wants to buy: “things and things and things”. Every time she is described its by reference to her beauty – at first this annoyed me, but now I see it was deliberate.

“Chloe’s such a pretty girl,” one character says of her. “I can’t imagine her being ill.”

Chloe is treated like an object by everyone around her, and in a way it kills her. Colin loves her, but the treatment she gets is all through objects – in the end, she is left fading away on a bed, surrounded by plant pots. It is a strange image, but a striking one – she is literally being destroyed by beauty. Chip’s case is similar. In his obsession with objects connected with Heartre, he neglects the human he is supposed to love – Alyssum. All of the girls in Mood Indigo, by the way, have names connected with flowers (Chloe is from the Greek word for fertility). And like flowers, the girls are left to blossom and then die, without the water of true affection. They are never treated like people, like individuals with personalities.

Money and Emptiness

Connected with objects is the way money is used in Mood Indigo. At first it seems to be a source of liberation for Colin, letting him do whatever he wants. He goes ice skating and kills people (by accident) without facing any consequences. He goes to parties and meets pretty girls. The characters of Mood Indigo seem to enjoy the fullness of youth. Chip, when he gets Colin’s money, is able to pursue his passion for Heartre without any limits. Chloe is able to buy all the things she wants. But as Mood Indigo continues the emptiness of their lives becomes harder to avoid.

Chloe’s things are worthless once her illness takes hold, and Chip’s passion soon morphs into an addiction, excluding everything else in his life which once he had valued. Finally, as soon as Colin’s money starts running out, his entire house and world begin shrinking, growing dark and unhealthy in reflection of his inner state. By spending, by not paying attention to the consequences of their actions – most noticeably they random deaths of the early parts of Mood Indigo – the characters avoid trying to grow, to develop themselves or find a real and lasting happiness.

Conclusion

It is a wonderful thing to be young, to be rich and live irresponsibly. At least it seems so, while it’s happening. The horrors of the world, its terrifying absurdity, barely affect us or our happiness. Mood Indigo perfectly captures that mood of joy. But the novel goes further, in showing us that under our pleasure there lurks someone else’s pain, that the happiness we think we have is often bought at the price of someone else’s. Ultimately, happiness comes in part from choosing not to see the world. During Chloe and Colin’s honeymoon, at the last stage of Mood Indigo’s “happy part”, Chloe finds herself unable to look through the window of their car onto the world outside – the sight is too distressing. Fortunately, there is an easy solution. You can just put a filter on the window, see only what you want to see, and everything will be okay.

Ultimately, Mood Indigo is about the dangers of easy solutions, of turning the world into your playground, of treating others as objects and shirking responsibility. You will have a great time, at least at first. But soon enough something will happen that you could not have predicted – like an illness – and you will find how little you are prepared for the world hiding behind your dreams. I wasn’t expecting to like Vian’s novel, but I did. It’s intelligent, fun, and has much more to say than I have written about here. I’m grateful to my girlfriend for recommending it.

The title of Mood Indigo comes from a piece by the legendary (and repeatedly namedropped in Mood Indigo) jazz artist, Duke Ellington. Here’s a version on Youtube.