When I wrote about Aliss at the Fire, I wondered whether it had now become necessary for anyone wanting to write stories about faith and religion to adopt a style like Jon Fosse’s. A style that shifts constantly, fluctuating between perspectives and making porous limits which normally seem solid. One feels adrift within a more mystical world, where God and faith are not idle thoughts but lived experiences. Now, having finished Fosse’s much longer Septology, I wonder whether I can even write a blog post about it without adopting the same style, which here reaches still greater heights of mystic power, and letting my sentences run and run, and my entire language become like a breath, going in and going out but never, except at the end of the post, finally ceasing.

I will spare readers such an attempt. Instead, I will try to say a few words about the book. It is hard. Normally, if I like or dislike a book, I will annotate it heavily. My Septology has been only lightly touched, mainly just with marginal notes indicating what scene we are in. I underlined only a single phrase. This gives some indication of some of the strangeness of the text, which has no full stops and lives by commas, ands, and paragraph breaks. Much of the narrative here is mundane, repetitive stuff, the kind we might know from Samuel Beckett or Thomas Bernhard – a character’s struggle to persuade themselves to get out of bed or open the door. When moments of great beauty or significance arrive, they are entire paragraphs of reflection which gain their power by accumulation and contrast, and which whither and die when we try to extract them.

Septology concerns a painter called Asle, who lives in the Norwegian countryside. He has a friend, almost a double, also called Asle, who lives in Bergen and suffers from alcoholism. There is another double-like figure in the form of Asle’s wife, Ales, who died some time ago of a mysterious illness. Other characters include Beyer, a gallerist, and Asleik, a farmer. There is also a somewhat sinister woman called Guro, who has her own double too. Our narrative is mostly of reflection. The first Asle is our narrator, and he uses the first person, but when he reminisces or transports himself to the life of the second Asle, he uses the third person, even if he seems to be thinking of his own past.

Over Septology’s seven books narrator-Asle goes to Bergen several times, discovers his friend Asle passed out in the snow and takes him to the hospital, delivers some paintings to Beyer, has an artistic crisis and decides not to paint anymore, and decides to visit Asleik’s sister for a Christmas meal. But mostly he ruminates. As in Aliss at the Fire, Asle seems to see into his doppelgänger’s soul. He also sees into his own life’s story, seeing figures as he drives past the places of his past, and in such a way that we cannot know whether he falls into their world, or whether they emerge back out into his.

Asle is not the other Asle. But they are almost one another, being both artists, both being bearers of the same name. Yet what is the meaning of this? Fosse is careful with names. Streets and restaurants are given simple names like “The Lane” or “Food and Drink”; so too are people – “The Teacher”, “The Bald Man”, and so on. One effect of this is to give every encounter a heavy sense of symbolism and significance, even if we cannot always identify at first glance what that might be. The second Asle, when met for the first time in a memory, is “The Namesake” – not the same, but bonded to him, nevertheless.

When I really think hard about Septology, I can say that it is a book of suffering. And the two Asles are part of this. They have led divergent lives, with a common root in their art and countryside upbringing, and the split occurring when it comes to the matter of love. Narrator-Asle meets Ales by chance in a café in Bergen, and immediately they fall in a kind of magical, dreamlike love that seems to last until her death. The other Asle arrives in Bergen to go to The Art School there with a girl already following him, pregnant with his son – The Boy. He marries her, but within a year has already found someone else, Siv, a woman who studies at The Art School and who seems to offer a more fulfilling relationship than the suicidal Liv. But like the names, the relationships echo, and it seems – seems, because nothing in Septology is quite certain – that Asle is then unfaithful towards Siv with another woman, Guro, and Siv leaves him too.

A harmonious home life, versus a chaotic one. But both are marked with tragedy and ultimate loneliness. Both Asles drank heavily when younger, but Ales’s Asle gave up – under pressure from her – whereas the other Asle did not. Early on in the novel we are faced with shocking images of the second Asle, “weighed down as he is now, so weighed down by his own stone, a trembling stone, a weight so heavy that it’s pushing him down into the ground, I think”, as he struggles even to get up to pour himself another drink. His life has completely collapsed with the breakdown of family life, and his thoughts seem to circle around suicide.

The other Asle has also seen his life collapse. The love he has for Ales is so pure, so total (in a novel with much German, Ales’s similarity to Alles – “everything”, cannot be entirely coincidental), that her loss leaves her own Asle with deep, deep wounds too. He lives alone, he lives in the countryside, with barely a friend, and now his heart’s companion is gone. Though years have passed since then, the wounds remain.

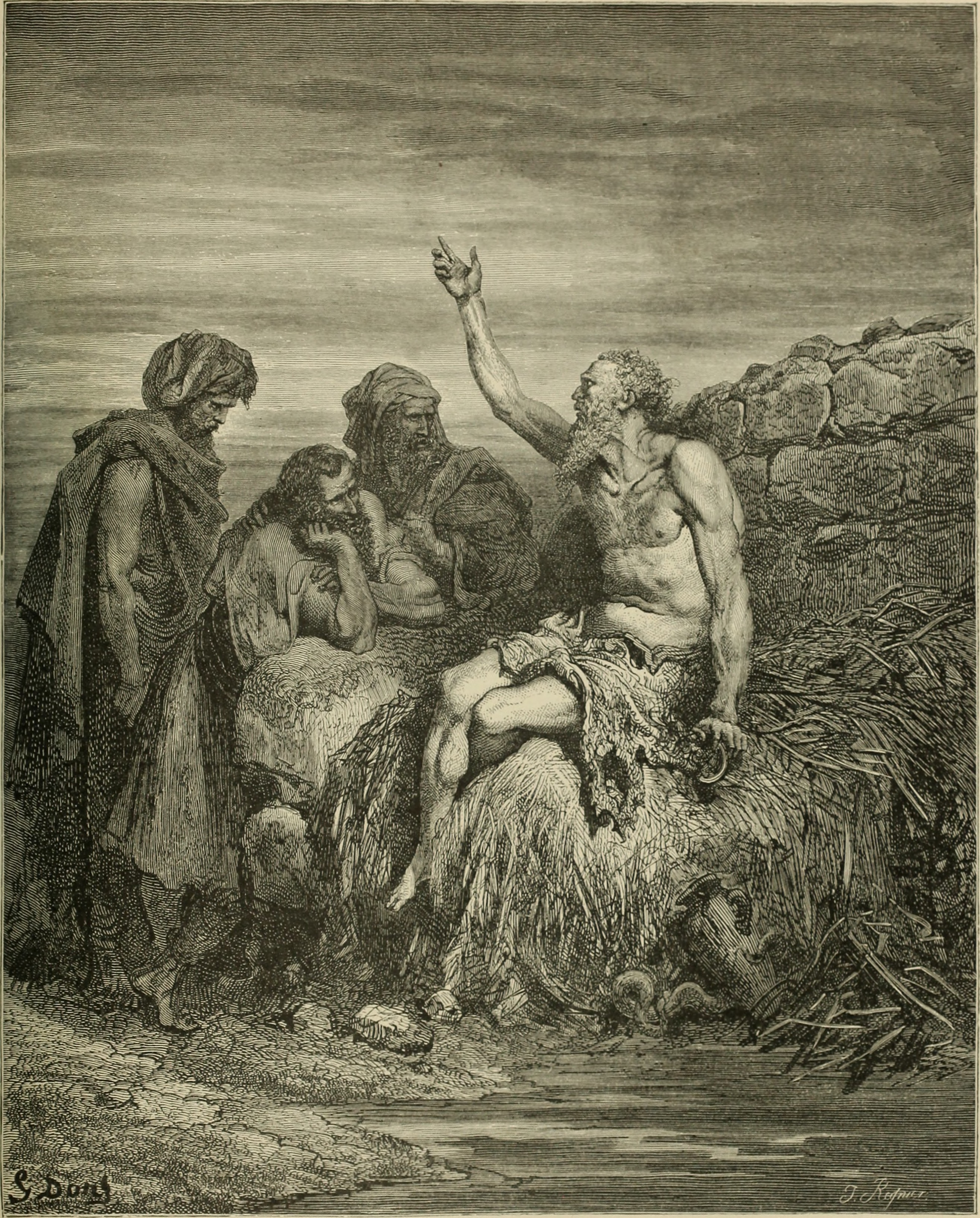

But still our narrator survives. He does not return to drink, he does not end his life. The reason is, without a doubt, his religion. Septology is a novel about faith’s ability to be a fortress that can protect us from the greatest injuries. Faith is this novel’s foundation and its source of power. Each of Septology’s seven sections begins with art, but each ends with Asle in prayer. Whenever he is in pain – and he often is, thinking of Ales and his loss – he takes his rosary and prays. The Our Fathers, Hail Mary’s, and Christ Have Mercy’s, stabilise him and help him cast off from the world when he needs to sleep. Because his life is so full of pain, these moments in the text feel fair and earned. Religious or not, we see that these moments are necessary – utterly vital and necessary – for Asle’s own survival.

For the survival of pain is this story – not its complete defeat. We notice that for all the memories we encounter, Septology is also full of silences. Asle mentions, without remembering, the end to his drinking. And in truth aside from its beginning, the relationship with Ales is also a blank. We have to take on faith that the relationship was what he claims it was. Often Asle thinks of Ales and then says he doesn’t want to think about her, that the pain is too great, so that these blanks remain. We notice, sooner or later, that Asle’s memories of the boy Asle are indeed usually about himself. But making him another, not the “I”, seems itself a way of hiding past pains whilst approaching past realities.

God is also present in the silences. Asle feels God, just as he feels Ales’s presence, and seems even to see her at times. The flowing prose of Septology allows for this, just as it allows the whole text to seem, at times, like a breath or a prayer. Asle’s art draws him close to God, as does his contemplation of Ales – who had introduced him to faith to begin with. Septology’s world is full of pain, as is that of Aliss at the Fire, so that as with that work God becomes a necessary force – the only way of not falling into despair. A child drowns, a sister dies suddenly of illness, as does a beautiful friend – and many other characters suffer similarly upsetting fates. But we see here, unironically, what it might mean to commend the spirits of the departed to God – and what solace we might find in those words.

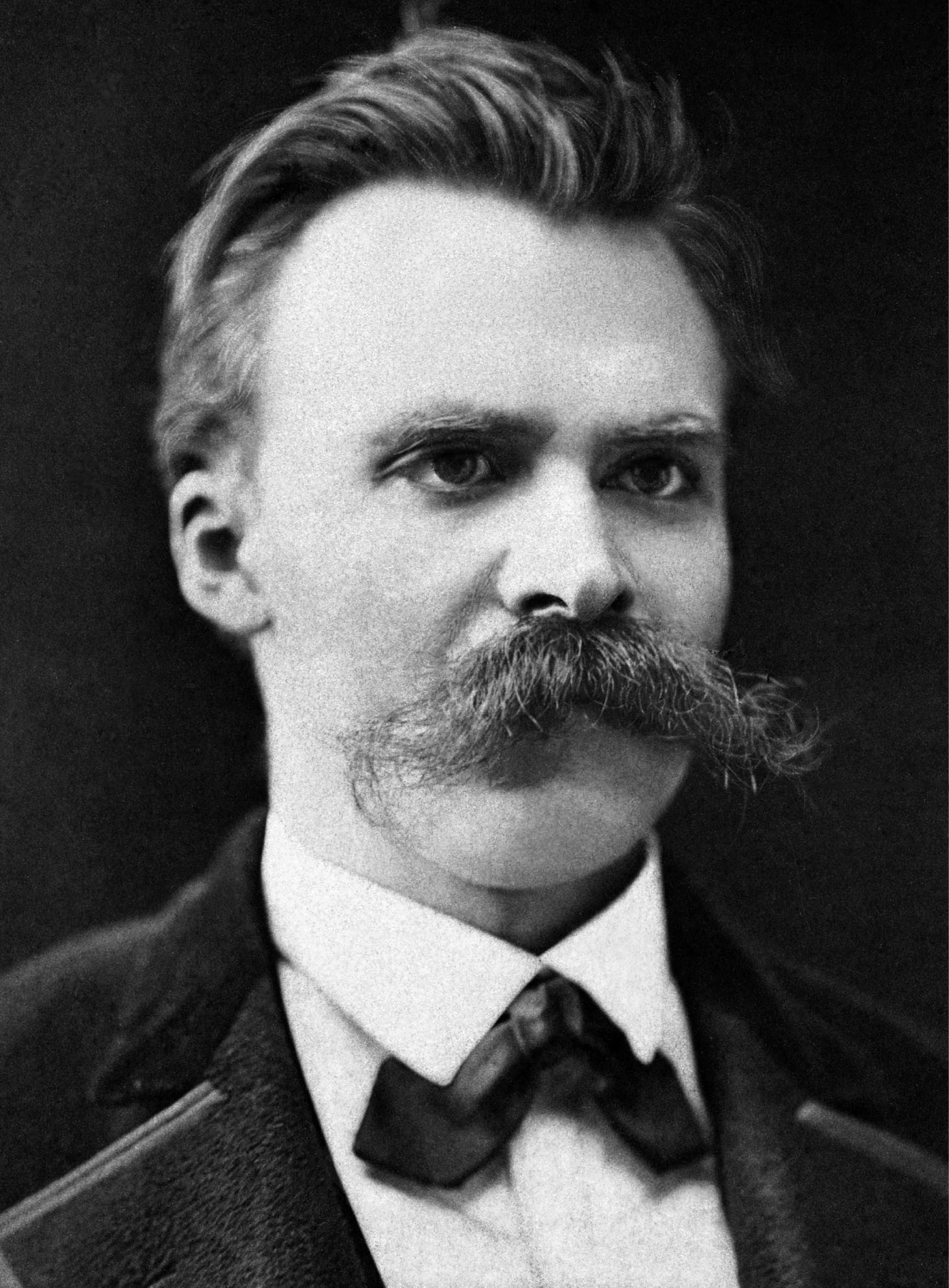

Ultimately, what Septology does is argue for the power of faith as well as any apologist could, perhaps better. Religion is proved, if ever, by experience, and Septology draws us into an experience which shows faith’s potency in that specific life – and, in the second Asle’s case, the damage of its absence. We see something similar in my other favourite religious writer, Marilynne Robinson. Both writers, Fosse and Robinson, are adept at making a reality that is sanctified and filled with wonder. Fosse’s difference is that it sometimes seems we are relying on Asle’s consciousness to make his reality so, whereas in Robinson’s works life really does seem to be invested with God’s reality. By this I mean that her language constantly confirms God’s presence, whereas Fosse’s language confirms God only at particular points, for a particular consciousness. That means that stretches of Septology can be quite dull and meandering, as we wait for that moment where we will feel significance and harmony again.

Such an approach would most aid a story showing a wavering, on-off faith. But that’s not really what’s going on here. It’s just that Asle is remembering something, and we need to work to make it meaningful for ourselves, if we can. If sometimes it can feel like this is not worth the effort, that shouldn’t take away from the rest of the book. Septology is a work of contrasts, of light and dark, faith and the loneliness of its absence, and it may be that its magnificent, truly heavenly highs are dependent on the moments when the story is simply a limited low. Really, truly, it’s a marvellous book regardless.