Immensee is perhaps the best known of Theodor Storm’s novellas, and like many of them it is a tale of thwarted love and missed opportunities. Unlike Storm’s Aquis Submersus, which I have written about here, and which is characterised by elements of tragedy and drama, Immensee is a much more symbolic work where the main focus is on “Stimmung”, or mood. What follows is a summary of the story of Immensee, followed by some ways of looking at the meaning of the tale. Translations from the German are mine.

The Plot of Immensee

Immensee tells the brief story of two children, Reinhard and Elisabeth, who at first seem destined to marry. Through ten vignettes, each no more than a few pages, we follow the two as they grow from children into adults, and then become separated through Elisabeth’s marriage to another man, Erich. The opening and final vignettes, both titled “The Old Man” are set considerably later than the rest of scenes, and show Reinhard as an old man, lonely and unfulfilled as he reminisces upon the disappointment of the past and his own role in sealing his fate.

The first of the reminiscences is entitled “The children” and shows the two children – Reinhard aged ten, and Elisabeth only five – playing together in the height of summer. Their joy with each other is palpable – they dance and sing, and the section ends with them returning home, “springing hand in hand together”. The next section, “In the Forest” takes place seven years later, as Reinhard is preparing to leave for further study in a different town. The two children are tasked with locating strawberries and Reinhard claims he knows a place, but when they arrive, exhausted, it is dark and there are none left on the bushes. A brief division is seen between the children, as Elisabeth says the place makes her afraid, while Reinhard talks of its beauty. In either case, they leave empty handed, and Reinhard’s final day is a disappointment.

“There Stood the Child on the Road” sees Reinhard already at university on Christmas Eve. Like a good student we find him drinking in a bar, where a gypsy woman is playing music. Reinhard stands and makes a toast “to your beautiful, sinful eyes!” and tries to give her money, but she rebuffs him when he refuses to stay for her. He leaves the bar and goes outside onto the street, and then home, where he finds a gift of cookies from Elisabeth has arrived. In her letter she berates him for not having written or sent her any fairy tales as he had promised. Overcome with guilt, Reinhard goes out and buys a coral cross for her, and then begins writing letters home to her and his mother.

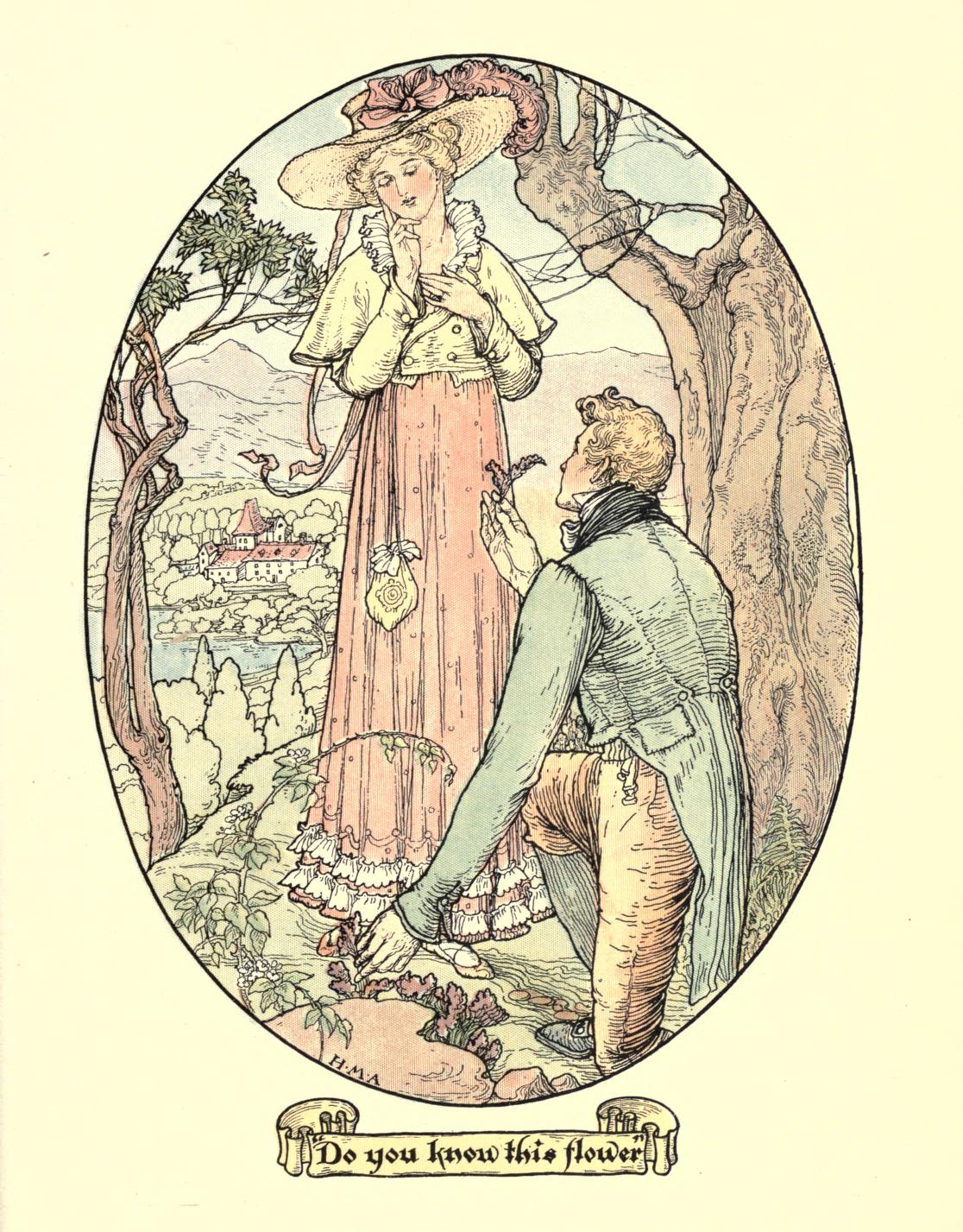

“At home” sees Reinhard home and with Elisabeth, but he finds her changed. There are pauses where earlier there would be conversation, and she often turns her back to him. He also discovers that in the place of the bird he had sent her another boy, Erich, has given her a luxurious cage with a canary inside it. She doesn’t seem interested in what he has written either. But before he departs, he seems to rekindle his passion for her, and reassure himself of her faithfulness. He tells her he has a secret, “and when in two years I am back here you shall learn what it is!” – undoubtedly a proposal. But in “A Letter”, the shortest of the vignettes of Immensee, we learn that Elisabeth has agreed to be married to Erich, after refusing for some time. Reinhard, perhaps to build expectation, hadn’t written to her since they parted…

“Immensee” has Reinhard come to Immensee, the estate that Erich has inherited and which has given him the means to win over both Elisabeth and (more importantly) her mother. He has come at Erich’s invitation, not his wife’s, because Erich wishes to surprise Elisabeth by showing her her old friend. And for most of the scene we don’t even see her. When Reinhard finally does, she appears unfamiliar, as “the white and girlish form of a woman”. Both of them appear changed to one another, and Reinhard ends up starting to go for walks alone in the evenings, where on one occasion the heavens break open and he is soaked.

“My Mother Wanted It” has the family – Erich, Elisabeth, and her mother – sitting around one evening with Reinhard also present. Together Elisabeth and Reinhard sing a popular Romantic ballad, and then, emboldened, Reinhard reads one of his poems – he is a writer – which is clearly about Elisabeth’s marriage to Erich and her loss of Reinhard. She grows embarrassed and leaves the room. Reinhard also goes outside, and approaches the lake that lies in the centre of the Immensee Estate. There he sees a white lily, and he tries to swim out to it. He gets very close, but is unable to make it to the lily. He leaves, sodden and disappointed.

In “Elisabeth”, the final vignette, Reinhard tries to reminisce upon the past together with Elisabeth, but she rejects him, even the idea of going looking for strawberries – “it’s not the time for strawberries now”. Having failed, Reinhard heads back to the house. On the way he meets the gypsy, now an old woman, who asks for alms. He gives her his money and then asks her what else she wants, but she says there’s nothing else. At the house Reinhard finds he cannot write anymore and decides to leave as soon as possible. The next morning he aims to leave without notice, but she finds him in time to confirm her suspicions that he will never come again. And then Reinhard is gone.

His memories exhausted, the aged Reinhard sees before him the water lily again and decides to get to work. His creativity is gone, but there remains within him a capacity for academic study. This is to be his fate.

So that’s the plot of Immensee. Now for a few bits and pieces towards thinking about it.

The Novella’s Structure: Poetry and Vignettes

I mentioned above that Immensee is divided into ten vignettes, or scenes, ranging from Elisabeth and Reinhard’s youths up to Reinhard’s old age. What is the significance of the structure? Each of the scenes is able to function as an independent unit, similar to separate poems in a cycle. Each scene brings with it a different mood, with its own symbols and ideas. They function as separate memories, while nonetheless forming part of a coherent whole – Reinhard’s understanding of his failed relationship with Elisabeth. The containment of these scenes within Reinhard’s memory serves to contain his central despair over his failure and bring order to the meaninglessness and chaos of his life. By organising his memories Reinhard can come to understand them and move on. The novella thus moves from the first scene’s initial pain at being reminded of Elisabeth, to Reinhard moving on through academic work at the end.

By using vignettes and focusing on the mood, the structure of Immensee has significance outside of Reinhard’s perspective too. Not only does the structure bring order to Reinhard’s life, it also makes it beautiful. In this way Storm takes what is ultimately a tragic story and imbues it with a redemptive quality – he makes it into art. In this way, he predicts Nietzsche’s command that our suffering must be made into art so that it can have value.

Immensee also makes use of poetry. Storm was a wonderful poet as well as a writer and a few of the poems in Immensee are also found in my collection of his poetry. The use of poetry serves to enhance the feeling that the vignettes are poetic themselves. The song of the gypsy is important because it stresses the fragility of existence, warning Reinhard of the danger of his hopes for Elisabeth and his ultimate fate.

Today and just today,

Am I so beautiful.

Tomorrow, oh tomorrow,

All this will pass away.

And only in this hour,

Can I call you my own.

For death, alas my death

Will find me all alone.

The poetry that Reinhard reads to Elisabeth is also significant. Reinhard thinks, perhaps, that the beauty of his artistic talent will be enough to win the old Elisabeth back to him. But he is sorely mistaken. In this way we see that poetry and the artistic structure of Immensee more broadly is designed to redeem the world but not grant us riches in it.

The Symbols and Details of Immensee

Immensee is full of symbols and symbolic content and here I’ll only focus on the things that strike me as particularly significant. After all, our essays are only so long.

Colours, Light and Dark. According to my notes from the first time I read Immensee the colours of the novella get progressively darker as it progresses. Reading it through this time, I don’t think it’s an exact science. Nonetheless, there is a clear movement from light to dark. When the children are first playing it is summer and bright outside. But by the time of their first problems, in the forest, it is dark. Immensee itself, for Reinhard at least, is marked by its darkness. The weather there is always bad and stormy, reflecting his own increasingly sad state of mind.

Names. I’m not sure what the significance of any of the characters’ names in Immensee is, but there is one point I’d like to mention. In “A Letter” we learn that Reinhard’s second name is Werner after his landlady brings in the letter from Elisabeth’s mother. It is something of a jarring moment for the reader, as up till then Reinhard has only been called Reinhard – we come to know him by that name. It is significant because it reflects the jarring nature of the news the letter contains: the person Reinhard thought he knew, Elisabeth, has changed completely from his idea. The intimacy they had shared is lost, and Reinhard thus becomes (albeit temporarily in the text) Mr Werner. But it is enough.

Immensee itself is also a significant name. “Imme” is a poetic variant of the German word for bee, so the estate’s name is something like “bee-lake”. Bees are used throughout literature for their associations with productivity and hard, collective work. This is exactly what we see on Erich’s estate: a world of practical achievements in his factory and workers that stands in complete contrast to Reinhard’s unacknowledged, intellectual world. So in its own way, even the novella’s title is there to show what Reinhard lacks.

The Bird. Reinhard sends Elisabeth a linnet, a small bird. But the bird, we learn in “There Stood the Child on the Road”, has died. And when Reinhard goes home he sees a new bird, a canary, in a new golden cage. The cage represents the riches of Erich, having inherited the estate at Immensee, and perhaps the bird in the cage may be read as Elisabeth herself, her heart now caught by another. In any case, the incident with the birds shows clearly how Reinhard’s role in her life is being usurped by another.

The Coral Cross. The significance of the coral cross seems to me rather to be its lack of significance to the plot. In a work full of echoes, symbols and connections the cross is notable in that it does not reappear, but rather is forgotten. The faith that the cross implies turns out not to be present in Elisabeth – or at least, the faith is eventually overcome. It is, in a sense, a red herring among symbols because of its lack of use. Instead, it comes to symbolise Reinhard’s failure.

The White Lily. This is the main symbol of the whole of Immensee. It appears both in “My Mother Wanted it” but also in the final vignette, as a vision before Reinhard’s eyes. Reinhard swims into the centre of the lake to try to capture the beauty of the lily, but he is defeated. And thus it comes to represent all that is unreachable, unattainable, especially in terms of beauty. But at the same time, its beauty is great, and thus when Reinhard thinks about it towards the end of the novella it comes as a sort of consolation. It cannot be reached, but it remains in his memory, just as Elisabeth herself does.

Ways of Approaching Immensee: Romanticism and Social Constraints

There are lots of different ways of approaching writing about Immensee and here are those that caught my eye while thinking about the novella.

Parent-child conflict. How very banal. Nonetheless, there is a social angle to the novella that’s well worth exploring. Elisabeth is put under a lot of pressure by her mother to be with Erich, rather than with Reinhard. The reason for this seems to be that Erich is far more monetarily successful and has a greater social status, while Reinhard is simply a writer. When Reinhard comes to visit Immensee, Erich shows him all of the industry being built on the land, including a spirits factory. Reinhard, however, ends the novella still renting rooms, rather than owning houses.

Reinhard’s failure to be with Elisabeth is the result of his reluctance to tell her his feelings outright – instead he wants to wait too years before surprising her with a proposal. But Reinhard’s failure is also the failure of the Romantic sensibility more broadly. Immensee, in the version we now read, was published in 1851, some time after the Romantics of the German lands, such as Heine, had already given up on Romanticism or died. The novella is far enough beyond Romanticism to treat its ideas with scepticism and irony.

This attitude manifests itself in the way Reinhard is treated. He makes up fairy tales for Elisabeth and writes poetry, and seems to see great power in gestures and in art. But as a result, he waits to tell Elisabeth of his feelings, including making the ridiculous decision not to send any letters for two years, all of which means that Erich is able to propose instead. When, at Immensee itself, he comes to sing with Elisabeth, he tries to talk about his passion for the music, but nobody pays any attention to his lyricism on the subject. Reinhard, the Romantic, is out of touch and unable to communicate properly with the modern people surrounding him. His passionate verses fail to seduce or please Elisabeth – instead they only upset her. Immensee thus presents the collision of the Romantic sensibility with reality and its subsequent failure to impress.

No doubt the art is beautiful, as Immensee itself is. But it is also useless for Reinhard’s pursuit of his worldly aims. He needs money and status if he’s to get anywhere when he has a rival like Erich.

Conclusion

Storm’s novella has remained popular for over one hundred and fifty years, and given what I’ve discussed above I hope it’s possible to see why that’s the case. Not only is the work short and structured in a way that makes it easy to read a few pages of at a time, it is also highly symbolic, making it richly rewarding to read it repeatedly. Its clearly symbolic quality makes it prime fodder for classroom syllabuses, because it’s hard to find something in the work that doesn’t mean something. I would know about that – I first had to read it back in school, though I’m not sure I actually did, as my copy was eerily devoid of annotations when I came to read it through last week.

The topic of the novella also helps it. Frustrated love is something that is easy to relate to, and as a result the distance between Storm’s time and our own seems far less than it actually was. For who hasn’t found, in the course of their lives, some small regret for a relationship that could have been, if only we’d just stopped and had the confidence to act in time? A gloomy memory, no doubt, but at least in Immensee old Storm turns the sentiment into art. In a way, our sufferings are thereby redeemed.

For more Theodor Storm, check out my thoughts on Aquis Submersus here. For other German novellas, check out Meyer’s Marriage of the Monk, Eichendorff’s From the Life of a Good for Nothing or Thomas Mann’s Gladius Dei.

If you’re looking for a translation of Immensee, here’s one I found. If you want to read some of Storm’s poetry, I’ve translated some poems here.