What is attractive about Ludwig Wittgenstein is that he was a real genius. I did not gallop through Ray Monk’s Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius because I wanted to know about Wittgenstein’s philosophy – I did it because I wanted to know about the man. Wittgenstein’s thoughts on language are worth knowing about, sure, but certainly not near the top of the pile of philosophies I want to have a grasp of. Though Monk’s biography gave me some sense of Wittgenstein’s thoughts, the focus here was more on his life. This approach works because, for me at least, the parts of Wittgenstein’s thought that are most interesting are precisely those that came from his life – such as the way the mystical sections of the Tractatus came from Wittgenstein’s experience in the First World War.

Rather than summarise a summary of Wittgenstein’s thoughts, I thought I’d note here the parts of his life that struck me as particularly entertaining, saddening, or interesting. Being such a unique personality, Wittgenstein provides plenty of all three.

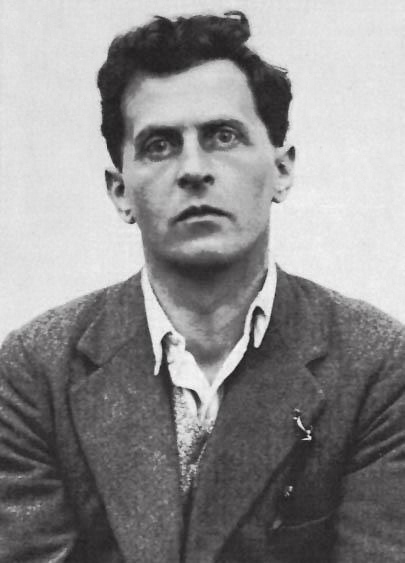

The Briefest of Biographical Summaries

Wittgenstein was born in Vienna to one of the richest of all Austrian families and had an extremely privileged upbringing. But the Vienna he was born into, at the tail end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s life, was not a happy place producing happy people. I counted at least five suicides in the first chapter of Monk’s book alone – three of them Wittgenstein’s brothers. Our hero moves to England for his studies, meets a number of philosophers including Bertrand Russell who all eventually come to consider him a genius. He spends time in Norway and as a soldier, works as a teacher and gardener, goes back to Cambridge to teach, helps out in the Second World War behind the scenes, and finally dies. Given that the lives of most philosophers are little more interesting than that of Immanuel Kant, who never left his province, Wittgenstein’s life of action is rather exciting.

Genius and its Duty

One thing making Wittgenstein interesting is that he was not a scientist and did not see philosophy as scientific. Instead, he approached philosophy creatively. At one point he shocked the boring old gits of the Vienna Circle of philosophers by recommending they read Heidegger and Kierkegaard. He also lectured primarily using the power of inspiration, standing in the lecture hall or else pacing until a thought came to him, and then announcing it to enraptured onlookers. Most importantly, Wittgenstein’s whole character was artistic. Monk quotes Russell here:

“His disposition is that of an artist, intuitive and moody. He says every morning he begins his work with hope, and every evening he ends in despair.”

At another point Russell had Wittgenstein pace up and down his room for three hours in silence before Russell finally asked: “Are you thinking about logic or your sins?” “Both,” Wittgenstein replies, and continues his pacing.

The language of sins is surprising to people who like me think of Wittgenstein as a boring logician. In reality, Wittgenstein was of a decidedly religious sensibility. His major influences appear to be Tolstoy and Dostoevsky – Hadji Murat and The Brothers Karamazov are just two of several books by the authors that Wittgenstein adored and passed out among his friends. Acquaintances compared him to Levin from Anna Karenina and Prince Myshkin from The Idiot. Though he was raised a Catholic, Wittgenstein did not believe in the Church’s dogmas, even as he believed in a kind of God and definitely believed in his own sinfulness.

Sin, for Wittgenstein (as it was for Tolstoy), was determined by his own conscience: “The God who in my bosom dwells”. What Wittgenstein feared most of all was judgement – “God may say to me: “I am judging you out of your own mouth. Your own actions have made you shudder with disgust when you have seen other people do them.”” He was never happy with himself. He expected nothing less than perfection from himself, that beautiful but impossible congruence between one’s thoughts and one’s actions. At one point he made a confession to all of his friends in an attempt to rid himself of his pride. Instead, he just annoyed them. Few were interested in listening to all of his minor failings.

But Wittgenstein believed that he had a duty to be perfect – the duty of genius that Monk uses as his biography’s title. By perfect I do not mean in conduct so much as in the sense of squeezing out of himself as much philosophy as possible, by any means possible. At one point Wittgenstein was struggling from overwork, but rather than take a break as his friends suggested, he decided to try hypnotherapy to help him concentrate even more successfully. At another point he decides to abandon the world to live in a hut in Norway and write philosophy.

Russell, ever sensible, warns him against it:

“I said it would be dark, & he said he hated daylight. I said it would be lonely, & he said he prostituted his mind talking to intelligent people. I said he was mad & he said God preserve him from sanity. (God certainly will.)”

Wittgenstein does not listen. He does not listen to anybody at all. In many ways he reminded me of Tolstoy, who like him was sceptical of doctors and medicine, and had an all-consuming desire to be perfect: “How can I be a logician before I’m a human being! Far the most important thing is to settle accounts with myself!”

And Wittgenstein is miserable as a result: “My day passes between logic, whistling, going for walks, and being depressed.”

As he gets older Wittgenstein mellows in some ways, thanks in part to his loves, male and female. The sheer obstinacy of his youth is less visible, and there is less of the humorous, if sad, determination to ignore everyone else’s opinions or suggestions.

The Dark Side of Genius

Wittgenstein’s perfectionist demands upon himself were ones that affected everyone around him, and rarely positively. He shows a remarkable lack of concern for others’ feelings and emotions, especially those of his partners. Even though when asked how to improve the world he declared that all we could do was improve ourselves, his attempts at self-improvement rarely seem to improve either him or the world. He loses friends at every turn – including Russell himself. His vaguely Tolstoyan ideal of a good life – working with one’s hands while developing spiritually – is not one he himself follows, stuck in Cambridge, but is one he forces on others, including Francis Skinner, one of his partners.

When Wittgenstein actually encounters “the common man”, said man rarely proves the best of us. Wittgenstein dislikes his soldierly comrades in the Austro-Hungarian army, and during his years of teaching in the mountains of rural Austria he ends up being a dreadful teacher for anyone lacking ability. Wittgenstein preferred to use fists to ensure mathematics got into his pupils’ heads, rather than patient and repeated explanations. At one point he even knocks a poor child unconscious, for which he is taken to court.

As for the intelligent people in his life, they are rarely treated by Wittgenstein to any greater kindness or concern. Of one friend he said: “he shows you how far a man can go who has absolutely no intelligence whatsoever.” When another writes to him, wishing him well in his work and social endeavours, Wittgenstein responds especially pleasantly: “It is obvious to me that you are becoming thoughtless and stupid. How could you imagine I would ever have “lots of friends”?” And indeed, after reading such a letter, how could we doubt his social abilities?

Wittgenstein’s determination to destroy himself in the name of perfection ruined any chance at happiness, even though he thought that perfection would be what would finally provide him with it. In this Wittgenstein is no different from many other depressed people, your blogger included, who set themselves impossible tasks and achieve nothing but their own misery thereby. I found one moment particularly amusing in connection with this. Wittgenstein finally sees a doctor for some exhaustion and pain he was suffering from and gets given some vitamins. Once he takes them, he immediately recovers and returns to work. Rather than lying in his moral failings, perhaps his inability to work could have just lain in his poor health. However, in his determination to see everything through the lens of his own sinfulness, Wittgenstein obviously never considered the possibility that he might just need to live a little more healthily, eat well and sleep.

Conclusion

Wittgenstein wrote that “the way to solve the problem you see in life is to live in a way that will make what is problematic disappear”. It’s a good idea, but Wittgenstein clearly chose the wrong way to live. Clearly? Wittgenstein achieved a great deal, his work revolutionised philosophy, and on his deathbed he was able to request that his friends be told he’d “had a wonderful life”. Alas, his life rather epitomises that dreadful, unbridgeable divide between happiness and achievement. The best happiness demands limited goals, while the greatest goals demand the sacrifice of (at least) part of our happiness. We may read Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius and say that Wittgenstein really just needed some good meds and some CBT for his OCD and other problems, but somehow that doesn’t sound quite right to me.

Would he have been able to work so well if he did not have this way of life, this drive? Wittgenstein was a genius – he had a self-appointed duty to destroy himself in the quest for a better way of philosophising. What is important is that Wittgenstein could squeeze more philosophy out of himself. Can we, depressed perfectionists, really hope to achieve that much more by destroying ourselves, or should we just cut our losses and be sensible, care about ourselves and the world, and eventually find that thing that others talk so lovingly about – happiness?

I don’t know.