I am now at that point of my life where I and my friends have mostly all finished university and are now settling into whichever stream will carry us to our retirement. Unsurprisingly, most people are working in The City, whether as lawyers or bankers or some other nebulous financial profession. A few braver and probably more admirable souls are pursuing careers in academia. And others are merely flailing about, looking for something solid to hold on to. It is true to say that we have not graduated at a particularly good time.

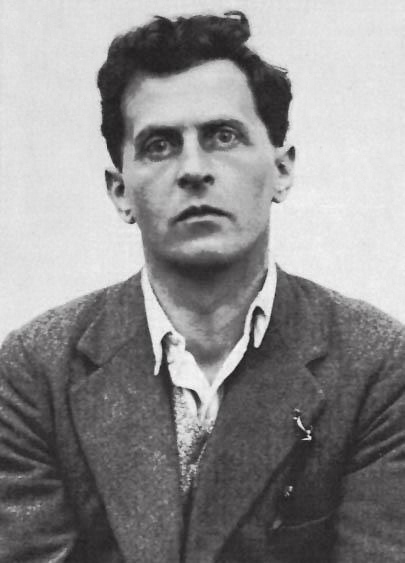

Of all my friends, however, it is Sophie for whom I have the most respect. She decided to work on a vineyard in Burgundy rather than engage in any kind of rat-race. Hard, physical labour, an outdoor environment – she knew, as Wittgenstein did, that these are often the surest paths towards a happy, long, and restful sleep. She went against pressures, social and otherwise, in pursuing this, and in doing so rather showed the rest of us up by demonstrating that whatever one’s educational background, however well-bred one is, still the ultimate barrier to us working in a similar field is only our own cowardice.

I was visiting Sophie last week, just before the year’s grape picking began. That was the plan, at any rate. But the start of the harvest is unpredictable, and in the week before I arrived, I learned, rather concerningly, that instead of spending three days relaxing with an old friend, I would have to be on the fields with her, toiling away. Well, I thought, at least it will be an experience. And indeed it was.

Prejudices

Though I grew up on a farm, I never really participated in its operations, and though I live in the countryside now, I still look on those who live from the land with uncomprehending admiration. Like most people without experience of actual farm labour, I had a somewhat idealised view of things. Rather than rely on what little I remembered from our hard life in Scotland, my main inspiration was Tolstoy’s Levin, out on the fields in Anna Karenina. I believed that work outside is tough but rewarding, an opportunity to fall into a community where everyone looks out for everyone else, and that on the fields God lurks underneath each unturned stone. At the same time, however, I retained a certain cynicism. I thought that farmers were boring and bigoted, and that I was probably wrong to like the idea of the work. In short, I believed while constantly doubting what I believed.

What was surprising was that my suspicions, or rather my hopes, about the work, were far closer to reality than my cynicism was.

People

The farm we were working on was only about ten hectares, or twenty-five acres, and it was family run. Unlike other vineyards, or indeed most fruit picking jobs (as I understand it), the work here was rather light. Many of the pickers were regulars, people who came year after year. So long as the work was done, the pace was not overly important. We had a long lunch break each day, and a good number of rests during the day too. Although we were bussed about in vans, there was little else to connect us with the horror stories one reads of about migrant fruit pickers.

There were about twenty-five of us to begin with, and that number grew slightly once the weekend came around. I was the only Englishman; there were about seven or eight Poles; the rest were all French, though not necessarily from Burgundy. Except for the Poles, who spoke English, everyone else spoke French. For me, someone who hasn’t studied French in about seven years, and who has never really spoken the language, having to speak French was something I really should have anticipated. What I could not have predicted, however, was how easily I found myself speaking it.

Everyone knows the stereotype of the English or American abroad who refuses even to attempt to speak the local language. The French with me certainly knew it. It was partly because of that that I found it so easy to speak – I knew that even trying would stand me in good stead. And then, I think, and just as important, there was the matter of perfectionism. Precisely because I was out of practice, precisely because I had not studied French at university, I did not give a damn how I sounded – I just wanted to speak. And so my words were wrong, my speech a bizarre blend of French and English and occasionally any other available language too, and to top it all off, I apparently spoke with a Russian accent. But I was speaking, and as the days went by, I was speaking more and more, complex sentences even. The words were coming back to me, dug up from whatever deep recesses of my mind that they had hidden themselves. I even managed to learn a few new words too.

I would not have had so much success with the French if the people there were not so friendly. Almost without exception everyone was willing to talk to me, in one or multiple languages. And I met a random, but loveable, bunch of people. One man, in his fifties, with a sailor’s faded tattoos, a squashed nose, and a cigarette permanently poking out of his mouth, seemed unable to pick without removing his shirt, revealing a gigantic belly that rolled over the top of his disarmingly short shorts. A young guy in his late teens, who had previously been an apprentice at the vineyard, wore a different pair of football tracksuits each day, could not speak any English whatsoever, but got incredibly excited every time I said the word “whisky” for him. He would come up to me, ramble away in French for a minute, enjoying the look of dismay on my face, and then start to laugh. His good nature was infectious. I felt rather better when one of the other Frenchmen told me that this fellow spoke with the local dialect and that none of them understood most of what he said either.

Each lunch we were served by an enormous woman who had turned herself into such a wobbler that she could only walk with the aid of a stick – she was aided in her cooking by an equally large husband. The food they produced, however, was always filling, and delivered in generous helpings. I met a Bhutanese-Frenchman who had trained as a monk and seemed to spend all day drinking, and lots of pleasant young Poles, picking just because it was a bit of fun. The only person who ever bothered me was a mister T, the tractor driver, who was about my age. On my first day I looked up to see the Frenchman storming down my row towards me, shouting and gesticulating wildly in his finest French. I thought perhaps I had left something down by the tractor, but it turned out – after everyone else had stopped picking and several volunteer translators had jumped to my aid – that I had been picking particularly awfully, and that mister T (whose role had nothing to do with this) was very displeased. When he had finished berating me, he noticed that the rest of the field was glaring at him, and he backed down somewhat. Unsurprisingly, after that he did not bother me further. And for my part I tried to pick a little better.

Property

Perhaps the people who I liked best were the owners of the vineyard. The boss, P-, was only twenty-nine, and he still shared some responsibilities with his father. The vineyard is run very much as a family affair. Without teamwork, the whole thing would fall apart. This is because of French inheritance law, which is among the strictest I have come across. Nobody can be disinherited, and property must be equally divided among the children. In practice, this means that France has a high rate of inheritance-related murders. It also means that major wine-producers, including major champagne brands like Taittinger, have suffered due to the enforced division of their lands. This vineyard has already been divided by a generation or two, and that means that some of the land belongs to people who don’t work there or have any real connection to the place – instead they simply rent it back to their family, as generously or stingily as they wish.

P, his father, his uncle, his sister, and his girlfriend – these were the family. Responsibilities are divided and so far, order and financial stability has been preserved. How many more generations it can last, however, is hard to say.

P himself was an interesting character, though I did not speak to him much. He is well-educated, tall, bespectacled, and was always trudging around in shorts and big brown wellington boots. There is something of a low-budget Harry Potter cosplay about him. But what is most striking is how out of place he is here, with his reading and his interests. He is quiet, bashful even, and slow to express an opinion. Whether he is a good leader is not my place to say, but certainly he is an atypical vineyard boss. I would like to write a story about him, one of those classical tales of one being forced, not entirely against one’s will, into fulfilling a duty that nevertheless takes one away from the place where one would really be able to flourish. P’s girlfriend was also lovely, an extraordinarily friendly woman who was an artist and seemed to carry the sun around in her chest. While we were picking she would always be suggesting silly games to play, like naming every writer beginning with each letter of the alphabet, and such like. Whenever P was with her, suddenly his reservations disappeared, and he too seemed to shine with a kind of light. He smiled, he played, he ran about with their dogs. There is a story there.

Picking

Each morning I woke up at sixish, and we started work on the fields at seven thirty. Grape picking can be automated, but currently the robots aren’t quite so good as the people. We are able to better identify things like rot and unripe grapes while we are picking, but it’s hard to say how long we’ll hold onto our advantage. It almost doesn’t matter, anyway, because fewer and fewer young people are getting involved with their local vineyards, and this means that automation will become a necessity in a few years, whatever happens with the technology.

The process of grape picking is simple. You are given some secateurs and told to gather your grapes in a bucket. People with large backpack-buckets go up and down collecting the contents of your bucket, once it’s filled, and take the grapes to the tractor, where they will be sorted a second time, and taken back to base. You can cut your grapes in different ways. If you have good core strength you can squat at each vine, or else you can kneel – the Poles all came with knee protection, as if they were actually going roller-skating. Finally, if you are lazy like me, you can sit on the ground, and slide crablike down your row. This is very slow, but less painful. And given work only ends at five-thirty, it’s best to avoid what pain you can.

We were cutting red grapes, at least while I was there. These grapes are easier to spot than white grapes, but they can still pose a challenge. You sometimes have to tear down masses of leaves to get to the grapes, giving the whole thing a rather adventurous feel, as though you are actually travelling through the Amazon jungle, but it means that it’s easy to miss a bunch or two. Sometimes the vines are diseased or have something else wrong with them and their leaves turn red, which makes it much harder to find the grapes underneath.

The grapes themselves can have issues too. Ideally, they are slightly glassy, translucent, like marbles. But when only half-ripe they can be almost matte, and a deep bluey-red. This year was not a good year for the harvest. We had to pick many bunches that were not wholly ready. And those that we picked also had major issues with rot, so that after picking each bunch we often had to stand there scraping the puffs of white dust out from the centre of the grapes. This took as much time as the picking, sometimes more. But if too much rot gets into the vats, the resultant wine can have its taste completely spoilt.

I was a slow worker. Except for one of the Polish girls, for whom it was also the first time, I was the slowest. But I did my best to make up for it by being diligent. It was a strange experience, working in a family business like this. I knew exactly who I was working for, and this made me redouble my efforts even when my strength was flagging. I wanted these people to succeed. I remember the despair in P’s uncle’s eyes as he sat there, sorting the rotten grapes. They could all see that everything was going wrong, and I didn’t want to make it any worse for them.

On the final day, it was raining. Heavily. We went out onto the fields late and returned after only an hour. It was hellish in the rain. I do not think that a comparison to the battlefields of the First World War is entirely out of the question, to the fields of mud of the Somme. My boots were caked in a toecap of mud. My clothes were wet and sticky with the stuff. In the darkness and the rain the grapes were almost impossible to make out. They seemed to live a kind of ghostly, phantom existence, forever hiding just out of reach behind another clump of leaves. My basket accumulated bunches incredibly slowly. A general hopelessness ruled the day. And though I was wearing a raincoat, it felt as if the rain was seeping through it into my bones. We all worked slowly then. And I was very glad when it was over.

Pride

Grape picking is generally not done in the rain because it is inefficient and ineffective. The other two days I worked the sun had shone and everything was golden. And it is those days that I will remember best, for those days are the days that I worked properly. However much he was an idiot for idolising peasants, I do not think that Tolstoy was wrong for valuing physical labour like this. For a couple of days I went to bed exhausted and slept well. My body ached, but in a good way – as though it were thanking me for using it the way it was supposed to be used after so long spent sitting in chairs and walking around cities. I felt part of a collective, I felt welcomed, I spoke French. These are all extraordinary things. I am sure that if I had stayed longer my body would have collapsed and I would have ended up sitting in the middle of a row, my bucket on my head, in tears. But I would not blame the work for that. I would only blame myself for not starting to work sooner.

Labouring alongside others draws us closer to them. Language proved no barrier, nor did education, nor class, nor anything else. I came across a common humanity, one that we always suspect the existence of, but don’t always see. I came across real work too – work in which one feels a relinquishing of the self, and even some of that magic force which takes hold of Levin while he’s out on the fields. While I was working I thought a lot about a particular quote of Whitman’s, one that to me reflects the reality of work as I experienced it:

Blacksmiths with grimed and hairy chests environ the anvil,

Each has his main-sledge, they are all out, there is a great heat in the fire.

From the cinder-strew’d threshold I follow their movements,

The lithe sheer of their waists plays even with their massive arms,

Overhand the hammers swing, overhand so slow, overhand so sure,

They do not hasten, each man hits in his place.

Walt Whitman, from Song of Myself section 12

Each man hits his place. I was dreadfully slow with my picking. But I was there; I took part; I felt a part of something greater than myself, and something valuable too. The pain I felt on falling asleep and on waking, the aches and sores – these I will forget. But the pride of working will go with me forever. I certainly do not think that we need to work on the fields every day of our lives. Life is not so simple as that. But spending a week or two of each year out there, working, sweating, burning – after having a taste of it, I cannot find anything to say against it. This is real life.

And next year, if my silly office job allows me to take the time off, I will experience it again.