Whether or not we ultimately see the French Revolution as stemming from a disillusionment with the monarchy, bourgeois self-assertion, or hungry peasants, it is obvious enough that after the initial turmoil the leaders who came to share power and chop heads were motivated by ideas of what society should look like, and where it was heading. The Russian Revolution and the early Soviet Union too, for all their betrayals of pure Marxian and Marxist thought, nevertheless contained many actors who took their cues from ideology, and often added their own lines to the drama. Thinkers, both on the right and the left, have been driven by ideas, consciously or unconsciously. And passionately held belief is something that many of us admire and envy, whatever the belief’s content. It is one of the attractions of the fictions of Dostoevsky that his characters believe so passionately in ideas.

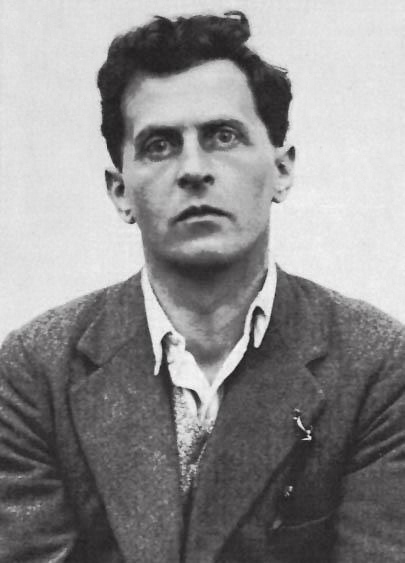

Isaiah Berlin is a historian of ideas, but to my mind his closest affinity is to the Russian novelists of the 19th century, including his favourite Turgenev, and not to other historians. Berlin’s work is filled with a serious and excited engagement with ideas, good and bad, hopeful and hateful, so that we ourselves become aware of the sheer force which animates them as well as if we had seen someone slaughtering a pawnbroker with an axe over them or dissecting frogs. This is perhaps no surprise. Born in Riga in the Russian Empire in 1909, Berlin and his family moved to Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) just in time to witness the Russian capital be torn apart, repeatedly, by revolutions coloured by ideological thought. He moved to the United Kingdom with his family shortly thereafter, studied at Oxford, and became one of the greatest thinkers of his time.

The Crooked Timber of Humanity, subtitled “Chapters in the History of Ideas”, is a collection of Berlin’s essays in which his principle concerns are on full display – the Enlightenment and Romanticism and both of their troubled legacies, and his own idea of “value pluralism”. At the centre of the collection is a magnificent, awe-inspiring essay on the Savoyard reactionary Joseph de Maistre. Besides de Maistre, other recurring figures in this collection include Kant, Herder, Machiavelli, Vico, Rousseau and Voltaire. Many of these thinkers will be familiar to us, at least in passing, but Berlin’s great strength – and the reason I adore him so much – is his ability to make their concerns appear fresh and relevant to our own age. In short, he makes us understand ideas from the inside – their excitement and their pleasure.

Rather than explore each of the essays in turn, here I will explore thoughts he develops throughout them, and why it’s exciting.

The Enlightenment Vision of the World and its Problems

These days the Enlightenment, the period in the late 17th and 18th centuries when clever philosophers, predominantly from France, tried to solve all human problems using reason, now has something of a bad name. Firstly, these eminently reasonable men (and they were, pretty much, all men), were often hypocrites. Kant, as is well known now, failed to apply his philosophy to the savages of the world, and was rather racist; Hume was no better. To my mind this charge, which Berlin does not bother addressing, is far less important than the one that out of their thought came the totalitarian systems of the earth. This is the view which Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer wrote about in Dialectic of Enlightenment. Karl Popper, another influential mid-20th thinker, called Plato, with the regimented society and clear social stratification of The Republic, one of the first totalitarian thinkers, and also had little love for the Enlightenment.

It is this view of the Enlightenment as a less-than-benign force that Berlin engages with. In The Crooked Timber of Humanity Berlin is keen to moderate criticism of both the Enlightenment and the Romanticism which followed. He explores how a combination of Enlightenment and Romantic ideas created the groundwork for modern totalitarianism, but need not necessarily lead to it.

Lost Unities – The Decline of Universalism

The Enlightenment was the last period of the world where dreaming of a utopia was in some way possible. It was an old idea that all genuine questions – about our place and goals upon the earth – could have only one valid answer. These answers could be found if we looked hard enough and knew how to do so. Finally, people believed that all the answers were compatible. People answered questions differently, whether due to religious or political thoughts, but nevertheless they were mistaken and simply missing the one Truth which could be found and should be propagated by those who found it. Believing all this makes a utopia – a place of stasis and conformity, possible. It allows for Hegel’s idea of progress, Marx’s idea of communism. It also allows for the rationalism of the French philosophes whose ideas came to justify the terrors of revolutionary France.

Killing people is of course a shame, but when you are building a perfect state, sometimes murder is necessary.

Enlightenment Smashers – Vico, Machiavelli, Herder

Berlin credits different thinkers with destroying these ideas and making way of Romanticism. Machiavelli realised that Classical and modern Christian societies had incompatible ideals. He showed that the honour and violence of Ancient Greece and Rome could not be combined with Christian ideals of meekness and piety. Both places, in short, had different ideas of perfection. Vico, meanwhile, who is something of a hero in The Crooked Timber of Humanity, understood that every culture has its own vision of reality, with its own value systems. He saw that through imagination – fantasia – it is possible for us to enter into another society’s view of the world, without adopting it as our own. Finally, Herder showed that each culture has its own centre of gravity, and would only suffer from taking its inspiration from others. Together these thinkers broke down the idea of universal Truth that had driven the French philosophes.

German Romanticism and its Legacy

In doing so, they opened up a space for German Romanticism, which was far more intellectual and philosophical than its English equivalent (both made for good poetry, tho). The Romantics focused on a cult of self, rather than the universal. In doing so they made utopias impossible, by encouraging us to see that we each have our own utopia, rather than sharing a common one. Rather than feeling and emotion, what the later Romantics were interested in was the idea of will. We each have our own inner ideal within us, and rather than make peace with the world we must do whatever we can to bring that inner ideal out into the open. The idea of being true to yourself was essentially born at this time.

At first, being true to yourself just meant being a starving artist in an attic. But it left the possibility open of a kind of solipsism, wherein your own vision of the world could grow so powerful that it denied the significance of other people. At this point one was no longer an artist of the pen, but an artist of man, shaping others to create one’s own world. It is this idea – of the disregard for others, of the sense that objective truth is impossible and violence the inevitable consequence of clashing ideas – that Berlin considers the most terrible legacy of Romanticism. It allowed for madmen to take Enlightenment ideas and ignore all criticism, creating rationalist monsters in the early Soviet Union, and terror in fascist Germany.

Neither the Enlightenment nor Romanticism need necessarily lead to totalitarian violence. Berlin, whose whole life consisted of a passionate and earnest engagement with these ideas, naturally was not willing to dismiss them completely. Instead, he makes it clear how Romanticism in particular also leaves open the possibility of humanism: “The maker of values is man himself, and may therefore not be slaughtered in the name of anything higher than himself, for there is nothing higher.” Abstract ideas have no value in themselves, and the worst thing is to get in the way of another’s will – out of such thoughts grew existentialism, a much more positive set of thoughts than those of either Adolf or Joseph.

Value Pluralism vs Relativism

Berlin’s main contribution to thought – he did not consider himself a philosopher – was the idea of value pluralism, which he built out of the ideas of Vico and Herder about the differences between cultures. Pluralism Berlin describes as “the conception that there are many different ends that men may seek and still be fully rational, fully men, capable of understanding each other and sympathising and deriving light from each other.” For example, those who value liberty above all else, and those who value equality above all else, will discover sooner or later that they cannot have a perfectly liberal and equal society – in other words, that their ultimate ideals are incompatible with each other, even though they are both recognisably good, and recognisably “rational”.

We can understand other cultures thanks to the imagination, or Vico’s fantasia, but we do not have to like them. As Berlin put it in one of the pieces included in the appendix to The Crooked Timber of Humanity, “I must be able to imagine myself in a situation in which I could myself pursue [their ideals], even though they may in fact repel me.” Literature, at its best, is in some way the proof of pluralism – we learn to see other ideals by their own internal light, even though we do not necessarily change our own views as a result.

How is this different to relativism? Berlin defines relativism as “a doctrine according to which the judgement of a man or a group, since it is the expression or statement of a taste, or emotional attitude or outlook, is simply what it is, with no objective correlate which determines its truth or falsehood.” In other words, relativism means that other cultures are unquestionable – we have no choice about whether we accept them or not, because there is too much distance suggested between our own values and those of the other group. Another way of looking at this is to suggest that with relativism, we may understand the values of other societies, but we cannot understand why they would be held. There is an insurmountable barrier between us and others, one that ultimately makes deprives us of a feeling of common humanity.

The Bad Guy: Joseph De Maistre

The majority of the pieces in The Crooked Timber of Humanity explore the ways that value pluralism works and the legacy of the Enlightenment and Romanticism; but by far the longest piece, on the Savoyard reactionary thinker Joseph de Maistre, is much more focused. Berlin’s goal here is to revaluate this thinker, dismissed by earlier historians as a simple conservative. Instead, Berlin argues that de Maistre speaks decidedly to our own time, as a prophet whose ideas in many ways suggest those of fascism. In other words, “Maistre may have spoken the language of the past, but the content of what he had to say presaged the future.”

De Maistre was for most of his life a diplomat for the Savoyard king, and his most productive years were while he was in Saint Petersburg during the age of Napoleon. He was popular in Russia, and Tolstoy even mentions him in War and Peace. His ideas were reactionary, rather than conservative. Where the likes of Burke tried to explain conservatism through appeals to sunlit uplands, peace and prosperity, Maistre’s approach was almost the opposite – he saw humanity as irredeemable, a creature that needed the violence of the executioner to keep it in check. Reaction, for de Maistre, was about saving humanity, rather than about protecting some historic ideal of playing cricket on the village green.

In practice, this meant doing everything he could against Reason and its followers. He protected irrationalism, kings and queens, by suggesting that only what is irrational can lie beyond question. Indeed, to begin questioning is already to fall foul of the Enlightenment – one must never question. He hated intellectuals, he hated the free traffic of ideas, he thought that suffering was the key to salvation, and that only a strong state and strong elites can keep our evil urges in check. De Maistre is quoted a few times by Berlin, and he comes across as the most extraordinary thinker – I feel a shiver go down my spine just reading even the shortest of excerpts. He is frightening, like Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor is frightening, because he has beliefs that he believes with all his heart and yet which to most people are complete anathema.

Here’s a taste:

“Over all these numerous races of animals man is placed, and his destructive hand spares nothing that lives. He kills to obtain food, he kills to clothe himself, he kills to adorn himself, he kills to attack, he kills to defend himself, he kills to instruct himself, he kills to amuse himself, he kills to kill. Proud and terrible king, he wants everything, and nothing resists him.”

“Don’t you hear the earth shouting its demand for blood? The blood of animals is not enough, nor even the blood of guilty men spilt by the sword of the laws.”

“In this way, from mite to man, the great law of the violent destruction of living creatures is ceaselessly fulfilled. The whole earth, perpetually steeped in blood, is nothing but a vast altar on which all living things must be sacrificed without end, without measure, without pause, until the consummation of things, until evil is extinct, until the death of death.”

All this makes one giddy. It is so violent, so horrible, and yet it fills one with a kind of awe. For Berlin, de Maistre is one of the history of ideas’ great villains, but he is a player in the drama. And we can all learn something from him. He believed that we do not know what we truly want, that ideas are often disappointing, and that the urge for self-sacrifice, for self-immolation, is just as strong as the desire for shelter or food or warmth. This is not the man of the French philosophes, but then again, as de Maistre says, “as for man, I declare that I have never met him in my life; if he exists, he is unknown to me.”

However much we may wish for ourselves, on the whole, to be rational beings, de Maistre offers a necessary dose of reality, and even if his suggestions of our terrible fallenness and the need for God and authority go far beyond what most of us like or want, still he has value. Otherwise we may end up just as foolish, just as idealistic, and just as dangerous as the Enlightenment, for all its light, turned out to be.

Conclusion

Berlin is exciting because he makes ideas feel real. He can transform a little Savoyard reactionary into a frightening, exhilarating, monster of a thinker, and he can do this with every thinker in the book. This is not because he tells us little titbits from their lives, but because he builds their ideas into something that we must engage with and evaluate for ourselves. Where do we stand on matters of the Enlightenment or Romanticism? However much we may think that they are ancient history, Berlin shows in The Crooked Timber of Humanity that their debates continue to be played out in our own era.

More importantly, in his idea of value pluralism, he advocates for a way of looking at the world which is moderate without losing the ability to judge. We can see what is good and bad in our opponents, without establishing such a distance between us and them as to make dialogue impossible. In our own age, when dialogue feels increasingly pointless, and actors increasingly hidden within the shroud of their own bad faith, Berlin provides a message of cautious hope, a guide to how to approach politics, and one that is hard not to like.

I have also read Berlin’s Russian Thinkers, available as Penguin Classic, and that is another work that I would recommend heartily. Berlin turns various thinkers, most of whom we would never have heard of otherwise, into living, breathing, arguing human beings. For anyone interested in 19th century Russian literature or history, the book is a must-read. As for this one, it’s pretty good too. Read it, think on it.