This is the real deal: Butcher’s Crossing, a Western by the author of Stoner, is a truly awesome book. Because although it’s deadly serious, it’s also a Western through and through. Adventure, violence, and the great outdoors are all here in abundance and lovingly described. The only difference between Butcher’s Crossing and more traditional examples of the genre is that Williams, through respect for it and its worlds – he himself grew up in Texas – shows that behind its clichés there lurks an untapped dread, horror, and depth. Just as Conrad cut incisively into the myths of Western Imperialism in works like Heart of Darkness, here Williams does the same for legends of America’s westward expansion. But instead of resorting to the fantastic brutality of Cormac McCarthy in Blood Meridian, Butcher’s Crossing works by being completely realistic. Its enemies are not superhuman judges but simple nature, harsh and incomprehensible.

A Hero and his Search

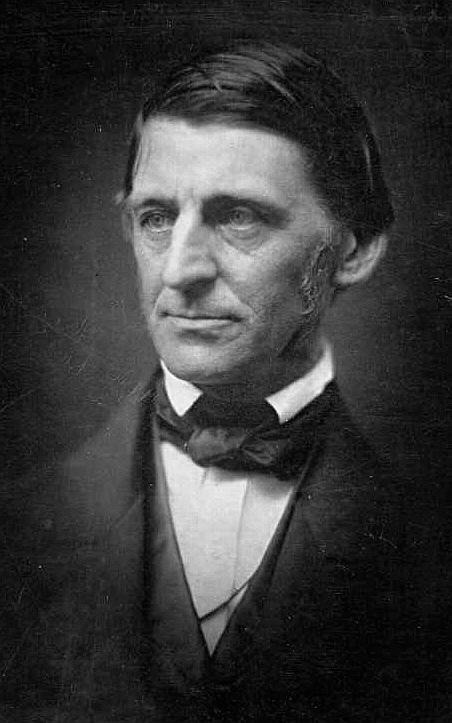

Our hero is William Andrews. A young man of twenty-three, he has done a few years at Harvard and had enough. Inspired by the lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Butcher’s Crossing takes place around 1872), Andrews sets out West, to find… something. “It was a freedom and a goodness, a hope and a vigor that he perceived to underlie all the familiar things of his life, which were not free or good or hopeful or vigorous”. But the word “perceived” already clues us into Andrew’s uncertainty. We have no reason to doubt the goodness of his intentions, but every reason to doubt his surety in what they are. At the beginning of the novel Andrews blunders into Butcher’s Crossing, a small town dependent on the trade in buffalo hides. He has a letter of recommendation for a man there, McDonald, who knew his father.

Andrews is not heroic. He is terribly naïve and idealistic. He mistakenly identifies a local prostitute as the friend of a man he’s meeting in the saloon, rejects an offer of work from McDonald (“I don’t want to be tied down”) and almost immediately gets involved with a huntsman, Miller. This man tells him a story about a mythical, heavenly valley in Colorado Territory filled with buffalo, and Andrews can’t resist offering to help finance an expedition there. He’s attracted by Miller, a man of action who knows the land, and who seems to understand what Andrews is after. “A body’s got to speak up for his self, once in a while”, he says. Three men join Andrews on the expedition: a religious one-armed drunkard, Charley Howe; a coldly independent German, Fred Schneider; and Miller himself. For Andrews, this is the most meaningful time of his life.

But perhaps that meaning’s not what we’re really after.

Adventure and Style in Butcher’s Crossing

What does the feeling of adventure mean, and how do stories give us it? Perhaps it is feeling of seeing something new when it is balanced by the sense that this new thing is real and valuable. When we look out of the car window and see nothing except repeating suburbia, or an endless forest, it can feel like it’s not an adventure because we don’t want to find value in the landscape, though for someone with a different set of experiences, this suburbia or woodland could be exactly the novel world they are looking for. A writer of talent can make the familiar new and the unvalued valuable, but there certainly needs to be a journey involved in an adventure too. We need to feel a sense of movement, of progression in landscape or in knowledge.

The adventure of Butcher’s Crossing is a descent. I noticed that the characters of the book are almost always described as going downward in key moments. And this downward path is a moral one as well as a physical one. But long before the darkness creeps in, we are treated to a world of beauty. The world of Emerson’s “Nature” and picture books Andrews read when he was at home. And this beauty is described with a style that for me is incomparable. Williams is a master of the perfectly carved sentence, one neither too long nor too short. When you read him you have the feeling that he worked out every word and its position with the utmost care and long before he put pen to paper. An interview with his widow I read bears this out. But he is also meticulous – every action is described in detail.

“The rich buffalo grass, upon which their animals fattened even during the arduous journey, changed its colour throughout the day; in the morning, in the pinkish rays of the early sun, it was nearly gray; later, in the yellow light of the midmorning sun, it was a brilliant green; at noon it took on a bluish cast; in the afternoon, in the intensity of the sun, at a distance, the blades lost their individual character and through the green showed a distinct cast of yellow, so that when a light breeze whipped across, a living colour seemed to run through the grass, to disappear and reappear from moment to moment. In the evening after the sun had gone down, the grass took on a purplish hue as if it absorbed all the light from the sky and would not give it back.”

The Mountains: Buffalo Killing

A virgin land, the mountain valley, their goal – Miller’s suggestion that there is a secret paradise has a kind of mythic feel to it. Elsewhere, the buffalo numbers have already massively declined from overhunting. But the place is real, and soon the hunters reach it. “A quietness seemed to rise from the valley; it was the quietness, the stillness, the absolute calm of a land where no human foot had touched”. Andrews feels a sense of fulfilment as they approach the mountains, but as before this fulfilment is vague and nameless. Once more the narration refers to a “descent”. The hunters set up camp at the top of the valley, and then each day they head into it. Their aim is to slaughter and skin as many of the buffalo as they can.

The killing is mechanised and pointless. Horror is something we need to imagine for ourselves, from sounds and images, like the sea of bones Miller talks about being left behind after the buffalo have been stripped and had time to decay. Williams’ characters don’t acknowledge it themselves. The buffalo they kill are strange creatures. It can happen that they go into what is called a “stand”, where they – deprived of a leader – refuse to move, even as they watch their brethren being slaughtered all around them.

“They just stand there and let him shoot them. They don’t even run.”

This happens in Butcher’s Crossing, again and again. Instead of showcasing nature’s nobility, we find nature’s stupidity, its incomprehension. The idealised joy of the hunt – of the chase, of the feeling of man vs beast – is relentlessly undermined by the way that the buffalo just let themselves die. And Miller is obsessive. He aims to clear the entire valley, killing thousands of buffalo even though they don’t have the space for all the skins on their wagon. His urge is frightening and destructive, but none of the other characters stand in his way. Instead, they watch and help. Andrews himself has a go with his own rifle, even as he admits to himself that “on the ground, unmoving, [the buffalo] no longer had that kind of wild dignity and power that he had imputed to it only a few minutes before”.

The Mountains: Nature and Identity

What meaning can be found in this slaughter? Is this what Andrews wanted, what he needed? Butcher’s Crossing is not a book to tell us what to believe. In fact, it is brutally anti-ideological, destroying truths rather than trying to build them. Andrews, because he is searching for a meaning, is susceptible to the meaninglessness around him. Instead of filling the absent centre in his heart, the slaughter hardens it. It says that there is nothing good here, and the world is simply amoral, empty of any kind of truth. In some way, his journey reminds me of that of William in the first season of Westworld. In both cases, the person that we find in the search to find ourselves isn’t who we wanted to be at all. But by that point it’s already too late to change.

Nature cannot passively take beatings forever. At some point, arbitrarily, the tide turns on the hunters in their mountain paradise. Snow begins to fall. And what once was going to be the easiest hunt of them all quickly descends into hell. With snow, there is no way out of the valley, and the same battle for survival that the men prepared for the buffalo, now nature prepares for them. And the battle is worth waiting for, though I shan’t spoil its outcome here. The climax of the book’s second act is something to behold. It takes the Western genre and builds from them something every bit as horrific and beautiful as Blood Meridian. But here it is a thousand times more real – and for that, perhaps even more frightening.

Conclusion

I read Stoner a whole ago, but for me Butcher’s Crossing is the better book. Everything about it is awesome. The style is a model worth studying, of clean sentences and powerful images, but what really sets it apart is the story. Butcher’s Crossing is an adventure, taking those simple Western tropes that many have taken before, but unlike those predecessors Williams’ builds from them a work that is thematically dense and demands close attention. Andrews’ story of self-discovery and its dangers is one that has only become more relevant as time has passed and our culture has moved more and more towards self-creation, and the story’s fundamental lesson – that the person we find in extreme situations is not “real us” so much as only a possible version of “us” – is one that everyone can learn from.

But most of all, Butcher’s Crossing is a Western – exciting, adventurous, and fun. It’s a joy to read, and I thoroughly recommend it.

Have you read Butcher’s Crossing or anything else by Williams? What do you make of him? Leave a comment below!

Dec 2020 Update: I have now also put up a review of Augustus, Williams’ unbelievably awesome final completed novel. I think it’s even better than Butcher’s Crossing.