I watched Todd Phillips’ Joker yesterday and it may well have been the best film I’ve ever seen – but then, I’m not exactly a film person. When I watch films, I generally balance out my serious reading by choosing light-hearted movies. Joker shows an alternative path forward for the ever-popular comic book movie genre – one that says that films about costumed heroes and villains can be every bit as introspective and challenging as other “serious” films. Indeed, given the violence, destruction, and brutal origins and lives of many comic book heroes and villains, perhaps the films should be.

Joker is also a highly political film, as much of the more negative media coverage of it has indicated, but the suggestion that Joker supports the cause of “incels” is to my mind very much a misplaced one. Instead, using ambiguity as its guiding principle, Joker carefully explores the connections between class, violence, and mental illness. In this way, I’d like to use it as a companion piece to explore a few of the ideas I mentioned in connection with Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism, which I looked at here.

Medication and Meetings – Austerity in Joker

At school I ended up doing some community service. I’m pretty sure it was there only because it’s one of the things private schools in the UK need to do retain charitable status. Either way, there were various activities on offer, ranging from picking up litter to looking after our (private!) library… I, however, somehow ended up doing one of the few serious activities – I chose to help a local theatre company teach people with Down’s and autism how to act. It lasted about half a year and was a life-changing experience. Never before had I spoken to anyone with Down’s. I remember the unease I felt on first entering the school buildings they used for the training. I’d thought these people were monsters. And when I first went to the bathroom and heard one of them noisily coming in a felt a real fear come over me.

Luckily, all that passed. With time I got to know each of the people there. Not well, but enough to realise that my preconceptions of them had been completely out of touch. They were, even though they often needed help, people like the rest of us, with their own passions, loves, and sadnesses. But I mention all this for another reason. One session one of our acting tasks was to pretend we were in a political rally. Obviously, the whole idea was strange for a bunch of boys who saw nothing amiss in the current system. But the others were excited. Each and every one of them chose the same topic for their protest – cuts to their benefits, challenges in getting medication and access to counselling when they needed it. It was a humbling moment to realise that these peoples’ entire lives were actually affected by our votes and politicians.

I couldn’t, after that, consider blindly the consequences of austerity and cuts the same way. Joker likewise features relatively prominently those political-economic decisions that can cause real consequences for our mental health. The first scene in the film features Arthur Fleck, the future Joker, having a meeting with a mental health worker. Although she doesn’t much care for him, she at least tries to help by encouraging him to open up and organising his medication. But when they meet again, later on in the film, she announces that her department’s budget has been cut. She can’t help him anymore, and he loses access to his medication. The film doesn’t suggest that she is doing a good job – in fact, Arthur gets angry at her for ignoring what he says and just repeating the same questions – but it’s undeniable that he suffers when her support is removed. Politics has human victims.

Violence in Joker – Purpose and Effect

The high point of the film’s early stages and the first decisive moment in Arthur’s transformation into Joker is his killing of three young men on the subway. They are well dressed but drunk, and turn out to be employees of Wayne Enterprises. After verbally abusing a young woman they turn on Arthur and begin – randomly – beating him. However, using a gun given to him for his protection, he shoots two of them and finishes the third off as he tries to escape. The murders – as determined by the media, and by Thomas Wayne himself – are politically motivated. Such “clowns” are simply envious of the rich for being more successful than they are. Wayne’s remarks lead to a general increase in civil unrest. What was not a murder to begin with – it was self-defence – is morphed into a symbol of class conflict by Wayne’s ignorance.

Violence as a Reflection of Moral Decay

Joker is a violent movie, but its violence is brutal and infrequent rather than sustained, as in a superhero movie. It’s important, considering the criticism of the film, to note that all of the violence serves a thematic purpose. There are a few scenes I’d like to mention and explain why the violence is, in its way, necessary. The first scene, which features in the trailers of Joker, involves the theft of Arthur’s sign by a few children. After chasing them through town they eventually hit him over the head with the sign and begin kicking him while he’s on the ground. The violence is unmotivated and pointless – its purpose in the film is to show the state of moral decay into which Gotham has fallen at the film’s beginning.

In the film, Thomas Wayne enters the mayoral race with the aim of bringing prosperity back to the city. He comes at it from a standard right-wing perspective, arguing that what will work for his business is bound to bring happiness and economic rejuvenation back to the people too. I’m not an economist by any stretch, but I’m willing to say that his view is dangerously simplistic – (just as opposing views from the left can be). Wayne himself is a big fellow, the very model of a serious capitalist. He encounters Arthur once in the film, in a bathroom at a theatre, where Arthur claims he is Wayne’s son and begs for kindness – more on that later. Wayne’s reaction, however, is to punch Arthur to the ground. As soon as he realises that Arthur won’t accept his answer, he resorts to violence. A simple solution, but not the moral one.

Does Violence Have to Beget Violence?

When violence is undertaken by the representative of the status quo in Joker instead of a search for a peaceful solution it becomes clear what kind of moral decline Arthur’s world is undergoing. One of the most poignant moments, if I’m remembering right, is when Arthur declares to the talk-show host Murray Franklin that if people only showed a little human decency then he himself wouldn’t have turned out the way he was. But instead, violence often begets violence, as Arthur discovers when he learns from a trip to Arkham Asylum that as a child he was physically abused. In fact, his recurrent uncontrollable laugh turns out to be due to head trauma undergone during that time.

But it’s interesting the way that the abusive childhood trope is used in Joker. Instead of simply becoming bad because of his brutal childhood, Arthur is left damaged – with his laugh – but able to live normally and kindly. It is only the endless mocking of his laughter by other people that leads him to violence, rather than the original abuse. The responsibility for his murderous madness becomes (partly) that of those who mocked him instead of showing warmth. He could easily have turned out differently if they had. When Arthur murders one of his old colleagues, Randall, but spares another – Gary – for treating him kindly, it isn’t madness on his part so much as the only possible action given a world in which violence becomes acceptable for solving problems. It’s difficult not to look at Joker’s violence and find that Arthur’s actions are the necessary results of his surrounding world.

Capitalist Realities – Who Decides What’s Real?

I found Joker at times difficult to watch, and not just for the violence. To me it ended up echoing a world that I was all too familiar with myself, growing up in highly privileged circumstances in the UK. The challenge of Joker is that it forces us to become aware of the multiple “realities” that exist in the highly unequal societies engendered by capitalism, and the way that they are easily manipulated. The manipulation of reality by the rich that is most interesting when comparing Joker with Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism. I’ve already mentioned how Thomas Wayne, using his influence and the media, creates a reality in which the deaths of the three businessmen is as a sign of class resentment instead of self-defence or simply a mystery. This idea of jealousy comes up again and again from his mouth and that of other wealthy characters like Murray Franklin.

But what the film is equally clear about is that this idea is a lie. There is resentment against the inequality, but it is in no way from jealousy. What the film instead shows is the way that, carelessly, the rich can hurt the poor without realising it. From cuts to mental health services to Murray’s television show, where he plays a clip of Arthur’s bad stand-up to laugh at him, there is a sense that the although the rich think they understand the poor, by their actions they repeatedly deprive them of their dignity. When Arthur tells Murray that his show humiliated him for entertainment Murray’s response is that “you don’t know me”. But the evidence of Joker is enough to condemn him, just as it condemns Wayne. It reveals a disjunct between their self-perceptions and their actions that they refuse to acknowledge.

Of course, this idea of the accidental cruelty of the wealthy towards the poor out of ignorance is a simplification made inevitable by the length of the film. In the real world we are a little more lucky with our rich people, if only a little. But the point remains a valid one. Without trying to understand people through talking with them – and in doing so, respecting their dignity as individuals – we can’t avoid ignorance of our actions’ consequences, however well-intentioned we are.

Parentage

Arthur lives with his mother, Penny Fleck. There’s no sign of a father, and for most of Joker the comedian, Murray, is his surrogate father figure. His true parentage is only revealed later on, probably. Arthur opens one of the many letters that his mother writes to Wayne – she had once been employed by him, and trusts to his goodness to help an old employee out – and learns that Wayne is in fact his father. Arthur then heads to Wayne Mansion, outside of the city, where he encounters the young Bruce and a his guardian in the grounds. The guardian has a loud and violent argument with Arthur, who says he wants to see Wayne because he knows the truth.

But the guardian says that Arthur’s wrong, that there was no relationship, and that his mother was instead crazy. This is the officially accepted story, and, seeking the truth, Arthur goes to Arkham Asylum, where he steals his mother’s medical records. He learns that he was adopted and that his mother has Narcissism and various other disorders. Now there are two conflicting truths – the one that his mother possesses, and the one that the rich have determined. At this point it’s impossible to know who is right. But later on, we find a photo of Penny as a younger girl and see that it’s signed by Wayne. To my mind, this is proof that her story is the right one. Wayne used his power to have Arthur made an adopted foundling and have his mother discredited, all to protect himself. Through connections and power, Wayne’s reality comes to dominate.

Arthur’s hallucinations

An interesting point of comparison is between Arthur’s own hallucinations and the reality-shifting antics of the rich. For much of the film Arthur believes that he is dating a single mother who lives down the hallway, but as the film reaches its conclusion, we learn that he had hallucinated the whole thing. The moment of realisation is terrible. He enters her flat in complete despair and hoping for support but instead she asks the stranger to leave her house. All of this points to a sad truth – all of us are capable of creating our own realities, but only those who are given power are able to expand their realities beyond themselves. Wayne can erase his illegitimate son’s existence and make it something everyone accepts, but Arthur cannot count on even one other human heart to accept his need for comfort.

Overall, what all of this serves to do is make us ask questions about what we believe, and how far we can trust the reality of things as it’s shown to us. It’s easy to believe that the political actions of the privileged rarely have consequences, but Joker shows that for people living in a different, harsher reality, the consequences are real. But without any listening – whether it’s Arthur’s psychiatrist or Wayne himself, this gap of experience and privilege cannot be bridged, and we talk and act past each other. And so, the film ends in a violent cacophony. It may inspire some youthful would-be revolutionaries, but the final scenes really shouldn’t. The pointless violence may be a release of pent-up energies, but rioting achieves nothing and shows as little respect for the rich as the rich of Joker show to the poor.

Joker is clever enough to raise its questions while discrediting the easy answers it puts forward. It doesn’t advocate violence, but it forces us to ask whether or not we ourselves have a hand in creating a world in which violence is inevitable.

Conclusion

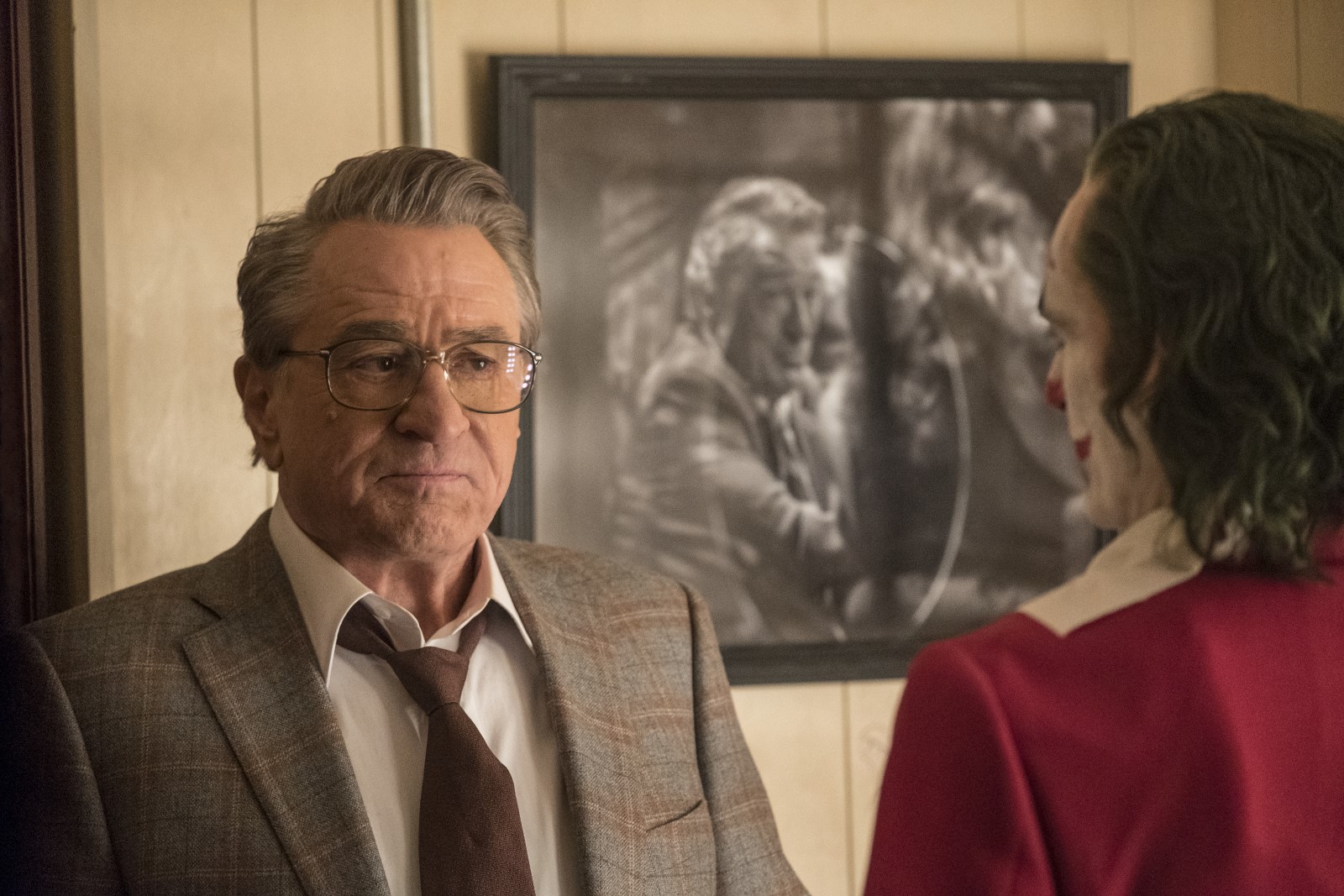

Joker is simply a fantastic film. Joaquin Phoenix and Robert De Niro give excellent performances, the music is perfect throughout – the score by Hildur Guðnadóttir takes us right into the mind of Arthur, whether we want to be there or not. It raises the questions of social inequality’s connection to mental health and violence and in doing so gets us talking about topics both taboo and rarely raised in polite discourse.

It is true that the film’s politics can, as happened with Fight Club, create its own clown-sympathisers and imitators. But I’m not sure how far we should let that turn us off the film. It’s far better to have the courage to raise the questions, even if we don’t know the answers to them, than to pretend that the problems Joker depicts – the effects of cuts to social welfare on the people who need it most, and the dreadful consequences of inequality and class conflict – don’t exist.

To devalue Joker for its politics is to do exactly the thing that Arthur warns us about in his rant to Murray when he compares killing the young businessmen to being killed himself. If Joker had only been about how being “crazy” leads you to murder then we wouldn’t be talking about it. Like a beaten madman on the street it’s easy to nod and accept such a moral and move on. But when, without excusing Arthur’s actions or suggesting that they are caused by capitalism alone, Joker shows us that our own system and its politics can exacerbate our mental illnesses and bring a man to violence – this provides a challenge to our mental status quo that we can’t just ignore in the same way.

The answer is not class violence, but – perhaps – rather a newfound sense of responsibility. We have to do our best to listen to those we’d otherwise pass over without a second glance. Otherwise, we ourselves become to blame for when they can take our neglect no longer. Ultimately that is the central message of the film – to listen and care – much more than any anti-capitalist note. And luckily, it’s a message that’s easy to accept and worth every effort to act on.

For my piece on Capitalist Realism, click here. If you’ve seen Joker and have your own view whynot leave a comment of what you thought of it and my own ideas on the film?