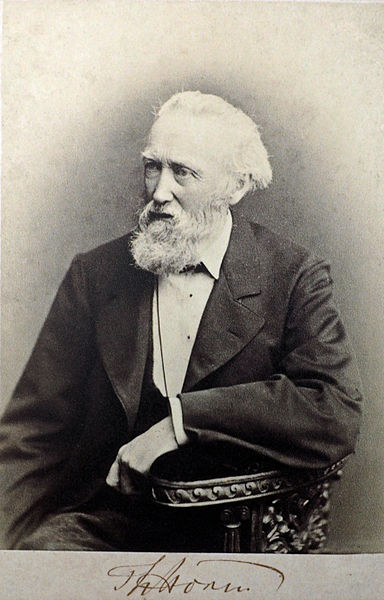

On Tangled Paths (Irrungen Wirrungen) is the fourth novel of the German author Theodor Fontane that I have read, and the third on this blog after No Way Back and Effi Briest. It is a love story, but an incredibly prosaic one. Its focus is the relationship of Lene, the adopted daughter of a washerwoman, and Botho, a young aristocrat and officer. The relationship is doomed from the start – Botho cannot possibly marry her. The great question is whether the characters will accept that and let what they have become a pleasant memory, or whether they will try to hold onto the past and potentially destroy their own futures. As with his other novels, Fontane writes simply, carefully, and intelligently about the social problems of the late 19th century. An old man when he published the novel in 1888, he treats his subject with corresponding warmth and wisdom.

Setting the Scene in On Tangled Paths

We begin with a house. Fontane demands a little initial patience – each one of his stories begins with a slow camera shot, drawing ever closer to a front door. The house in question is the one where Frau Nimptsch and Lene, her adopted daughter, live. From the beginning there is a note of plaintive nostalgia – Fontane mentions that the house is no longer there. We take this to mean that it has been consumed by the urban sprawl that transformed Berlin in the closing decades of the 19th century from a comparative backwater to a metropolis as great as any then in Europe. We are witnessing in this building something temporary as the relationships of the novel, but still we are asked to sit by, to watch, to find its beauty.

Alongside Frau Nimptsch is an old couple, the Dörrs. They grow a little produce that they sell at market. These four characters form the working class of the novel, an untraditional family of sorts. They bicker, they argue, but there is a tenderness and warmth here. We are introduced to Lene and her relationship through conversation between the two older women. Frau Dörr, whose husband married her in part because he considered her more attractive for once having had a relationship with someone from the higher classes, takes a somewhat cynical view of things – that one must remain detached. “When they start gettin’ ideas, that’s when things turn bad.” Love is not something that triumphs over all else, but one factor among many in determining what makes best sense.

Lene and her Love

Lene is perhaps my favourite heroine of Fontane’s. Though she is young, she evades many of the clichés authors, especially male authors, usually attach to their female creations. And indeed, perhaps that’s what I like about Fontane – for all his mundanity in style, his content is quietly revolutionary. I was genuinely surprised when I understood that On Tangled Paths was going to have such a focus on the lower classes. It was so natural, but at the same time unusual for a work of the 19th century. Though Lene is in love with Botho, her aristocrat, she also is intelligent enough to know that their time is limited. At one moment she’s putting a strawberry in her mouth for him to eat; in another, she’s admitting she knows this cannot last.

“Believe me, having you here now, having this time with you, that’s my happiness. I don’t worry about what the future holds. One day I’ll find you’ve flown away…”

Maybe words like these are dishonest. Maybe Lene uses them to try to convince herself to let him go. But they still speak to a deep self-knowledge and reflection, a kind of strength of character.

We meet Lene already into the relationship with Botho. They met after a boating trip went wrong and Botho intervened to save her party. That is in Easter, and before the end of the Summer things are finished between them. Time is short, and they aim to spend it well. One day, they go alone on a trip to an inn out in the countryside for a few days of peace and quiet. The whole experience is fragile, but beautiful for that very fragility. “Neither of them said anything. They mused on their happiness and wondered how much longer it would last.”

Botho…

Botho is less interesting than Lene, but then again, I’ve met far more of his kind in literature than I’ve met of hers. Botho is the kind of person I’d dismiss as a fool, no doubt because I see myself in him. He is terribly weak-willed, completely prey to external circumstances – his reputation, his family, and money. He is, at least at first, unable to do either what is necessary and part with Lene, or else to do battle against necessity and find a way for them to be together forever. Anything that suggests commitment he shies away from.

But at the same time, he is interesting more for what he and his role says about class in the early German Empire. Fontane is, after all, writing a book that is keenly attuned to slight and not-so-slight social differences. From the moment we meet him we’re aware that he’s not like the others: “He was visibly on the merry side, having come straight from imbibing a May punch, the object of a wager at his club”. He has been at the club, a place inaccessible to the women both on account of their gender and their class. He is jolly, but there is a hint of mockery about his joviality. When he declares that every station in life has its dignity, even that of a washerwoman, it’s hard to tell whether he really means it, or indeed anything he says.

…And his World

Fontane shows us Botho among Lene’s people, and then among his own. The change is immediately apparent. No longer is he Botho, but “Baron Botho von Rienäcker”. He lives in an apartment, with servants, with art on the walls and a bird in a cage for entertainment – the little hobbies of a certain social stratum. When he meets his friends they adopt masks in the form of names taken from books – Lene can read, but she hasn’t the cultural knowledge that is second nature to Botho’s coterie. He dines out with them, and we have a sense of further insurmountable linguistic barriers. Metaphors are invariably hunting related, or else concern the military – they are all officers. Botho’s enjoyment of Lene is tolerated, but not any suggestion that he would take it further. He is allowed entertainment, but not to go against his duty. He is trapped, but not like her.

But we should not judge him too harshly. He cannot truly know her life, just as she cannot truly know his. Each station has its sufferings, and while one certainly has it worse, we can only compare what we know. For Lene, the relationship is her life. “Lord, it’s such a pleasure just to have something going on. It’s often so lonely out here.” Her simple words speak to a deeper gulf. He can always find another Lene, but she can never find another Botho. Once, she describes seeing him in town among his people, riding. She cannot approach – her position is one of a spectator, doomed never to interact with him in the public space. She does not have the systematic advantage that is his by birth.

Two Perfect Matches?

Suddenly the relationship ends. Botho’s expenses have consistently eclipsed his spending, and his mother puts her foot down in a letter. Botho breaks with Lene, marries his rich cousin, and time skips forward two and a half years. Käthe, his wife, is a disappointment. Lene’s desire to learn is beautifully shown in a scene where she inspects a painting whose inscription is in English. She can mouth the letters with passionate interest, but their meaning is inevitably hidden from her. Käthe just doesn’t care. She epitomizes everything that Botho dislikes about his class – she is frivolous, full of empty words and phrases, and childish. Part of this is yet again a language problem – Botho wants authenticity; instead, he gets “chic, tournure, savoir-faire” – all French and fashionable words. He compares Käthe’s soulless letters from her time at a resort town to Lene’s misspelt but heartfelt ones.

And yet in On Tangled Paths there is no going back.

Meanwhile, Lene suffers into a new life of her own. She and Frau Nimptsch move out of their old home. In their new lodgings a religious man, Gideon Franke, falls in love with her. It is not the best match in the world, but Franke is hardworking, industrious – a new and modern man, through and through. He brings to Lene’s life much-needed stability, saving her from what no doubt would otherwise have been frightening poverty. Given a woman’s lot in the era, we should probably be as grateful as she is.

Pessimism or Realism? – the Morals of On Tangled Paths

Botho eventually comes to terms with his situation. In this lies the pessimistic, or perhaps realistic, side of On Tangled Paths and Fontane in general – no rash actions come in to save the day. But then again, no rash actions come in to spoil it. He doesn’t try to meet her again; in fact, he burns their love letters to better forget her. Lene, whose parentage is unknown, doesn’t turn out to be of royal blood. She doesn’t turn out to be anybody but herself. Botho, for his part, decides to find the good in his wife. It is not a wholly successful endeavour, but these things take a lifetime, and for Fontane it is enough to show the beginning of the process.

One day a colleague from the military meets him, Rexin, and asks his advice. He wants to know what to do about his own mistress: he hopes to marry her, or else escape Berlin altogether. He longs for “honesty, love and freedom” and hopes Botho will back him up. But Botho does not. He says that it is better to stop now, before the memories get too strong. No middle path is acceptable in the world they live in, and in the end staying within society’s bounds will always be the thing to do. It’s a surprisingly conservative message. But then, perhaps it’s the right one. The social bonds are simply too tight for anything beyond them to be worthwhile. There is no great love against the odds here, but we must remember that there is no great tragedy here either.

Perhaps “A silly young wife” really “is better than none at all”, as Botho concludes.

Conclusion

On Tangled Paths celebrates a pragmatic approach to life. Lene and Botho may not elsewhere reach the heights of bliss that they had had together, but they also remain alive and happy (enough) when the novel draws to a close. In the 19th century novel this is already a great achievement. The message that love does not, or oughtn’t, conquer all may strike us as pessimistic or overly conservative, but I find it hard to argue with here. Lene perhaps is perhaps right in her parting words to Botho: “If you’ve had a beautiful dream you should thank God for it and not complain when the dream ends and reality returns.” Better to have a beautiful dream than see life become a nightmare.

I have come to love Fontane. His novels are short, but they each display a great deal of variety in their subject matter, and they are all extremely well-written. However boring they may appear, they are all worthy of close and repeated reading. The only shame is that with On Tangled Paths I have now reached the end of Fontane’s novels easily available in English translation. There exist versions of both Jenny Treibel, and of The Stechlin, but they are hard to find. I may be forced, alas, to read him in the original again, as I did Effi. Luckily, Fontane’s worth it. Wish me luck!