Towards the end of his time writing Anna Karenina Tolstoy had something of a spiritual crisis and it almost killed him. He suddenly realised that the life he was living was pointless. Worse still, he was unable to identify any way of living that would return a sense of meaning to it. In A Confession, a short work of non-fiction published soon after the conversion, Tolstoy describes being driven nearly to suicide as a result of his despair. The only way out of his predicament except for suicide, as Tolstoy saw it, was through belief in God. The spiritual transformation that then came over him had profound implications for his work and the rest of his life. He eventually abandoned the city, lived like a peasant in the countryside, and began a career as a pamphleteer. What fiction did come this period was blunt and didactic, with rare exceptions like Hadji-Murat.

Many people would consider Tolstoy one of the greatest writers of all time, but they rarely have the late Tolstoy in mind. The late Tolstoy is a strange creature and just as strange a writer. I’m currently reading his only novel from the period, Resurrection, which partly prompts this post. The other prompt is that I’m dipping into essays by the wonderful American writer Wendell Berry, who seems to have sprung from the cradle just the same as Tolstoy eventually became. Berry is a defender of the old and simple ways, of a faith bound closely to the soil. I like Berry a lot, but something’s bothering me about his writing, just as Resurrection is bothering me, and just as other things Tolstoy wrote late in life have bothered me.

By “bothered”, I do not mean that my spirit is touched – it’s not that kind of bothering. If anything, the problem is the opposite. The problem is that I’m struggling to care. It’s all well and good to simply accuse the late Tolstoy of didacticism, but I think there’s some value in trying to go into detail to answer what exactly has gone wrong. There must be a reason why Anna Karenina and War and Peace are beloved by all, but Resurrection has failed to be resurrected from its canonical grave. In this essay I’d like to have a go working it out.

Tolstoy or Dostoevsky?

To begin with, it’s worth going back and thinking about Dostoevsky and his own fiction. Both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are world famous, but generally people prefer one or the other. I started out life as a huge fan of Dostoevsky, but now I’m in Tolstoy’s camp. What Dostoevsky does well is often called polyphony, after the name given it by the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin. By “polyphony” I mean that Dostoevsky creates a great many characters who seem to be existing independently of their author. Their views are no longer Dostoevsky’s own. But more than that, their views are so developed, and so passionately felt, that the characters seem like they cannot be the creation of Dostoevsky at all, but rather real figures, animated by belief. I cannot think of any other writer who has written people who feel so intensely as Dostoevsky’s characters do.

For a young person, these kinds of characters are well-suited to themselves. When you are young you want desperately to believe in something. Almost without exception we were all, in our youth, hopelessly idealistic. Dostoevsky provides, in a way, a buffet of ideas for us to try. But over time we come to realise that these ideas are for the most part incompatible with a good life. Suicides, murders, and despair are the keynotes of Dostoevsky’s fiction, and they are so because they are the consequences of the characters’ ideas. Those few characters who seem to find happiness are religious, like Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov, or Sonya. These characters are not particularly interesting. After all, we say, religion is for idiots.

Tolstoy’s Early and Middle Fiction

Tolstoy’s fiction before his late period is not the battleground of ideas that Dostoevsky’s is. There are characters who believe passionately, such as Levin’s radical brother in Anna Karenina, but they are few and far between. Most characters do not believe in anything, at least not actively. Anna Karenina wouldn’t say she believes in love – she just does. The same would go for Vronsky and his honour, or Dolly and her family. These people are unideological because they are all striving for one thing – a good life. Dostoevsky’s characters don’t really seem to care about happiness, and they are not striving for anything in particular. For them, the act of searching is enough. They just need some kind of outlet for the passionate feeling they have within them. The outlet’s nature, whether murder or kindness, is neither here nor there.

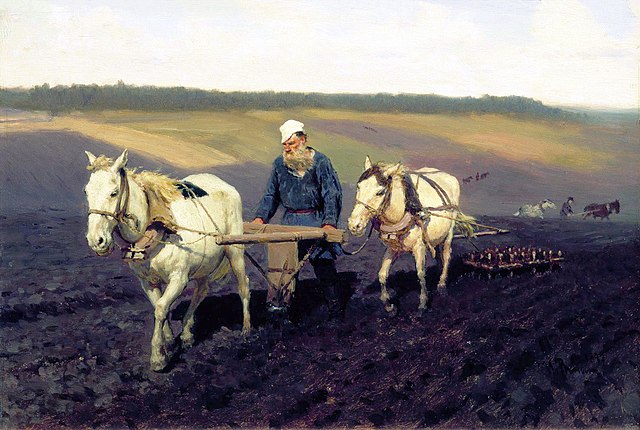

There are people in Tolstoy’s fiction who are after answers, who have that additional store of passion needed to demand a kind of seeking. They are the likes of Pierre and Andrei Bolkonsky in War and Peace, and Levin in Anna Karenina. But their crises are not the same as those of Dostoevsky’s heroes. Levin’s problem is that he is looking for an authentic and moral life. He wants to know how to live. He looks at the world of the city, where people like Stiva Oblonsky spend their days eating oysters and their nights chasing after women, and he’s disgusted. In the countryside, sitting on a haybale or cutting the wheat, he feels a kind of peace. We may call it a connection with God, but I think that that would be incorrect. What he feels is a oneness with the world, something that is more pantheistic than Christian.

Spiritual Vacuums, past and present

We can always look to Nietzsche as a great prophet of atheism, but he’s not the first by a long shot. From the Enlightenment onwards God and organised religion faced salvo upon salvo from intellectual circles, with nary any intellectually-grounded fire returned. Society was left with an absent centre, a spiritual vacuum. This was filled in many cases with radical politics. Marx called religion the “opium of the masses”, the implication being that revolutionary communism was what they really should be smoking. Nationalism also filled the void. At first that nationalism was well-intentioned, a unifying force, as it was in Italy, Germany, Greece. But in the 20th century both Marx’s teachings and nationalism morphed into horrible monsters, leaving millions and millions of dead as a result. Nietzsche, of course, proposed his own solutions to “nihilism”, but they’ve hardly filtered out and aren’t always to everyone’s taste to begin with.

So we are left today with an even greater blank than there existed back then. Nationalism nowadays is reactionary and selfish, while left wing politics can seem so focused upon marginalised groups that any utopian thinking about the greatest marginalised group of all – the working class – appears to have fallen by the wayside. More importantly, it’s not even clear if there are enough workers left to really have a revolution. Marxism has, in some sense, just fizzled out.

Our modern-day preachers, such as Jordan Peterson, attempt to fill the void for their followers. Peter Singer’s Effective Altruism attempts to provide a philosophically-sound answer to the question of what we must do, telling us that we should give away as much as we can and focus on raising the world’s happiness in utilitarian terms. Nationalism and Islamic terrorism, meanwhile, both work by preying upon those who feel dislocated from the world they inhabit. The hatred many people feel for “outsiders” is not driven by the outsiders themselves, but by the need to feel something. And anything is better than nothing. For, there are plenty among us who feel just that – nothing, or else depression and despair. For those people, the conditions of late capitalism have successfully snuffed out their hope. And hope is one of the few things capable of expanding into the space left by the spiritual void.

One Reason Why we Read Tolstoy

To people today, characters like Levin and Pierre – and their novels – are attractive because they record a search for meaning. Not for that passionate, violent meaning that dominates Dostoevsky’s works. Most of us don’t need something to die for; we just want something to live for. We want that peace and calm in our (possibly non-existent) souls. Tolstoy’s fiction, with its emphasis on the simple, rural life, is all about that quiet faith which people once-upon-a-time would have found in religion, but now they cannot get from it for any number of valid reasons. Anna Karenina’s faith is attractive because there’s nothing to believe in except that Levin’s searching is worthwhile. There’s no God at the end of it, whatever Levin seems to think. There’s simply a sense of wholeness. A good, humble life – a virtuous life – has filled the spiritual vacuum he had once had.

And when we read Anna Karenina or War and Peace, we get the sense that we too can see the gap within us filled too, if only we go out and seek the answers, and then live them when we find them.

The Late Tolstoy – The Prophet Defeats the Disciple

After Tolstoy had his conversion, he had all the answers. No longer was he content to describe the path to harmony, he wanted to force that specific harmony upon us. As time went on that harmony became ever more specific, and ever harder to stomach. A simple life became a particularly Russian peasant life. A kind of vague pantheism became a radical form of anarchic Christianity. For some people, this is to their liking. But I have spent enough time in the Russian countryside of the present day to have my own view on what the Russian peasant’s life was probably like, and it’s not exactly positive. Tolstoy’s earlier works are so effective because they see the value of searching; his later works seem only interested in the destination.

Resurrection

Take Resurrection. I am about half-way through, and I have definitely read enough to comment on it. Tolstoy’s story is not very subtle, not because he’s forgotten how to write but because didacticism, convincing us that he’s right, is now the most important thing. Take the very first sentence, in Rosemary Edmonds’ translation:

“Though men in their hundreds of thousands had tried their hardest to disfigure that little corner of the earth where they had crowded themselves together, paving the ground with stones so that nothing could grow, weeding out every blade of vegetation, filling the air with the fumes of coal and gas, cutting down the trees and driving away every beast and every bird – spring, however, was still spring, even in the town.”

This is great prose, but it is impossible to read this without feeling Tolstoy behind it. The late Tolstoy can no longer see objects without also seeing the way they fit into his moral system and feeling obliged to put them within said system. And this quickly becomes grating.

Resurrection is, from the title onwards, not exactly coy about its moral bent. A young man, Prince Nekhlyudov, finds himself on jury duty, tasked with judging for murder and theft a girl who he had once seduced. It turns out that his careless seduction, one winter’s night, of this servant girl, led to a whole string of events resulting in her presence in the courtroom some years later: she became pregnant, was kicked out, found work again and lost it, and eventually became a prostitute, her job when the murder took place. Nekhlyudov recognises his complicity in her fallen nature and determines to set things right, whatever the cost. Thus begins the process of his spiritual regeneration.

He breaks off his relations with a young lady, moves out of his house, gives away most of his land to his peasants, and is within a hundred pages far further down the path to a new life than Levin or Pierre managed to get in almost a thousand. Tolstoy is in such a rush to show us the wrongs of the world through Nekhlyudov’s refreshed eyes that he completely forgets to make Nekhlyudov truly breathe to begin with. His conversion is all too brief, and it feels cheap. In my head I can easily picture Tolstoy standing behind his hero with a whip, forcing Nekhlyudov to morally contort himself into the shape Tolstoy demands of him rather than letting things take their natural course.

But Nekhlyodov is not our only hero, for we also follow Maslova, the prostitute he wronged. She smokes; she drinks; she’s rude and rough. But when I read about her I can’t help but feel I’m basically just reading a list of things Tolstoy doesn’t approve of, things that Maslova will undoubtedly abandon once she’s been redeemed herself. Compare Maslova with Raskolnikov. Raskolnikov never feels like he’s waiting for redemption. There’s no sense of inevitability there. In a religious sense, perhaps, but not in a thematic sense, from the perspective of the story itself. Maslova, however, needs to be redeemed. Tolstoy just can’t leave her alone.

Both Maslova and Nekhlyodov feel like pawns upon the pages of Tolstoy’s novel, and their only purpose seems to be to advance Tolstoy’s views. They don’t seem to have any kind of independence, either of thought or of action. Reading the late Tolstoy doesn’t feel like a journey – it feels like being shackled and dragged along a specific path. We know where the destination is when we set out, whereas with Levin or Pierre we always have the feeling that there are other roads, other options for them to potentially take.

This lack of human freedom in Resurrection, when it’s coupled with Tolstoy’s didacticism, is exhausting. Like Karolina Pavlova in A Double Life, Tolstoy’s anger leaves Resurrection feeling unbalanced. It is too clear who is good and who is bad. Every detail, from Nekhlyudov’s golden cufflinks to Maslova’s drinking, seems to have its purpose as a criticism of the world as it lies before Tolstoy’s eyes. He can’t see anything without judging it, and the judgements are always unfavourable. In spite of Tolstoy’s determination to bring us to the good life, what actually happens is that the experience of reading Resurrection is depressing. And not because it’s a story about prisons.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich

A good comparison for Resurrection is another one of Tolstoy’s later works, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, which I reread recently. Ivan was published in 1886, ten years before Resurrection, and it shows. The novella still tries to take us towards a good life, but the methods are more subtle, and the work as a whole is more joyous.

The Death of Ivan Ilyich is first and foremost an extremely funny book. Tolstoy absolutely hates Ivan’s stupid boring vapid existence, but he understands that it’s better to dismantle it through laughter than try to annihilate it with a diatribe. Take the moment one of Ivan’s friends beholds his dead body and thinks “the only thing he was certain of was that in this situation you couldn’t go wrong if you made the sign of the cross”. Or how the first thought of people, hearing he’s died, is “a feeling of delight that he had died and they hadn’t”. In undermining the solemnity of the occasion Tolstoy has his purpose – he wants to show the citizens as selfish, unvirtuous, and themselves unprepared for death. But he does it in a way that’s a joy to read.

Where Resurrection is blunt, Ivan is full of wonderful ironies and subtleties. Things that stuck out for me included the way Ivan receives his fatal injury while decorating his drawing room – meaning that he literally dies because of the banal existence he’d been living. Another moment was when Ivan is lying there dying, and his daughter’s fiancé comes and talks about an actress with him instead of showing any kind of compassion. The novella is really funny, and yet it is perfectly capable of conveying a serious message too. In fact, the seriousness is heightened by its contrast to the levity. When Ivan tells himself at last that “death has gone”, it’s a magical moment. In Resurrection, which is entirely drab, there’s far less room for any spiritual manoeuvre.

An Evangelical is Rarely Convincing…

As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve spent some time volunteering in a prison, so I know a little about what Tolstoy describes in Resurrection from personal experience. I also once volunteered in a community project with people who had Down’s syndrome. Both of these experiences proved life-changing, but there’s a reason I don’t write about them, either fictionally or non-fictionally. That reason is, simply put, that I don’t think there’s much value in talking about them. The greatest lesson I took away from both experiences is that experience is much more important than thought. This is not something I can transfer, really, in writing. I don’t want to be like Tolstoy and tell people what to think. I have my views on rehabilitation, just as I have my views on everything else, but I have no desire to evangelise.

This a good time to think back to Dostoevsky again, who I deliberately brought up at the beginning. What happens in the fiction of late Tolstoy is something akin to what we would see in Dostoevsky’s works if they had only one fully-developed character – Tolstoy himself. Without showing the possibility of passionate alternative views, of the sort that (for example) each of the Karamazov brothers offer in their novel, Tolstoy sucks the ideological air from his late fiction, leaving only his own viewpoint. But in doing so, he sucks more than ideology from his pages – in some real sense he removes the life from his stories altogether.

Tolstoy’s “Good Life” in Practice

And Tolstoy himself, who ultimately lived what Dostoevsky simply had his characters feel, is the best argument against his own late fiction. He did not really find the good life – he just found something that eased his conscience and he tried to force it upon others. He tore his family apart through bickering and pettiness. Aside from stunts like making shoes by hand and walking to far-off monasteries, he could never bring himself to fully abandon his aristocratic position and home. He became an object of ridicule, or else of pity. And though he had his followers, I don’t think he was happy. Not in the way that Levin becomes happy, at least.

The spirit of searching, of passionate inquiry, that dominates Anna Karenina and War and Peace, is fundamentally unideological. It doesn’t tell us how to think, only to think. But once Tolstoy’s views are calcified in his old age, there’s no longer any point in us readers thinking for thinking’s sake – thinking now only has value inasmuch as it can lead us to Tolstoy’s views. And this demands not a garden of delightful ideas, but a path along an empty alley, at the end of which stand Tolstoy and his beliefs, and nothing besides.

Stories- not Authors – Change Us

I don’t think I can respect any writer who writes without a sincere desire to make the world a better place; but I also don’t think I can truly enjoy a writer who lets that desire overwhelm their stories and whatever else they might be able to say. The fire within them must be for the act of striving after answers, and not for the answers themselves.

Tolstoy’s mistake in his later fiction is that he forgets that although many people come to fiction to learn, they come to learn for themselves, and not to be told what to think. That is why, I think, the best fiction, in the sense of morally best as well as greatest, has always been didactic not in the sense of telling us what to think, but in reminding us of the value of thinking, of trying to find the answers for ourselves. The best fiction does not change us – it helps us to change ourselves. Anna Karenina, like War and Peace, shows what changing looks like. Both do little more than that, and for that we should be thankful.

Conclusion

The question “what must we do” has bothered me almost my entire life. I have looked everywhere for the answer, and though I have found many answers, including in Wendell Berry and Tolstoy, I have never found something that made me think it was worth giving up the search and stopping where I stood. The day we stop seeking is the day we stop growing; it is the day we lose our dynamism and become boring. It is a bitter irony that those searching for goodness and the good life are often better and kinder people than those who’ve stop at a certain idea of goodness and way of living, thinking they’re finished. Life itself is also much more interesting when we keep ourselves searching. Tolstoy himself, perhaps, understood this at the very end. A. N. Wilson ascribes to the dying Tolstoy the following words: “Search, also go on searching”.

Here at least, the late Tolstoy is absolutely right.